Three

Berkeley Lab Scientists Win Presidential Early Career Awards

From Russia with Wind

Power

Three Berkeley Lab Scientists Win Presidential Early Career Awards

Top: Margaret Torn is flanked by Office of Science Director John Marburger

and Deputy Secretary of Energy Kyle McSlarrow during the White House

awards ceremony. Second row: Michael Eisen and Kimmen Sjölander

receive their awards at the same event

Three young Berkeley Lab scientists — each named by a different government agency — received Presidential Early Career Awards for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE) for the year 2003. The winners were Michael Eisen of the Genomics Division, Kimmen Sjölander of Physical Biosciences, and Margaret Torn of Earth Sciences.

John Marburger, director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, presented the awards at a White House on Sept 9, to 57 researchers from eight agencies. He read a congratulatory letter from President George W. Bush praising the recipients for “forging new frontiers” upon a “rich history of scientific advancements.”

Michael Eisen

Eisen, an assistant professor of molecular and cell biology at UC Berkeley, was chosen by the National Institutes of Health for his work on the evolution of gene regulatory mechanisms. Remarkably conserved throughout millions of years of evolution, minor variations in gene expression have nevertheless produced the diversity of life on Earth.

Eisen’s delight in innovative experimentation is evident in the Berkeley Drosophila Transcription Network, a project he developed with colleagues in other divisions combining biochemistry, genomics, robotics, microscopy, and bioinformatics to track transcription-factor binding sites on the chromosomes of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster.

Noted for encouraging free exchange of scientific research over the internet — starting with software tools developed in his own lab — Eisen, along with Stanford molecular biologist Patrick Brown and Nobel Prize-winning oncologist Harold Varmus, last fall premiered the world’s first open-source, peer-reviewed journal, the Public Library of Science.

Of PECASE, Eisen says he values most the recognition by NIH. “It’s great that the country recognizes young scientists in this way. Scientists don’t really expect honors before the end of their lives.”

Kimmen Sjölander

Sjölander is an assistant professor of bioengineering at UC Berkeley, where she heads the Phylogenomics Group. She develops computational methods for predicting the structures and active sites of proteins and other biological macromolecules.

Sjölander studies the evolution of protein superfamilies and how these complex molecules are related by shape and sequence, using these relationships to predict the structure and function of unknown proteins. Her computational methods have enabled groundbreaking investigations into how some proteins confer disease resistance on plants, an aspect of her work involving the study of cell-surface receptors and ion channels.

She comes to Berkeley from Celera Genomics, where she was principal scientist in Celera’s protein informatics group and one of the nearly 275 authors of the sequence of the human genome first published in Science.

Sjölander’s reaction to receiving the PECASE award touched her on an emotional level, “which is not what I expected to find in science. I was thrilled that someone believed in me. The NSF is like family, and you don’t want to let them down.”

Margaret Torn

Torn, the DOE awardee, heads Berkeley Lab’s Climate Change and Carbon Management Program, coordinating the efforts of research-ers in the Earth Sciences, EETD, Engineering, and NERSC, which has led to the creation of mesoscale climate models with unprecedented fine resolution. As head of the Carbon Project for DOE’s Atmospheric Radiation Measurement Program (ARM), based at Berkeley Lab, Torn has devised a unique suite of instru-ments for gathering data at ARM’s Southern Great Plains site in Okla-homa, bridging scales from individual crops to the entire midcontinent.

In other DOE studies, she has assessed soil carbon-sequestration schemes with isotope measurements of temperate forests that have overturned assumptions about the amount of carbon pumped underground by root growth. In California, she has led state-supported studies to assess effects of global warming on wildfire danger and on threats to wildlife, agriculture, and public health.

“In an odd way it was humbling, being one of almost 60 scientists, all of whom are doing amazing things,” Torn says of PECASE. Torn particularly appreciated the DOE session preceding the White House ceremony, during which Acting Under Secretary David Garman took his theme from Thomas Jefferson, on the relationship of scientific inquiry and the free mind.

From Russia with Wind Power

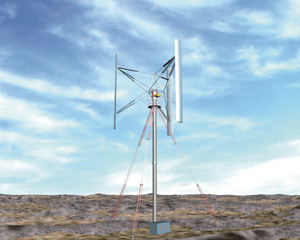

Artist’s

rendition of a 30kw wind sail turbine

Artist’s

rendition of a 30kw wind sail turbine

Next month, Berkeley Lab’s Glen Dahlbacka and Joseph Rasson will travel to a sprawling rocket-manufacturing facility located in the Ural Mountains of southern Russia. They will meet a group of engineers who have honed their prodigious skills developing submarine-launched ballistic missiles. And after passing through a gauntlet of security checks, they’ll see their latest work: small wind turbines that may someday provide electricity to the nomads of Mongolia, or the citizens of Berkeley.

This quintessential swords-to-plowshares story is the product of DOE’s Initiatives for Proliferation Prevention (IPP) Program, which fosters partnerships between national laboratories, former Soviet weapons scientists, and U.S. companies. Its goal is to diminish the chance of weapons proliferation by providing scientists with peaceful enterprises and self-sustaining employment. As director of Berkeley Lab’s IPP program, Dahlbacka oversees several such collaborations and has traveled to Russia many times. But this trip holds special promise.

“Knowing our nation’s need for renewable energy, the idea of wind turbines rang a bell with me,” says Dahlbacka of the Lab’s Technology Transfer Department. “It’s a perfect project with a genuine and growing market.”

The collaboration started last year when Berkeley Lab teamed

up with the Makeyev State Rocket Center near Miass, Russia, and Empire Magnetics of Rohnert Park, Calif, to develop vertical axis wind turbines, so-named because the blades revolve around a vertical axle, like an eggbeater. The small-scale windmills are designed to be used anywhere power lines don’t reach, such as remote ranches and villages. They can also be placed on top of buildings to supplement the existing power supply.

When Dahlbacka and Rasson travel to the State Rocket Center, they’ll inspect a three-kilowatt prototype that stands almost 30 feet tall. They’ll also inspect a smaller one-kilowatt turbine that can be easily loaded inside a car or strapped onto a horse — perfect for Mongolian nomads.

“In order to meet the Russian market, the third-world market, and the U.S. market, we had to develop something that people can set and forget,” says Dahlbacka.

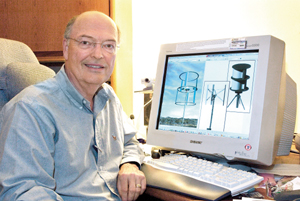

Glen

Dahlbacka with renditions of wind turbines.

Glen

Dahlbacka with renditions of wind turbines.

The prototypes mark the first-year milestone of a two-year, $1 million project funded by DOE, with about $150,000 going to Berkeley Lab and about $350,000 going to the Russian site each year. Here at the Lab, Rasson of the Engineering Division is the project manager. His team provides the collaboration with management, engineering and analysis support.

“Our role is to coordinate the project between the scientists in Russia and Empire Magnetics,” says Rasson. “We make sure that DOE’s stake in the project is met, meaning the funding is appropriated correctly and the turbines meet DOE’s expectations.”

Marketability is one such requirement. To ensure the turbines will sell, Ryan Wiser of Berkeley Lab’s Environmental Energy Technologies Division conducted a cost-benefit analysis that takes into account state incentives and performance parameters, and identifies the price targets needed for a turbine to achieve commercial success in the U.S.

Another player is Empire Magnetics, which originally approached Dahlbacka with the idea. It will provide the alternators to be used with the windmills. But the bulk of the work occurs in Russia, where 100 scientists have contributed to the turbines so far. Experts in structural design, electronics, aerodynamics, even helicopter blades, have all lent a hand. Their techniques are state of the art. To design the vertical axis airfoil, which is essentially a wing, the researchers developed a computational simulation followed by hydro and aerodynamic testing.

“This has been a world class approach, and it is one of the largest vertical axis design efforts in the world,” says Dahlbacka.

Several prototypes will be delivered to the U.S. in January for field tests. The City of Berkeley has offered its Marina as a test site, and perhaps one or two will sprout up at the Lab. Further in the future, the team hopes to build a 30-kilowatt turbine and a 100-kilowatt turbine, a design that rivals the power offered by the more conventional horizontal axis windmills that dot the Altamont Pass.

Long-term success is also an important component of the IPP program, and this means getting the technology on the international market. Business prospects already appear rosy in Russia, where the scientists have received 450 orders without advertising. Here in the U.S., three Russian scientists recently visited Berkeley Lab to showcase the windmills and help Empire Magnetics, which will introduce the turbines to the domestic market, attract investors. Ultimately, the better the turbines sell, the less likely the Russian scientists are to revert to their old trade.

“They have conducted a lot of rocket technology research, and as such they are an ideal group to provide alternative energy solutions to and engage in the international economy,” says Dahlbacka.

Chilean Dancers Draw a Crowd

|

|

|

|

Clad in colorful, traditional Chilean costumes, members of the Araucaria dance ensemble fired up the noontime lunch crowd on Friday, Aug. 28 with a performance incorporating traditional dances from the north, central, and southern regions of Chile, including Easter Island. Berkeley Lab’s own Karem Ojeda (upper right-, in white outfit), who works in the cafeteria, is part of the 14-member, 15-year-old Bay Area group.

The performance, held on the outdoor stage adjacent to the cafeteria, was sponsored by the Latino and Native American Association (LANA).

Amazon Warriors Ride Harleys to Raise Breast Cancer Awareness

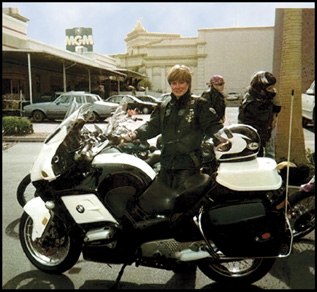

Rhonda

Witharm of the Physics Division, pictured here in Las Vegas with her

BMW bike, is one of 20 women selected to participate in the Changing

Gears breast cancer ride.

Rhonda

Witharm of the Physics Division, pictured here in Las Vegas with her

BMW bike, is one of 20 women selected to participate in the Changing

Gears breast cancer ride.

It’s not easy to bring fear or tears to Rhonda Witharm’s eyes. A former police officer for 10 years, she has seen the worst accidents, stared down gun barrels pointed at her, and brought men twice her size to their knees. But mention Sonia Mueller’s name — a young victim of breast cancer at Berkeley Lab who passed away last year — and tears roll down her face. And when she recalls some of her own experiences with this disease, her words send chills down your spine.

“It’s a scary thing to go into radiation,” she says with a steely look. “You go into this air conditioned room on a cold table and have a linear accelerator pointed at your body. They line you up, and then everybody runs for the door — except you. You have to hold still. And you do it again and again for 12 weeks.”

A technician in the Lab’s Physics Division, Witharm was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1997 — and again in 1999. Although she admits the cancer takes the wind out of her sails at times, she never let the disease rule her life. “You’re constantly worried, but you go on.”

More than just go on, Witharm is doing all she can to promote awareness of the disease and give hope to young women stricken with cancer. For that she taps into her experience as a survivor, her extensive knowledge about cancer research, and even her hobbies.

A long-time motorcycle rider, last year she took part in the Pony Express ride organized by the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. At the end of the ride, someone asked her a special favor. Could she come up and say a few words about cancer research at Berkeley Lab?

Witharm stepped up to the podium, and on the spur of the moment recalled talks by researchers such as Mina Bissell, as well as information from other scientists who reached out to her during the time of her most dire need.

“There wasn’t a dry eye there,” she says. “They had no idea all this remarkable research was going on. That’s what it’s all about: hope.”

Next month Witharm will once again embark on a week-long ride for the cause. Entitled “Changing Gears,” this is the first initiative of Amazon Heart, an organization founded this year by two breast cancer survivors from California and Australia. Witharm is one of only 20 women who were selected to participate in this ride up the California coast, from San Diego to San Francisco. Sponsored by Harley-Davidson, the ride will take place during Breast Cancer Awarness Month, the week of Oct. 2-9. The event will draw attention to the special needs of young women living with breast cancer and raise money for organizations such as Y-ME, which provides programs and services to survivors.

A rider since her college days, Witharm had given up her hobby following an accident, but was ready to take it up once again in 1997. She was eagerly awaiting the arrival of a brand new BMW bike when, two days after Christmas, she was given the devastating news: she had invasive ductal carcinoma.

“I was told, ‘You’re scheduled for surgery next week. What do you want to do?’” she recalls. “You don’t even know what you have or what your options are. You don’t have any time to decide. You go nuts.”

She considers it her personal crusade to get word out to young women that there is hope and that they are not alone.

“This is something I can do for others,” she says. “You can’t sit on your hands. The idea is to bring awareness to young women. Just because you’re young it doesn’t mean it can’t happen to you. Most of these women are in their thirties, many have children. They say, ‘I shouldn’t have it. I’m healthy. I don’t smoke, I don’t drink, I eat right — and I got it.’

“They’re very afraid, but something happens to them along this journey. They become kind of tough. They want to try some things they didn’t have the nerve to try before.”

Their spirit is what Witharm calls “an Amazon warriors’ attitude.” Greek mythology is full of tales of beautiful female warriors thundering across battlefields, battling Olympian gods, fighting hard and dying in war. Breast cancer survivors embody that spirit, embracing life with almost superhuman courage, endurance and determination. Some of them will win, some will lose the battle, but all will give it the fight of their lives.

“It’s the freedom, it’s daring, being adventuresome. That’s what happens to people when they go through something like cancer. They start embracing life instead of hanging on and going along.”

The Changing Gears ride will end in San Francisco on Saturday, Oct. 9. Welcoming the young women will be San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom. Their journey will also be chronicled on film by award winning documentary maker Melissa Regan.

Witharm also hopes these efforts will contribute toward increasing funding for cancer research like the one being conducted at Berkeley Lab. And ultimately, she says, it’s only a matter of time before a cure is found.

“It blew my mind what research they’re doing,” she says. “With more and more of this research, they’ll find a way.”

For more information on Witharm’s ride, contact her at X2246, or visit http://www.changinggears.org.

Also Supporting the Cause

Researcher Will Walk in Susan G. Komen’s Breast Cancer Walk

A recent UC Berkeley graduate and cancer researcher in the Life Sciences Division, Laura Clark is a woman on a mission. “I have pledged my life to fighting cancer,” she says. To that end she will take part next month in a three-day, 60-mile walk organized by the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. For more information, contact Laura Clark at [email protected] or see www.The3Day.org.

UC Staff Council Brings Strategy, Dialogue to Berkeley Lab and Campus

From

left to right: Rosemary Anderson (UCSC), Carla Garbis, Bill Johansen,

Ward Connerly, Director Chu, and Dave Miller (UCLA) at the CUCSA meeting.

From

left to right: Rosemary Anderson (UCSC), Carla Garbis, Bill Johansen,

Ward Connerly, Director Chu, and Dave Miller (UCLA) at the CUCSA meeting.

Two weeks ago, 31 delegates from around the University of California convened at Berkeley Lab for the first meeting of the Council of University of California Staff Assemblies (CUCSA) for this academic year.

The Council seeks to bring a staff perspective to UC policymakers, namely UC President Robert Dynes and the UC Board of Regents. It has addressed the Regents on such diverse topics as budget issues, student fee policies, capital programs, and domestic partner benefits. The 30-year-old council also serves to improve communication between the local administrations and staff, and between staff at the various UC locations. CUCSA is made up of two delegates from each UC institution and three council officers elected from among the delegates. There are about 110,000 administrative staff in the UC system.

The historic two-day meeting, which began on Sept. 2, marked the first time delegates from all 10 campuses, UCOP, and the three labs under UC management (Los Alamos, Lawrence Livermore, and Lawrence Berkeley National Labs) met together. UC Berkeley and Berkeley Lab hosted the meeting, giving the delegates a glimpse into one of the closest partnerships between a lab and campus in the UC system.

After the group’s morning tour of the ALS, Director Chu kicked off the final day of the meeting by voicing his support for CUCSA’s mission. “UC is the greatest public education institution in the world, both in terms of educating students and furthering research and education,” he said. “We are creating human capital and knowledge for the next generation. And without staff support, the researchers won’t be able to function. You are an essential ingredient in all of this.”

Dave Miller, a UCLA staff member and current CUCSA chair, thanked Director Chu for his warm welcome and expressed his appreciation for the ALS tour. “This was a fascinating experience to get to see some of the research here at the Lab,” said Miller. “It is important for those of us from campuses to get a sense of the important work happening here at the Lab.”

Bill Johansen, Berkeley Lab’s senior delegate and a member of the Life Sciences Division, further outlined CUCSA’s role. “We want to foster respect, communication, and collaboration among staff and other members of the university community,” he said “And national labs have more in common with the campuses than people think. We talk about the same topics, such as worklife issues, employee retention and recruitment.”

“We would also like to continue the dialogue here at Berkeley Lab,” added junior Berkeley Lab delegate Carla Garbis, with the Business Services Division. To do this, Johansen and Garbis hope to soon convene a series of forums in which Berkeley Lab staff learn more about CUCSA. The forums will also allow Johansen and Garbis to gather input on issues that the Council is addressing. In addition, the two delegates would like to work with Director Chu, Berkeley Lab management, other employee groups, and employees who are interested in enhancing dialogue.

The morning also saw a spirited question-and-answer session featuring Ward Connerly, a member of the UC Board of Regents and a strong supporter of appointing a staff adviser to the Regents. Because Connerly’s 12-year term expires next March, the pressure is on to bring this issue to a vote.

“With three more meetings to go before I leave, I want to work to ensure there is a strong staff representation at the table,” said Connerly. “The remaining question is how do we select one person to speak on behalf of 170,000 people.”

Connerly was quick to point out that staff representation won’t get every Regent’s nod.

“Naysayers envision a corporate model, said Connerly. “But we must convince these people that this is a different kind of institution.”

New Plan Allows You to Double Tax-Deferred Retirement Savings

Employees who wish to increase the amount of money they invest in a voluntary deferred compensation retirement plan have much to celebrate. Effective Sept. 1, 2004, a new 457(b) retirement savings plan became available to UC and Lab employees, allowing them to raise their tax-deferred contribution by up to twice the amount they can invest in the 403(b) plan alone.

A comprehensive package of information, which includes a chart comparing the features of the two plans, was mailed out to all employees last week. The Benefits Department would like to remind everyone to read the materials and remember that in order to start contributing to the new plan with the Oct. 1 paycheck, employees must enroll in the 457(b) Plan by 5 p.m. today (Sept. 17). Otherwise, enrollment is open at any time. Contribu-tion effective dates are subject to Fidelity and Berkeley Lab payroll processing deadlines.

The 457(b) Plan is administered by Fidelity Investments Tax-Exempt Services Company, which was selected by UC through a competitive bid. To enroll, employees must access the Fidelity online service at www.fidelity.com/atwork or call Fidelity Investments at 1-800-343-0860. No paper forms will be accepted.

Similar to the 403(b) Plan, the new plan offers a convenient way to save for retirement through payroll deductions. All contributions are made pre-tax, with additional taxes on earnings deferred until withdrawal. Employees can choose to participate in the 403(b), the 457(b) Plan, or both. The UC contribution limit for 2004 is $13,000 for employees under the age of 50 and $16,000 for those over 50, for a combined total of up to $26,000 and $32,000, respectively.

Participants in the 457(b) plan are charged a $45 annual fee assessed in quarterly amounts of $11.25 while they maintain a balance in the plan.

The 457 Plan allows employees to invest in any of the six UC-managed funds currently available: UC Savings Fund, UC Insurance Company Con-tract (ICC) Fund, UC Equity Fund, UC Bond Fund, UC Balanced Growth Fund, and UC Treasury Inflation-Protected (TIPS) fund.

For additional information, refer to the 457(b) Plan package mailed by Fidelity, the information found on UC’s “At Your Service” website (http://atyourservice.ucop.edu), or call Fidelity Investments at 1 (800) 343-0860.

Compact Neutron Generator Heads for Health Mission in Italy

Will be used to develop cancer treatment

With

the compact neutron generator bound for Italy are (from left) Frederic

Gicquel, who engineered the design; William Barletta, division director

of AFRD; Jani Reijonen, scientist in charge of operation; Ka-Ngo Leung,

leader of AFRD’s Plasma and Ion Source Technology Group; and

Hanna Koivunoro, a graduate student in AFRD involved in moderator

design.

With

the compact neutron generator bound for Italy are (from left) Frederic

Gicquel, who engineered the design; William Barletta, division director

of AFRD; Jani Reijonen, scientist in charge of operation; Ka-Ngo Leung,

leader of AFRD’s Plasma and Ion Source Technology Group; and

Hanna Koivunoro, a graduate student in AFRD involved in moderator

design.

Berkeley Lab’s Accelerator and Fusion Research Division (AFRD) is shipping a custom-made compact neutron generator to the Inter-national Foundation for Research in Experimental Medicine, or FIRMS, a consortium led by the University of Turin, Italy. In Italy the unique neutron generator, of a kind recently invented and developed by Ka-Ngo Leung and his colleagues in the Plasma and Ion Source Technology Group, will be used in tests to develop a treatment for brain and liver cancer based on boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT).

In BNCT, certain boron-containing compounds are injected into a patient’s bloodstream and accumulate in malignant tumor tissue. When irradiated with neutrons, some of the boron atoms capture neutrons and decay, releasing short-range radiation that, it is hoped, kills the tumor but does not damage other tissues. Thus the treatment has promise for tumors that cannot be removed in any other way, either by surgery, drugs, or other forms of radiation. BNCT has been tested since the 1950s with mixed results, using nuclear reactors or accelerators as neutron sources.

The Berkeley Lab compact neutron generator works on an entirely different principle. In the version made for FIRMS, deuterium ions — nuclei of hydrogen consisting of one proton and one neutron — hit a cylindrical, water-cooled target of titanium and copper, resulting in deuterium-deuterium reactions that release a hundred billion neutrons per second.

“Most of the beam is composed of single atoms instead of deuterium molecules,” explains AFRD’s Jani Reijonen, who describes his role as “making the generator run.” A monoatomic beam means the generator emits more neutrons having the same energy, a high power otherwise achieved only by much larger sources.

Berkeley Lab is shipping only the ion source, target, and other components of the heart of the system to Italy, an assembly measuring some 40 centimeters in diameter by 70 centimeters in length. The necessary shielding and moderators to enclose the generator will be provided by FIRMS.

Ka-Ngo Leung says, “The deuterium-deuterium design will be suitable for tests, but actual cancer treatment will eventually require more power. When the time comes, the generator can be upgraded to operate with a tritium-deuterium beam.”

FIRMS representatives approached Berkeley Lab’s Pamela Seidenman of the Tech Transfer Department after hearing Leung speak at conferences in Europe. Medicine is just one possible venue for the compact neutron generator, which has myriad potential applications in research, industry, and homeland security.

Guiding Light on the Nanoscale A Step Towards a Photonic Internet?

Optical or photonic computers, which make calculations using light rather than the electrical currents of today’s devices, are the gold medal dream of information technology. Photonic computers could solve problems in seconds that would take electronic computers months or even years to solve. A photonic Internet could transmit data thousands of times faster than today’s typical high-speed connections. For this promise to be realized, however, scientists must first find a way to manipulate and route photons with the same dexterity with which they manipulate and route electrons. Researchers with Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division (MSD) have taken an important step towards that goal.

MSD chemist Peidong Yang led a study that demonstrated that semiconductor nanoribbons — single crystals measuring tens of hundreds of microns in length but only a few hundred or less nanometers in width and thickness (about one ten-millionth of an inch) — can serve as “waveguides” for channeling and directing the movement of photons through circuitry.

“Not only have we shown that semiconductor nanoribbons can be used as low-loss and highly flexible, optical waveguides, we’ve also shown that they have the potential to be integrated within other active optical components to make photonic circuits,” says Yang, who is also a professor with UC Berkeley’s Chemistry Department.

Yang and his colleagues synthesized their nanoribbon waveguides from tin oxide, a semiconductor of keen technological interest for its exceptional potential to be used to transport both photons and electrons in nanoscale components. The single crystalline nanoribbons they produced measured about 1,500 microns in length and featured a variety of widths and thicknesses.

“Ribbons that measured between 100 to 400 nanometers in width and thickness proved to be ideal for guiding visible and ultraviolet light,” says Yang.

After attaching nanowire lasers and optical detectors to opposite ends of the tin oxide nanoribbons, Yang and his group demonstrated that light could be propagated and modulated through subwavelength optical cavities within the nanoribbons. The nanoribbons were long and strong enough to be pushed, bent and shaped with the use of a commercial micromanipulator under an optical microscope. Freestanding ribbons were also extremely flexible and could be curved through tight S-turns and twisted into a variety of shapes.

Yang says that the nanoribbon waveguides can be coupled together to create optical networks that could serve as the basis of miniaturized photonic circuitry.

The results of this study were reported in the Aug. 27, 2004 issue of Science. Co-authoring the paper with Yang were Matt Law, Donald Sirbuly, Justin Johnson, Josh Goldberger and Richard Saykally.

JGI Big Hit with Final Chromosome 5 Sequence

“It ain’t over ‘til it’s over,” said Yogi Berra, manager of the New York Mets during the 1973 baseball pennant race. The same can be said for the Human Genome Project (HGP). Two decades after being launched by the DOE and four years after the announcement of the completion of a draft human genome sequence, the HGP continues to produce big hits.

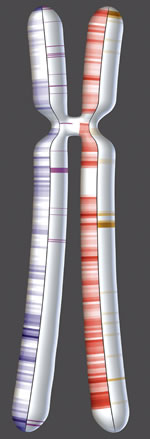

Chromosome 5, the largest human chromosome finished to date and the one that Berkeley Lab originally assumed stewardship of back in 1994, is the latest to have all its i’s dotted and t’s crossed. Its sequence analysis is featured in the Sept. 16 issue of Nature. With half of the 24 human chromosomes “in the books” and now two out of the trio of DOE chromosomes completed (5 and 19 down, 16 to go), chromosome 5 features key disease genes and a wealth of information about how humans evolved.

Chromosome 5 is made up of 180.9 million genetic letters – the As, Ts, Gs, and Cs that compose the genetic alphabet. Those letters spell out the chromosome’s 923 genes, including 66 genes that are known to be involved in human disease, including a cluster that codes for interleukins, molecules that are involved in immune signalling and maturation and are also implicated in asthma.

The spaces between the genes are as important as the genes themselves, said Eddy Rubin, JGI’s director. “In addition to genes that code for diseases such as obesity, colorectal cancer, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, there are other important genetic motifs gleaned from vast stretches of noncoding sequence.” Rubin says that comparative studies conducted by Berkeley Lab scientists have dug deep into the vast gene deserts, where it was thought there was little of value. Under closer scrutiny, these gene-free stretches, conserved across many mammals, actually have powerful regulatory influence.

Previously considered “junk DNA,” these seemingly barren regions have taken on greater prominence as researchers have learned that they can control the activity of distant genes. Some of the noncoding regions have also stayed remarkably consistent compared with those in mice or fish rather than accumulating mutations over the course of evolution.

“If you have such large human regions that stay conserved over vast evolutionary distances, it strongly supports the idea that they must contain something important,” said Jeremy Schmutz, lead author on the Nature paper who led the sequence finishing effort as informatics group leader at the Stanford Human Genome Center. Any mutation that appeared in those conserved regions was likely to have either killed the animal or made it less able to reproduce, preventing the mutation from making it to the next generation. So far, nobody has shown what role the conserved regions play. “What this says is that we don’t know as much about this conserved stuff as we think we do,” Schmutz said.

Genomics Division’s Jan-Fang Cheng was one of the early contributors to the chromosome 5 project. His group isolated the bacterial artificial chromosomes that served to cover the entire chromosome and helped to initiate the mapping and sequencing. This enabled colleagues in the Rubin Lab to shed light on the cytokine genes and their relevance to human hematologic and immunologic disorders.

JGI’s Susan Lucas led the chromosome 5 sequencing effort while Joel Martin rode shotgun on the mapping and analysis phases.

And if Yogi is right, the Human Genome Project will continue to step up and make the clutch hit.

Berkeley Lab View

Published every two weeks by the Communications Department for the employees and retirees of Berkeley Lab.

Reid Edwards, Public Affairs Department head

Ron Kolb, Communications Department head

EDITOR

Monica Friedlander, 495-2248,

[email protected]

Associate EDITOR

Lyn Hunter, 486-4698 [email protected]

STAFF WRITERS

Dan Krotz, 486-4019

Paul Preuss, 486-6249

Lynn Yarris, 486-5375

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Jon Bashor, 486-5849

Allan Chen, 486-4210 David Gilbert, 925-296-5643

FLEA MARKET

486-5771, [email protected]

Design & Illustration

Caitlin Youngquist, 486-4020

TEID Creative Services

Communications Department

MS 65, One Cyclotron Road, Berkeley CA 94720

(510) 486-5771

Fax: (510) 486-6641

Berkeley Lab is managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy.

Online Version

The full text and photographs of each edition of The View, as well as the Currents archive going back to 1994, are published online on the Berkeley Lab website under “Publications” in the A-Z Index. The site allows users to do searches of past articles.

People, AWARDS & HONORS

Cavalleri Wins EURYI Award

Materials

scientist Andrea Cavalleri in his laboratory

Materials

scientist Andrea Cavalleri in his laboratory

What would you say if you’d just been awarded a $1.6 million grant? Andrea Cavalleri, a physicist in the Materials Sciences Division, had this reaction: “It’s brilliant! I love it when people call me up to offer me one and a half million dollars!” Cavalleri has just returned from Sweden where he received a European Young Investigator Award from the European Science Foundation. This is the first year the EURYI Awards have been presented and Cavalleri is one of 25 inaugural recipients. The EURYI Awards are aimed at encouraging outstanding young researchers all over the world to work in Europe and lead their own research team.

Cavalleri won the award primarily for his femtosecond x-ray studies of complex materials, which include both bulk solids and nanosized particles of transition metal oxides. He came to Berkeley Lab about three years ago, joining the research group of Robert Schoenlein and Charles Shank. He has been conducting time-resolved x-ray spectroscopy studies at the ALS and recently made the first time-resolved x-ray absorption measurements on a femtosecond time scale. He has also been doing research with visible light at pulse lengths of 10 femtoseconds.

Prior to his coming to Berkeley Lab, Cavalleri worked at UC San Diego, where he conducted pioneering studies of phase transitions in solids using time-resolved x-ray diffraction techniques. This, too, was done on a femtosecond timescale.

“Femtosecond x-rays are one of the scientific frontiers, in terms of both research and instrumentation,” Cavalleri says. “I have been very involved with the current femto-second beamline at the ALS (Beam-line 5.3.1) and with the new femtosecond beamlines that will soon be built (Beamlines 6.0.1 and 6.0.2).”

A native of Italy, Cavalleri received his bachelor’s, master’s and Ph.D. degrees from Italy’s Universitá di Pavia, although he did his dissertation research at the Institute for Laser and Plasma Physics at the University of Essen in Germany. He was nominated for the EURYI Award by Oxford University.

Cavalleri has not yet decided his next step, but Schoenlein, his group leader at MSD, would like to see him remain with Berkeley Lab in some capacity.

“The EURYI Award is a significant honor for Andrea and also a significant opportunity, as it comes with funding to start his own research program in Europe,” Schoenlein said.

“Of course we would like to see him stay here, particularly with the new femtosecond beamlines being built at the ALS, but I’m sure he will be successful in whatever he chooses to do.”

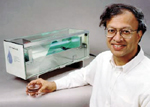

Tech Museum Award to Ashok Gadgil

By ALLEN CHEN

Ashok

Gadgil with UV Waterworks.

Ashok

Gadgil with UV Waterworks.

Ashok Gadgil of Berkeley Lab’s Environmental Energy Technologies Division was selected by the Tech Museum of Innovation to receive a 2004 Tech Museum Award in the health category. Located in San Jose, the Tech Museum is honoring 25 individuals “who leverage new and existing technologies to benefit humanity.”

A panel of international judges assembled by the Center for Science, Technology & Society at Santa Clara University reviewed applications from around the world and chose Gadgil’s work from a field of 320 candidates from 80 countries. The award recognizes Gadgil’s work in developing UV Waterworks, a device that disinfects drinking water inexpensively. About 1.2 billion people in the world do not have access to safe drinking water, and the World Health Organization estimates that on average 40 children die every hour because of diseases contracted through contaminated water.

UV Waterworks provides 15 disinfected liters of water per minute — enough water for a village of 2,000 at a cost of about $1.50 per person per year — by using ultraviolet light to kill disease-causing germs. Through a startup company, Waterhealth International, UV Waterworks devices are providing safe drinking water in Mexico, the Philippines, and other developing nations around the globe.

The Tech Awards were inspired in part by the State of the Future report of the Millennium Project of the American Council for the United Nations University, which recommends ways of accelerating scientific breakthroughs to improve the human condition.

Gadgil will receive his award during a black-tie awards gala on Nov. 10, where Silicon Valley leaders and delegates from the United Nations will honor the 25 laureates.

Ritchie Wins Nadai Award

Robert O. Ritchie, MSE Professor and senior faculty scientist in the Materials Sciences Division at Berkeley Lab, is the recipient of the Nadai Award for 2004 given by the American Society for Mechanical Engineering. The award was established in 1975 to recognize distinctive contributions to the field of engineering materials. Ritchie was cited “for seminal experimental and theoretical contributions to the field of fracture and fatigue of a broad class of structural materials.” He will be presented with the award at the 2004 International Mechanical Engineering Congress of ASME in Anaheim, Calif., in November.

Correction

Flea Market

- AUTOS & SUPPLIES

- ‘00 DODGE GRAND CARAVAN SE, 4 dr, auto, ac, ABS, repair insur, exc cond, 82K mi, $8,300/bo, Uri, 643-4078, 295-3029

- ‘95 GEO PRIZM, 4-dr sedan, teal green w/ beige inter, clean in/out, auto, radio/cass, 55K mi, reg pd through 9/05, $3,100, Janice, X4943, (925) 631-1131 eve

- ‘93 HONDA CIVIC LX, 5 sp, 154K mi, ac, ABS, cruise, pwr win/doors, alarm, $1,900, Carole, X2603, (415) 435-6639

- ‘91 FORD ESCORT GT hatchback, 2 dr, auto, 220K mi, red, am/fm, sunrf, good cond, maint rec’s, $1,500, Kei, X2373

- ‘84 BMW 633csi, auto, good cond, CD player, am/fm, sunrf, new rims & tires, black leather inter, 180K mi, $4,500, Regina, X4311

- HOUSING

- ALAMEDA, spacious 2 bdrm apt in Victorian bldg, nr shop/rest/pub trans, 1st flr unit, lots of light, no pets/smok, $1,250/mo, Janice, 8953584

- ALBANY 2/2 condo, on Park hill, fully furn, 1,234 sq ft, sunny, quiet & eleg, laundry rm, views, pool, DSL, exer & rec rms, 2-car garage, 848-1830, [email protected]

- ALBANY, 2 bdrm/2 bth condo, partial furn, clean, spectacular view, pool, tennis ct, 24-hr sec, garage, laundry rm, exer & rec rms, bus/BART to LBNL/UCB, nr shopping, no pets/smok, 1-yr lease, avail 9/10, $1,550/mo+dep, Rose, X5124, 708-2228, 234-0687, [email protected]

- BERKELEY, studio in-law apt, sep ent, quiet, nr shops/rest/BART/UC, incl w/d, water, garbage, 12-mo lease, no pets/smok, $525/mo + util, Vlad or Linda 849-1579, [email protected]

- BERKELEY, newly remodeled, lge studio + apt, downstairs in home, avail 9/25, 10 min walk to LBNL, pub trans, priv ent, bay view, garden, kitchen, bath, all utils, cable TV, internet, $1,000/mo+occas pet/garden sitting. John, [email protected], 841-7875

- BERKELEY, 2 bdrm/1 bth, din room, offstr park, w/d, dw, refrig, partially furn w/ beds, tables, chairs, sofa, dishes, etc, lease from Sept- May, June & July possible, gardener incl, $1,700/mo, no pets, [email protected], Cheryl, (401) 273-5928

- BERKELEY HILLS, sm 1 bdrm/1 bth downstairs apt in family home, kitchenette, liv rm w/ fp, bay view, some furn, sep priv ent, rustic, quiet, safe, nr Lab, $800/mo+$100/mo util+last mo+dep, Penney, 849-3043

- NORTH BERKELEY, 1 bdrm/1 bth, fully furn upper flat, incl dishes, linens, put phone line, laundry, deck, fp, offstr park, avail Sept 21, Oct 1, no smok/pets $1,000/mo, Rochelle, (415) 435-7539

- NORTH BERKELEY by wk/mo, fully furn 1/1 flat, quiet, spacious, dish TV, laundry rm, priv garden, gated carport, walk to Lab shuttle/UCB, 848-1830, [email protected]

- NORTH BERKELEY, lge 1 bdrm, studio in 6-unit apt, sunny, freshly painted upper level, in gourmet ghetto, walk dist to UBC, LBL shuttle, downtown, partly furn, kitchen, full bth & 2 closets, free laundry, offstr park, water/garbage incl, no/smok/ pets, avail now, $995/mo+ $1,990 sec dep, 1-yr lease, [email protected], Andris, cell (925) 989 4518, (925) 989 4201

- NORTH BERKELEY HILLS, lge rms to share, 2 priv bdrms in 4 bdrm/2 bth house, quiet resid area, hardwd flr, nr Tilden Park, close UC/LBNL, lge liv w/ fp, balcony & beamed ceiling, lightly furn TV/VCR, piano, w/d, upper level bdrm, $700/mo, lower-level bdrm, $690/mo, $1,000 sec dep, 1 pers/bdrm, ethernet cables, shared util, no smok/drugs/pets, 1-yr lease pref, avail now, cell, (925) 989- 4518, (925) 989-4201, [email protected]

- MISC ITEMS FOR SALE

- CHAIR electric lift/recliner, Pride model TMR-58, green, w/heavy duty lift actuator exc cond, $380, Ron, X4410, 276-8079

- COFFEE TABLE, solid oak, lifts up for serving dinner, $100; solid oak ent ctr for lge TV & audio, $150; full size blue denim couch, $200, all in exc cond, Steve, (209) 836-0913 am or X7607 after 3 pm

- ENTERTAINMENT CENTER, hutch & base, 2 pocket doors, VCR/DVD box, elec outlet, holds most 36’’ TVs, 2 adj shelves, 2 drawers, $350; dining rm table w/ 6 matching ladder back chairs, $300; square cocktail table, $50, Sallie, X6955, 790-3446

- QUARTER HORSE, Capt Nemo, very versatile, gelding, chestnut, age 11, 15.3H. friendly disposition, loves to jump, exp hunter-jumper, won blue ribbons at B-level shows & comp at novice level, no health problems, $10,000, Steve, X6730, 769-7400

- SKIS, Dynastar Outland T-160, size 5’3”, 2-yrs old $40; Salomon XSCREM 700, size 5’, 2-yrs old, $25, both in good cond, buy both for $60, Nanyang, (650)-926-2252

- WANTED

- 35MM CAMERA, manual controls/settings for high school photo class, Ruth, 526-6730 or 526-2007

- VACATION

- NORTH LAKE TAHOE house at Kings Beach, 3 bdrm/2 bth, sleeps 6, quiet cul-de-sac, 1 mi from public beach, no smok/pets, $135/night, 2 night min+$75 cleaning fee or $675/wk, Vlad or Linda, 849-1579

- PARIS, FRANCE, nr Eiffel Tower, furn, eleg 2 bdrm/1 bth apt, avail by wk/mo, close to everything, 848-1830

Flea Market Policy

Ads are accepted only from Berkeley Lab employees, retirees, and onsite DOE personnel. Only items of your own personal property may be offered for sale.

Submissions must include name, affiliation, extension, and home phone. Ads must be submitted in writing (e-mail: [email protected], fax: X6641,) or mailed/delivered to Bldg. 65. Email address are included only in housing ads.

Ads run one issue only unless resubmitted, and are repeated only

as space permits. The submission deadline for the October 1 issue

is Thursday, September 23.

Philip H. Abelson: A Force in Science for 60 Years

Philip Hauge Abelson

Philip Hauge Abelson, a world-class scientist, colleague of Ernest Lawrence, and editor of Science magazine for 23 years, died in Washington D.C. on Aug. 1. He was 91.

One of the nation’s first nuclear physicists, Abelson was co-discoverer of neptunium, worked on the Manhattan Project, and was among the first to analyze the bacterium E. coli. He was trained in physics and chemistry, but his expertise and impact on science also reached deep into the fields of biology, geology, biochemistry, and engineering.

“For us relative newcomers as well as those whom he brought here, his loss marks the end of an era,” wrote Science editor Donald Kennedy in the current issue of the magazine. “As an extraordinary role model here at Science, he cared about the full breadth of scientific work, having himself made major contributions in fields from nuclear physics to geology.”

Born in Tacoma, Wash., Abelson obtained his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Washington State University. After graduating, he began his doctoral program in physics with Lab founder Ernest O. Lawrence and received his Ph.D. from UC in 1939. Here he also collaborated with two other Nobel winners: Luis Alvarez and Edwin McMillan. With McMillan he worked on the discovery of neptunium by bombarding uranium with neutrons.

In 1944 Abelson became the head of the Naval Research Laboratory in Philadelphia, where he conducted research that in effect led to the development of the first nuclear-powered submarine. Later he shifted his interest to biology and geology. In 1955 he published a book that emphasized the importance of E. coli in genetic engineering.

In 1987, Abelson received the National Medal of Science, one of many honors and awards bestowed on him over the years. He also published nine books on subjects that touched on almost all fields of science. It is noteworthy that Abelson conducted much of his research and writing while simultaneously serving as editor of Science magazine from 1962 to 1985.

George Brecher: Hematology Pioneer

George Brecher, a pioneer of modern blood analysis and a researcher in Berkeley Lab’s Life Sciences Division until the end of his life, died on July 5 from complications from Parkinson’s disease. He was 90 years old.

Brecher obtained his medical degree in his native Czechoslovakia before emigrating to England for additional medical training in 1939. He came to the United States in 1942 and served as a captain in the U.S. Army’s medical corps from 1944 to 1946.

After his military service he joined the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., where he headed the hematology section of the Department of Clinical Pathology. That’s where he made important contributions to the laboratory practice of hematology, including the automated analysis of blood cells. Recognizing the impact of laboratory science on health care delivery, he introduced computers to the clinical laboratory to collect, summarize and share data.

In 1966, Brecher founded the department of laboratory medicine at UCSF. He remained a member of the faculty there even after retiring from the chairmanship of his laboratory, and continued to carry out research at Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley.

His many honors included the Distinguished Service Medal of the U.S. Public Health Service, the French Legion of Honor, and the Medal of Merit of the Charles University in Prague, his alma mater. He was also a past president of the American Society of Hematology and a member of the Association of American Physicians.

He is survived by his wife, Eva Brecher of Berkeley, daughter Eva Baker, stepchildren Manuel Buchwald, Miguel Buchwald, Monica Sullivan, and Claudio Buchwald, and three grandchildren.

— Monica Friedlander