|

This is the cloudiest and windiest place on the planet,"

said oceanographer Jim Bishop, after the robotic floats were

deployed from the research vessel Revelle as part of

SOFeX, the Southern Ocean Iron Experiment. "The float

in the center of the fertilized patch just keeps sending--its

antenna is spectacular. I call it 'the little float that could.'"

SOFeX, a multi-ship project led by Moss Landing Marine Laboratory

and the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, fertilized

plankton by adding scarce iron to otherwise nutrient-rich

waters. Because phytoplankton grow using carbon dioxide, ocean

fertilization has been touted as a way to control global warming.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

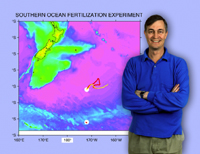

Jim Bishop and his colleagues devised

instruments that SOLOs could use to measure both organic

carbon particles, like plankton, and inorganic, like calcite,

the most common carbon mineral in seawater. The map shows

SOLO following the iron-fertilized water. |

| |

|

Berkeley Lab researchers had earlier led a collaboration

to equip SOLO floats (Sounding Oceanic Lagrangian Observers),

designed at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography to measure

temperature and salinity at various depths, with particulate

organic carbon detectors plus global positioning and fast

communications systems. Remotely programmable Carbon Explorers

were the result.

During SOFeX the Revelle, with Berkeley Lab researchers

Todd Wood, Christopher Guay, and Phoebe Lam aboard, pumped

iron into two areas along 170 degrees west longitude. In the

"howling 50s" of seagoing lore, the ocean is poor

in the silicates some phytoplankton need to form shells, so

plankton was expected to bloom sluggishly there even after

fertilization. A more vigorous bloom was expected after fertilization

of the silicate-rich waters farther south in the 60s.

The northern fertilized region promptly divided into two

patches. Revelle launched three floats, the last programmed

to stay in the center of the main patch. While the research

vessel Melville and the U.S. Coast Guard icebreaker

Polar Star later performed follow-up studies, the Carbon

Explorers operated continuously and independently, diving

and resurfacing each day to report. When high winds interfered

with communication, data were saved and played back later.

"The floats were diving to depths as great as 1,000 meters

every day, but we programmed them to 'sleep' at 100 meters

so that they would follow surface waters best," Bishop

explains. There was a risk, however: "By staying shallow

in the middle of the plankton bloom, the instruments--which

measure particulate matter by how much light is transmitted

through the water--might become fouled."

Revelle headed south to fertilize the second patch

of ocean; there the final Carbon Explorer experienced similar

storms but much-reduced satellite coverage. Heard from only

once in the next three weeks, it finally reestablished contact

and played back most of its data.

Meanwhile Bishop, using his laptop back in Berkeley, was in

daily contact with the northern floats. "Our guess at

how to program the floats to stay with the patch, plus a simple

change in configuration to reduce biofouling, paid off in

a big way," says Bishop. The two floats stayed with the

patch, one near its center, the other just outside, serving

as a control.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

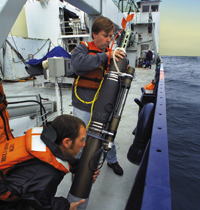

Deep-diving SOLO floats like the one

shown here have been specially equipped to report on biological

activity in the sea.

A flotilla of SOLOs faithfully tracked a plankton bloom

through the stormy Southern Ocean as part of SOFeX, an

experiment to test the "iron hypothesis," the

proposal that phytoplankton blooms can lower global temperature

by removing carbon from

the atmosphere. |

| |

|

Just before Revelle returned to the northern patch in early

February, guided by the floats' accurate GPS positions, the

skies cleared and the ship received the first color image

of the area in over three weeks from NASA's SeaWIFs satellite.

Despite expectations that growth would be poor, Bishop reported,

"we can confidently say that particulate organic carbon

in the patch has grown to be four or five times that outside

the patch."

Revelle returned to port, but the northern Carbon Explorers

kept reporting, despite days when winds exceeded 50 miles

per hour and swells averaged 40 feet from trough to peak.

By June all three northern floats had traveled over a thousand

kilometers.

The lone Carbon Explorer in the south reported periodically

until late in the Antarctic autumn, when it was overtaken

by advancing pack ice. Its data allowed glimpses of life at

1.5 degrees Celsius below zero. "That's about as cold

as the ocean can get, and now it's almost perpetually dark,"

Bishop remarked.

In mid-June, Bishop reported that after a month of repeated

"bonkings" under the ice, the indomitable Explorer

reappeared, probably surfacing through leads in the ice. It

reported its position and transmitted data stored from over

two weeks of diving in the freezing dark.

Long after all SOFeX ships had returned to port, the Carbon

Explorers were still on the job, more than half a year since

their launch. In July, 2002, Bishop reported "We still

have direct control of the Explorers, even though they are

half a world away and operating in conditions akin to those

experienced by Shackleton and his men." No other approach

to investigating the ocean's carbon budget could have matched

the performance of these intrepid robots.

The Carbon Explorers were developed with support from the

National Oceanographic Partnership Program. Their deployment

during SOFeX was supported by the Department of Energy's Office

of Science, Ocean Carbon Sequestration Program.

-- Paul Preuss

|