Hotter

Summers Predicted by 2100

Safety Is Top Priority

for Director Chu

Hotter Summers Predicted by 2100

One hundred years from now, summers in Los Angeles may be as scorching as summers in the Mojave Desert. But it doesn’t have to be that way, according to a team of 19 scientists that includes Berkeley Lab’s Norman Miller and Larry Dale.

If energy use continues as usual, by 2100 the Sierra snowpack could

decline between 70 and 90 percent.

In a study published in the Aug. 16 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the research team predicted that Californians could experience substantially hotter summers by the end of the century, which may lead to an increase in heat-related deaths and water and energy shortages. Just how hot depends on what’s done between now and then.

The researchers analyzed two greenhouse gas emission scenarios recently presented by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a United Nations-formed organization that informs the world’s policymakers on climate change and impacts. One scenario assumes an energy-use trajectory similar to the present course, meaning rapid introduction of new technologies, extensive economic globalization, and a fossil-intensive energy path. Under this scenario, by 2100 there may be six times the 1990 levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, causing summer temperatures in Calif-ornia to soar as high as 18 degrees Fahrenheit above current temperatures.

The other scenario takes into account the adoption of green alternatives such as fuel-efficient technologies, a stronger role of local governments in fostering environmentally friendly policy, and a rapid transition to service and information economies. Under this scenario, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels peak at double the 1990 levels by mid-century, then slowly decline to below current-day levels. Summer temperatures in California only rise between 4 and 5 degrees Fahrenheit by 2100.

“These aren’t the absolute worst and best case scenarios,” says Miller, a scientist in the Earth Sciences Division. “But one of the purposes of this study is to let people know there is a choice. Our energy policy in the U.S. has consequences, and we have an influence on those consequences.

As co-authors of the paper, Miller and Dale, who works in the Environmental Energy Technol-ogies Division, conducted analyses related to heat waves, temperature extremes, water resources, and snowmelt, using projections from two state-of-the-art climate models with low and medium sensitivity.

If no measures are taken, summers in Los Angeles could be as hot as

those in the Mojave desert by next century, according to a recent

study.

The study comes as a confusing mix of global warming-related fact and fiction bombards the public. It’s the cover story of this month’s edition of National Geographic Magazine, in which strong evidence of global climate change is presented. And people flocked to multiplexes this summer to see an unrealistic action movie, The Day After Tomorrow, in which abrupt climate change triggers tsunamis and ice ages. Although the Statue of Liberty won’t be engulfed by a giant wave if high fossil fuel emissions continue unchecked, the projections presented in the study don’t necessarily soften the blow.

According to the study, in the fossil- fuel intensive scenario, Los Angeles may experience up to six times more heat waves each summer toward the end of this century, with heat-related- mortality increasing five to seven times. In addition, by 2100 the Sierra snowpack could decline between 70 percent and 90 percent from current levels, which would fundamentally disrupt California’s water rights system.

But the study also projects that if energy efficient technologies are given a chance, and local governments take a lead role in implementing responsible energy policy, Los Angeles heat waves will only quadruple in frequency, heat related mortality rates will only double or triple, and between 30 percent and 70 percent of the Sierra snowpack will vanish.

“This is a good opportunity for California government to demonstrate its leadership role in environmental policy,” says Miller. “If the state can commit to change, the nation will follow.”

In addition to Berkeley Lab, re-searchers from several universities and research institutions contribut-ed to the study, including Stanford University, UC Berkeley, the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and the National Center for Atmos-pheric Research. Katharine Hayhoe of South Bend, Indiana-based ATMOS Research and Consulting is the lead author.

Safety Is Top Priority for Director Chu

Berkeley Lab Director Steve Chu says that at Stanford University, where he worked the last 17 years, a culture was established where safety was taken very seriously.

The construction site for the Molecular Foundry displays a vivid reminder

to put safety first.

“The regulations were there to protect us,” he said. “If a member in a research group did something that was unsafe or potentially hazardous, that person would be held accountable by the other members of the group. Basically, a relaxed attitude toward safety and safety regulations was considered to be antisocial behavior, since it puts everybody in the lab at risk.”

That’s one reason he puts safety at the top of his priority list in his first months on the job. Another reason is that safety is taken very seriously by the director of the Department of Energy’s Office of Science, Ray Orbach. “He compares our accident and injury performance to the best practices in industry,” said Chu. “His goal is to have us in the top 25 percent group of peer comparisons, and eventually in the upper 10 percent.”

The Laboratory’s newly hired division director for Environment, Health and Safety, Phyllis Pei, recently joined Chu in urging the Laboratory’s top managers to continue to emphasize safety in the lab, in the office, on the roadways and in construction zones. The goal is to prevent hazards, repeat injuries and unsafe behavior.

Pei outlined an ambitious campaign designed to develop ways to improve the Lab’s safety program and to raise the awareness of all employees about safety. Some of the activities already underway include:

- Stanford vice provost of EH&S, Larry Gibbs, volunteered to spend an afternoon at Berkeley Lab this week reviewing our safety program. EH&S directors from industrial research labs with exemplary performance will also be consulted.

- Representatives from all divisions engaged in a roundtable discussion with Gibbs, Chu and Pei on Wednesday about safety experiences and issues.

- Employee focus groups, safety walkthroughs, and outside speakers will also be used to gather input on how the Lab can improve its safety culture.

“We do great science here,” Chu told his division directors. “If this laboratory fails, it will be because of a financial problem or because of a safety issue. If we don’t pay attention to these issues, we won’t be able to do the science.”

Chu said the key is to “get it into the culture,” especially for the younger employees like postdocs and graduate students. “One of our biggest challenges,” he said, “is to convince 25-year-olds that they aren’t immortal.”

The recent trend is good. Berkeley Lab received kudos from the Office of Science for its performance so far in fiscal year 2004, in which accident and injury rates are almost half of what they were in the prior two years. But some incidents over the past two months have indicated some slippage in those rates.

“This is something we need to do over time,” Chu said. “We will design a program that is self-sustaining and ongoing. I’d like to get the entire Lab to adopt a safety mindset, with individual ownership and accountability, led by active and visible involvement by management. Safety is a big issue for me.”

Competition Hot at Chili Cook-off

Lab

Director Steve Chu (top, left) samples the “hydrozoic acid”

chili of the Hot Stuff team. But it was the culinary genius of Chilly

Willy (above) that won the judge’s vote.

Lab

Director Steve Chu (top, left) samples the “hydrozoic acid”

chili of the Hot Stuff team. But it was the culinary genius of Chilly

Willy (above) that won the judge’s vote.

Facilities Division personnel turned out in force at lunchtime on Aug. 24 for the division’s first Chili Cookoff. The competition drew 14 contestants, who served up their fiery fare from creatively decorated booths in the Building 69 parking lot.

Judging was provided by the Alameda County Fire Department, which dispatched Berkeley Lab firefighters Tom Neuerberg, Maureen Noon, Dave Piepho and Jason Lemoine to the scene. The firefighters awarded the prize for best chili to the Chili Willy team of Harry Bash, Phil Bach, and Victor Hepa. Team 5 came in second with an “isotopic” chili, followed in third place by the Hot Stuff team’s “hydrozoic acid” chili. Hot Stuff grabbed the prize for best booth display with its hazardous materials theme, followed by Snappin’ Chili Sensations in second and Chow’s Chili Bowl in third.

Facilities Division head George Reyes conceived the cookoff as a

team-building event, and although his “Four-Alarm Chili”

entry was not a winner, the cookoff definitely was. Additional credit

for making the event a success goes to the organizing committee, which

was headed by Melanie Woods and included Desiree Elvira, Sarah Morgan,

Teji Dhaliwal, Janice Sexson, and Tammy Thompson.

UC Athletes Shine in Athens

If UC Were a Country …

… its 2004 medal total would have been exceeded by only six other nations (U.S., Russia, China, Australia, Germany, and Japan). UC sent 100 athletes to Athens — more than many countries — and they brought home no less than 36 medals, 13 of them gold.

Natalie Coughlin

Winning multiple medals were swimmers and UC alums Natalie Coughlin of UC Berkeley, with five medals (two gold, two silver, and a bronze), and Jason Lezak of UC Santa Barbara, with two golds and a bronze.

Coughlin, a recent Cal grad who turned 22 during the Olympics, won more medals than any female swimmer in Athens. Hers was also the best Olympic performance by a Bay Area athlete since Cal’s Matt Biondi won seven swimming medals at the 1988 Seoul Games.

The gold-medal U.S. softball team included five UCLA-trained athletes: Lisa Fernandez, who at 33 won her third consecutive Olympic gold medal, Tairia Flowers, Aman-da Freed, Stacey Nuveman, and Natasha Watley.

Joy Fawcett of UC Berkeley and UCLA helped the US soccer team to Olympic victory. Other gold medal winners with UC connections included Pete Cipollone of UC Berkeley in men’s eight rowing, Joanna Hayes of UCLA in the 100-meter hurdles, and Monique Henderson of UCLA in the women’s 1600-meter relay.

UC’s performance continued a long and proud history of participation in the Olympic Games. The University sent athletes from Berkeley, Irvine, San Diego, Santa Barbara, and UCLA — whose athletes have won a gold medal in every Olympics since 1932 (with the exception of the 1980 boycott).

UC Berkeley sent an especially diverse international contingent. In addition to athletes representing the United States, Cal Olympians include a basketball player for New Zealand, crew members for Norway, Canada, and Serbia-Montenegro, a softball player for Greece, and swimmers representing Croatia, Poland, Lithuania, Serbia-Montene-gro, Slovenia, Malaysia, Brazil, Aus-tralia, the Philippines, and Sweden.

UC experts a strong presence behind the scenes

UC’s contribution to the success of the 2004 Olympics extended beyond its talented athletes. Experts from various campuses helped out in areas ranging from nutrition and fitness to biomechanics and injury prevention. Among them was champion speed skater Eric Heiden, now a UC Davis assistant professor of sports medicine who works with the U.S. Olympic Committee as a team physician. Heiden was the first person to win five individual gold medals when he swept the men’s events in the 1980 Winter Olympic Games.

UC Berkeley researchers lead reconstruction of ancient temple

It’s been 2,300 years since the Temple of Zeus stood watch over the Panhellenic Games at Nemea, one of the ancient contests that gave rise to the modern Olympic Games. When athletes from around the world gathered in Athens last month, the temple was still there, but time has taken its toll. Built in 330 B.C., the structure was once surrounded by 32 columns, of which only three survived. In 2002, UC Berkeley researchers led the reconstruction of two more columns. Stephen Miller, a UC Berkeley professor of classics, headed the project and will be succeeded by Nicos Makris, a UCB professor of structural engineering.

The project is part of a larger, ongoing effort that Miller began more than 30 years ago in Ancient Nemea, a tiny town 80 miles from Athens, where he has unearthed the athletic stadium, entrance tunnel, track, bathhouse, and what is likely the world’s oldest athletic locker room.

Work is now underway to reconstruct four more columns in the hope of preserving the ancient structure from further damage. Even in ruins, the temple has withstood the test of time, the savagery of war, and the frequent earthquakes that have rocked the area over the past 23 centuries.

“The ancient Greeks and we share a fundamental creativity that marks the human spirit at its best,” Miller said. “We share an impulse toward a higher civilization that leaves a record of human accomplishment, and that serves as a beacon to future generations.”

Berkeley Lab View

Published every two weeks by the Communications Department for the employees and retirees of Berkeley Lab.

Reid Edwards, Public Affairs Department head

Ron Kolb, Communications Department head

EDITOR

Monica Friedlander, 495-2248,

[email protected]

Associate EDITOR

Lyn Hunter, 486-4698 [email protected]

STAFF WRITERS

Dan Krotz, 486-4019

Paul Preuss, 486-6249

Lynn Yarris, 486-5375

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Jon Bashor, 486-5849

Allan Chen, 486-4210 David Gilbert, 925-296-5643

FLEA MARKET

486-5771, [email protected]

Design & Illustration

Caitlin Youngquist, 486-4020

TEID Creative Services

Communications Department

MS 65, One Cyclotron Road, Berkeley CA 94720

(510) 486-5771

Fax: (510) 486-6641

Berkeley Lab is managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy.

Online Version

The full text and photographs of each edition of The View, as well as the Currents archive going back to 1994, are published online on the Berkeley Lab website under “Publications” in the A-Z Index. The site allows users to do searches of past articles.

ALS Sheds More Light on High Tc Superconducting Mystery

The mystery behind high-temperature superconductors is one step closer to being solved thanks to recent experimental results at the Advanced Light Source (ALS). A team of researchers led by physicist Alessandra Lanzara, who holds a joint appointment with Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division (MSD) and UC Berkeley’s Physics Department, has produced the first direct evidence of “a significant and unconventional” role in high temperature superconductivity for phonons, vibrations in the ions that form the lattice of a superconductor’s crystal.

Standing

at ALS Beamline 10.0.1, where they found new evidence for the importance

of phonons to high-temperature superconductivity, are (from left)

Alessandra Lanzara, Shuyun Zhou, Chris Jozwiak, Jef Graf and Gey-Hong

Gweon.

Standing

at ALS Beamline 10.0.1, where they found new evidence for the importance

of phonons to high-temperature superconductivity, are (from left)

Alessandra Lanzara, Shuyun Zhou, Chris Jozwiak, Jef Graf and Gey-Hong

Gweon.

“We have found the first direct evidence of electrons interacting with phonons in the high temperature superconductors, and discovered a strong correlation between the strength of the electron-phonon interactions and superconductivity,” Lanzara says. “The ALS is the only place in the world were we could have done this experiment with such high precision.”

Superconductivity is a state in which a material loses all electrical resistance: once established, an electrical current will flow forever. Following the discovery in the 1950s of niobium-based metal alloys that become superconducting at critical temperatures around 18 degrees Kelvin (18 K), superconductivity has become a staple of high-tech magnet technology in scientific research. However, the cost and difficulty of chilling these metals with liquid helium limit their applications elsewhere.

The discovery in the 1980s of doped copper oxides, or cuprates, that become superconducting at critical temperatures above the 77 K boiling point of liquid nitrogen (meaning they are much cheaper to chill than metal superconductors) brought forth the tantalizing prospect of room temperature superconductors — and their promise of such prizes as dirt-cheap electrical power and magnetically levitated high-speed trains. For this promise ever to be realized, however, scientists need a better understanding of the physics behind high-temperature superconductivity.

The physics behind low-temperature superconductivity has been successfully explained by BCS theory, named for its Nobel-prize winning authors, John Bardeen, Leon Cooper, and Robert Schrieffer. BCS theory says that a superconductor loses electrical resistance through the formation of electron pairs, dubbed Cooper pairs, in which any motion on the part of one member of the pair instantly causes an equal countermotion in the other. Cooper pairing cancels out any disruption in the flow of an electrical current caused by crystal impurities, a source of electrical resistance.

Electrons that would naturally repel one another because of their mutual negative charge are able to pair up because of the interaction, or “coupling,” of one of them with a phonon, which can be thought of as a sort of atomic sound wave. The first electron alters the phonon, and the second electron is affected by this alteration, like passing ships influencing each other’s motion through their effect on the surrounding waves.

The prevailing scientific thought has been that electron-phonon coupling plays little or no role in high temperature superconductivity. Lanzara and her colleagues thought otherwise. In a paper first published in the July 8, 2004 issue of Nature, they described a unique experiment on the ALS undulator beamline, 10.0.1, using a technique called ARPES, for angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy.

Co-authoring the Nature paper with Lanzara were MSD scientists Gey-Hong Gweon and Jeff Graf, UC Berkeley’s Dung-Hai Lee and Shuyun Zhou, and Hide Takagi and Takao Sasagawa with Tokyo University in Japan.

“We’ve been able to spell out for the first time the way the two key elements in high temperature superconductivity, magnetism and phonons, interact in an important way,” says Lanzara.

With ARPES, light is flashed on a sample, causing electrons to be emitted through the photoelectric effect. Measuring the kinetic energy of emitted electrons and the angles at which they are ejected identifies their velocity and scattering rates, which, in turn, yields valuable information about electron interactions within the sample. Lanzara and her colleagues used ARPES to study Bi-2212, a cuprate doped with bismuth, strontium and calcium that becomes superconducting at 92 K.

As with all cuprate superconductors, the crystal structure of Bi-2212 is like a layer cake. In this case, two-dimensional layers of oxygen and copper atoms, interspersed with strontium and calcium atoms, alternate with two-dimensional layers of oxygen and bismuth. For their experiments, Lanzara and her colleagues replaced some of the normal oxygen-16 in the layer cake with a heavier isotope, oxygen-18, then compared ARPES measurements.

By lighting their samples with the laserlike beams of photons generated at ALS beamline 10.0.1, Lanzara and her colleagues obtained a high enough degree of angular and energy resolution that they could determine the differences in electron dynamics resulting from a crystal lattice made heavier and stiffer by the oxygen-18 substitution.

“The high degree of angular and energy resolution was critical,” says Lanzara. “We were comparing two samples of two different isotopes, and in order to claim any change induced by the isotope substitution, it was very important that the data be unambiguous. The capabilities of ALS beamline 10.0.1 are unique in this respect.”

From their data, Lanzara and her colleagues concluded that in high-temperature superconductors, phonons stabilize the Cooper pairing of electrons triggered by antiferromagnetism. The antiferromagnetism arises when the magnetic spins of electrons in the lattice align themselves with neighboring spins pointing in opposite directions. This alternating electron spin arrangement, called a “singlet,” is very similar to the spin-Peierls systems found in one- dimensional chains. In that system, the formation of spin-singlet electron pairs enhances the electron-phonon interaction and vice versa. Lanzara and her colleagues believe the same thing happens in high temperature superconductors.

“The formation of the Cooper pair is mediated through the phonons, and at the same time there is a feedback from the anti-ferromagnetic interaction, so the two enhance one another,” says Lanzara. “This is a qualitatively new proposal for explaining high temperature superconductivity, and goes beyond any previous proposal based on the antiferromagnetic interaction alone.”

The Telomere Crisis: A Narrow Gate to Breast Cancer

What event signals the onset of breast cancer? New research by a team from Berkeley Lab’s Life Sciences Division and UC San Francisco points to a late phase in the life of cells — the “telomere crisis.”

Structures called telomeres protect the ends of chromosomes, insuring that the cell’s genome is copied accurately during cell division. But telomeres grow shorter with each new generation, until chromosomes may be miscopied or even break, triggering the body’s defense mechanisms to kill unstable cells.

By evading these defenses a cell can keep replicating and cause cancer. It’s a sign of trouble if the cell starts producing telomerase, a protein-RNA complex that maintains telomeres. Some researchers think that telomerase production results from a fault in the stem cells that give rise to breast cells. The Berkeley Lab–UCSF team, led by Joe Gray, director of the Lab’s Life Sciences Division, showed that a cell’s genomic instability itself can turn on telomerase.

The team looked at “usual ductal hyperplasia,” milk-collecting ducts in which cells have proliferated excessively. When these pass through the telomere crisis, Gray says, “the cells in which telomerase is activated can then proliferate indefinitely to form the next stage of cancer, known as ‘ductal carcinoma in situ.’” The cancer may progress further, invade other parts of the breast, and escape to other organs.

In human studies this order of events is just association, Gray says, “because we can’t look at the same tissue all the way through the crisis.” So the researchers studied what happened when they induced a culture of human mammary epithelial cells, HMEC, derived from normal breast tissue, to undergo telomere crisis.

“With HMEC in vitro we can follow the progression all the way through crisis, compare this to what we observe in actual tissue specimens from patients, and see if they are similar,” says Gray. What they observed matched the situation in human tissues: a dramatic increase in genome instability after telomere crisis, just as in samples of ductal carcinoma.

This suggests that people at higher risk of developing cancer can be identified in advance by measuring telomerase activity, genome instability, and other signals in the clinic. And it indicates promising lines of research for treatment, some already being tested.

“In situ analyses of genome instability in breast cancer,” by Koei Chin, Carlos Ortiz de Solor-zano, David Knowles, Arthur Jones, William Chou, Enrique Garcia Rodriguez, Wen-Lin Kuo, Britt-Marie Ljung, Karen Chew, Kenneth Myambo, Monica Miranda, Sheryl Krig, James Garbe, Martha Stampfer, Paul Yaswen, Joe W. Gray, and Stephen J. Lockett, appears online in Nature Genetics.

New Critters Queue up for JGI’s Community Sequencing Pipeline

Emerging from the soil and water of toxic waste sites and from the depths of the oceans, micro- and macroscopic creatures are now lining up to have their genetic fortunes told through the Joint Genome Institute’s Community Sequencing Program (CSP). Joining them will be an antibiotic-resistant strain of the food-borne pathogen Staphylococcus, along with a rich diversity of other terrestrial and aquatic organisms. These and other organisms are poised to close important gaps in our understanding of the tree of life and keep JGI’s sequencers humming 24/7 over the next year.

The soon-to-be-sequenced moss Physcomitrella patens

“There’s the perception that the genetic diversity among animals — ranging from humans to worms — is enormous,” says JGI Director Eddy Rubin. “But the reality is it pales in comparison to the diversity between the microbes that make up the bulk of the biomass on the planet. With these new selections JGI will help to advance knowledge across such vital topics as alternative energy production and bioremediation, and to address important questions of evolution and development.”

The CSP will allocate roughly 15 gigabases (billions of letters of genetic code) of sequencing — about 50 percent of JGI’s annual capacity — for the 23 projects selected from nearly 60 submitted earlier this year.

Adding to JGI’s leadership in plant genomics will be the characterization of the moss Physcomitrella patens which, along with the Gemmiferous Spike Moss Sela-ginella moellendorffii, will be the first nonflowering vascular plants to be sequenced. Predating flowering plants by some 200 million years, mosses were among the first plants to colonize the land 450 million years ago.

“Human comparative genomics has benefited from having a series of genome projects — mouse, puffer fish, fruit fly, worm,” says Brent D. Mishler, director of the University and Jepson Herbaria and a professor of integrative biology at UC Berkeley. “Physcomitrella will be a triumph for international plant science.”

Evolutionary genomics researchers have their sights set on the first representatives to be sequenced from the large animal group Lophotrochozoa. These include the leech Helobdella, long used as a model system by biologists studying embryological development and functions of the nervous system, the polychaete worm Capitella, and the mollusk Lottia.

Other CSP projects in the pipeline include:

- A targeted evolutionary study proposed by researcher Michael Eisen

of Berkeley Lab’s Genomic Division for the construction of

functional models of regulatory sequences from a set of developmental

genes representing three diverse families of flies (Dipterans):

Coelopids, Calliphorids, and Asilids.

- Groundwater samples from the Oak Ridge National Laboratory Y12

Security Complex — site of one of the highest concentration

plumes of mobile uranium with volatile organics, aluminum, nickel,

nitrate technetium, thorium, and zinc.

- Karenia brevis, a single-celled alga responsible for the natural saltwater phenomenon known as “red tide,” which can pose a human health risk and detrimen-tally affect regional marine economies.

The full roster of CSP organisms can be found at http://www.jgi.doe. gov/sequencing/cspseqplans.html.

Down to Earth with Bo Bodvarsson

Stacked on Earth Sciences Division Director Bo Bodvarsson’s desk are papers that delve into some of the most pressing practical problems of the twenty-first century. His division is investigating ways to increase the recovery of hydrocarbons, sequester carbon dioxide underground, increase production of geothermal energy, predict climate change, clean up contaminated sites, and facilitate the safe disposal of nuclear waste. In short, he oversees a team of over 200 scientists and support staff dedicated to ensuring that future generations don’t run out of energy or inherit today’s environmental problems. The View talked with Bodvarsson about what’s needed to overcome these challenges.

VIEW: How is Berkeley Lab uniquely able to contribute to these challenging problems?

BODVARSSON: National labs offer a multidisciplinary approach to research that enables us to bring together hydrologists, geophysicists, geochemists, microbiologists, and many other disciplines and tackle very tough problems. Director Chu came to my last division town hall meeting and gave a very enlightening talk about environmental and energy issues. He strongly believes the Earth Sciences Division is a focal point of important research into many problems facing the nation and the world.

Also, today’s research cannot only be undertaken using a single-investigator, single-discipline approach. An example is a very successful partnership here at Berkeley Lab in which the Earth Sciences Division, the Physical Biosciences Division, and the Joint Genome Institute are collaborating on the Genomes to Life initiative. As earth scientists, we contribute our knowledge of the environment and contaminated sites, and help the initiative develop microbiological solutions to environmental remediation.

VIEW: What are your insights into the future of Yucca Mountain, and what scientific questions remain?

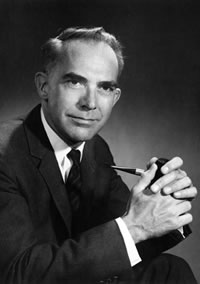

Bo Bodvarsson

BODVARSSON: The Yucca Mountain project underscores a key question common to many subsurface systems. We have real difficulties determining the locations of important flow paths of fluids in the subsurface, whether it’s water, gas, or oil. And at Yucca Mountain this is especially critical because if there is no water entering the emplacement drifts, then there is limited corrosion of waste containers and no transport of radionuclides to the accessible environment.

The July federal appeals court decision, which suggests increasing Yucca Mountain’s compliance time from 10,000 years to perhaps as much as one million years, means that we can no longer depend solely on waste containers that have a life span of tens of thousands of years. Instead, we must depend on the natural system at Yucca Mountain to isolate the waste over hundreds of thousands of years.

Based on the court decision, I have already participated in high-level DOE meetings to discuss ways to more fully understand long-term peak dose at Yucca Mountain. There are a couple of areas in which research is needed. One is neptunium solubility. The half-life of neptunium is roughly 2 million years, meaning it is a major long-term contributor to dose. The other area is the drift shadow zone, the area below drifts where we think there is very low flow of water because the drift acts like an umbrella. This dry zone could help delay radionuclide transport and minimize peak dose in the long-term.

Overall, if there is going to be geologic storage of radioactive material in the future, it probably has to be at Yucca Mountain. There is not enough time to characterize another site — and allow the nation to use nuclear power if it chooses to do so — within the next 20 years.

VIEW: What obstacles must be overcome to ensure carbon sequestration is widely used?

BODVARSSON: The key to carbon sequestration is to find a sufficient number of good subsurface reservoirs where a large volume of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases can be injected without excess leakage. As such, there are tests occurring in Texas, Germany and other locations that examine the viability of injecting carbon dioxide into subsurface formations. The technology of injecting gas underground is not the problem. The questions concern issues such as long-term geochemical effects, leakage and migration, monitoring, and using gas injection to enhance recovery of hydrocarbons. Berkeley Lab is leading the nation in characterizing these phenomena.

With a focused research effort, which I think DOE is very interested in, I think it may be possible to begin commercial applications of carbon sequestration within a decade. That is my hope. We absolutely have to begin soon if we are to mitigate the changes that we expect in the climate and the environment.

VIEW: What innovations are occurring in energy recovery?

BODVARSSON: Berkeley Lab is an active participant in DOE’s Office of Fossil Energy, especially in developing applications that use seismic and electromagnetic methods to find new hydrocarbon resources underneath the oceans and large salt bodies. Our researchers are also developing state-of-the-art models that are extremely computationally intensive. However, we are limited by our ability to secure computational power at NERSC and other supercomputers. We would like to obtain much more time on these computers, but unfortunately there is a belief that geoscience does not require intense computing. This is incorrect.

I am working to convene a workshop, to be held early next year, on the computational needs of geosciences. It was requested by Ari Patrinos, associate director of DOE’s Office of Biological and Environ-mental Research. The workshop will enable us to give DOE a rationale to carve out more computational time for earth sciences.

We also need to explore the use of methane hydrates as a possible compliment to hydrocarbon as an energy source. It is estimated that there are vast quantities of methane hydrates located in permafrost areas and underneath oceans. Berkeley Lab is one of the few science organizations supported by the DOE Office of Fossil Energy to investigate methane hydrates. We are conducting pioneering lab tests on large methane hydrate samples, and developing state-of-the-art numerical models of methane hydrate resources. We are involved in the development of strategies for the efficient extraction of gas from hydrate deposits.

VIEW: What is the future of environmental remediation?

BODVARSSON: Environmental remediation in the U.S. is up in the air right now. Natural attenuation, which means leaving contamination in place, is currently the preferred method — but it is likely that this will fail at many contaminated sites. Under this approach, we could see contamination spreading at various sites a decade from now. In the long run, it may cost much more to not remove more of the contaminants. At the very minimum, we need to conduct numerical and conceptual modeling studies of some of the key contaminated areas, and predict what will happen if we depend on natural attenuation. This will allow us to compare future observations with the predictions and allow for change in strategy wherever that is needed.

Special Car Fuels the Spirit of Environmentally-Minded Employee

When Jill Fuss sees the gas prices jump at neighborhood filling stations, a smile spreads across her face. Ditto when she reads articles on the ever-rising costs of fuel.

Jill Fuss fills her tank with restaurant vegetable oil she filters

at home.

Jill Fuss fills her tank with restaurant vegetable oil she filters

at home.

While most drivers curse these hikes, Fuss — a postdoctoral fellow in the Life Sciences Division —stays calm. She hasn’t paid for gas in over a month, even though she uses her car nearly every day.

The secret to her freedom from fossil fuel lies under the hood of her Volkswagon Jetta. The car may look like any other, but there’s a huge difference: it runs on vegetable oil.

“I was looking for a new vehicle and wanted to get one that was environmentally friendly,” says Fuss. “I also had political reasons. Vegetable oil is a domestic product and using it helps reduce dependence on foreign oil.”

After some research, she found the car of her dreams on Craig’s List: a late model Jetta converted to run on vegetable oil.

“The next step was finding my fuel source,” Fuss says. “So, I went to various restaurants in my Rockridge neighborhood to see if they’d be willing to give me their used frying oil.”

Fuss was met with puzzled looks and head scratching. Not grasping the concept, several proprietors brushed her off. But within 10 minutes, she found a willing partner at Tachibana, a Japanese restaurant on College Ave.

“We made arrangements for me to stop by every Monday evening to pick up their used oil,” she said. “This alleviates their need to pay someone for pick up and disposal.”

Fuss takes the oil to her home where, in the driveway, she has a 50-gallon drum. She pours the oil into a large 15-gallon funnel atop the drum, where it passes through a special filter. The clean oil is then hand-pumped into her car as needed.

According to Fuss, her “veggie” car performs as well as any other Jetta. And to those wondering if her car smells like shrimp tempura — it doesn’t.

“My friends have gotten down on their knees to sniff the exhaust pipe,” says Fuss, “but it seems to be odorless.”

And it’s clean, as well. This non-toxic alternative fuel reduces carcinogenic emissions by 90 percent, says Fuss, cuts particulates in half, is carbon neutral, and has zero sulfur emissions.

With the minimal amount of driving Fuss does — mainly commuting to and from the Lab from north Oakland — she figures it will take about five years to cover what she paid for the car. She anticipates saving from $40 to $50 a month on gas.

While saving money is an important factor, it wasn’t the driving force behind her decision to go veggie. As a scientist studying how cells can protect themselves against cancer, she is deeply concerned with creating a healthier environment and hopes her story will inspire others to consider alternative fuels.

“It takes a little more time and preparation, but it’s totally worth it,” says Fuss of her unique transportation mode. “I won’t put anything in my fuel tank that I wouldn’t put in myself.”

Mountain Climbing Medical Physics Pioneer Dies

One of the original members of John Lawrence’s research group at Donner Laboratory, the founder of what is today the Environmental Energy Technologies Division, and an adventurer who truly scaled new heights as a scientist, has died. William “Will” Siri passed away in his Berkeley home on Aug. 24. He was 85.

Will Siri: world class scientist, mountain climber, environmentalist

Will Siri: world class scientist, mountain climber, environmentalist

Siri, who was born in Philadelphia in 1919, joined Berkeley Lab in 1943, after earning a bachelor’s degree in physics at the University of Chicago. Like many Lab scientists at that time, he was immediately sent to work on the Manhattan Project. He returned to Berkeley after the war in 1945 and helped John Lawrence launch the field of nuclear medicine. Siri’s primary interest was the use of radionuclides to study human red blood cells.

Over the years, Siri became increasingly interested in how the blood responds to physiological stress. Combining his scientific interest with his love of outdoor adventure, he became his own best experimental subject. In 1959, he was a member of the INPHEXAN group, a joint U.S. and British scientific expedition to the South Pole to observe the effects of extreme cold on the blood and certain disease of the blood.

By 1963, Siri had established himself as perhaps the world’s foremost mountain-climbing scientist. He had conquered several formidable peaks in the Andes, including the 17,000-foot Chacoltaya Mountain, and teamed up with Sir Edmund Hillary to rescue a climber out of a deep crevasse on 27,790-foot Mount Makalu in the Himalayas. In 1963, Siri, then 43, served as the deputy leader and scientific coordinator for the first American expedition to successfully climb Mount Everest. Prior to that climb, he spent four days in a decompression chamber at Donner Lab, in an experiment to measure physiological response to high altitudes. For that experiment and for his ascent to “the roof of the world,” Siri was especially interested in the stress induced by hypoxia (lack of oxygen) and high-altitude fatigue, and the resulting effects on the production of red blood cells.

When he wasn’t climbing the world’s highest mountains, Siri hiked the Sierras with, among others, photographer Ansel Adams. He joined the Sierra Club when he first came to Berkeley and was president of that organization from 1964 to 1966, a time when its membership doubled. He served on the Sierra Club’s board of trustees until 1978 and on its National Advisory Council until his death. In 1994, he received the Sierra Club’s prestigious John Muir Award. Siri was also one of the founders, in 1961, of the Save the Bay Association, an organization dedicated to preserving the San Francisco Bay.

Siri once said he climbed mountains as “the consequence of a deranged gene,” and became involved in environmental causes because, from atop mountain peaks, he observed the world to be “small, round and polluted.”

Before retiring from Berkeley Lab in 1982, Siri founded the Energy and Environment Division. This would evolve into the Applied Sciences Division and then today’s EETD. After his retirement, Siri remained active in ecological causes until the early 1990s, when the onslaught of Alzheimer’s disease incapacitated him and contributed to his death from physical complications.

Siri is survived by his wife of 54 years, Jean Siri, East Bay Regional Parks board director and former mayor of El Cerrito, and by his daughters Lynn Siri Kimsey of Davis and Anne Siri of Philo, and two grandchildren.

At Siri’s request, there were no services.

Flea Market

- AUTOS & SUPPLIES

- ‘99 TOYOTA CAMRY LE sedan 4D, orig owner, auto, 78K mi, ac, all pwr, cruise, am/fm/cd, ABS, exc cond, $7,850/bo, Xingjiang, X7634, [email protected]

- ‘97 GRAND CARAVAN, teal, 82k mi, Mich tires, great cond, maint rec’s, orig owner, $6,650, Al, (925) 377-1096

- ‘95 VW EUROVAN CAMPER, rare & discontinued, 67K mi, 5 spd, full camper equip & pop top, keyless entry/alarm, pwr win/locks, CD, p/m, cruise, white w/ custom pinstripe, $19,500, Norm, X6724, (916) 961-8765

- HOUSING

- ALBANY, 2 bdrm duplex, avail 8/16, move-in date flex, 700 sq feet,

hardwd flrs, park in driveway, w/d in unit, nr shop/pub trans/UCB,

cats ok, no dogs, $1,325/mo, $1,325 sec dep, avail 8/15, no smok,

Nana, 548-2706, 525-1892

BERKELEY, 1 bl from UC, lge, nicely furn 1 bdrm apt, computer & DSL, $1,575/mo, Jin, 845-5959, [email protected] - BERKELEY, fully furn 1 bdrm apt nr UCB, sunny, quiet, safe, Elmwood

resid area, walk to UC/pub trans, split-level, hill view from lge

terrace, incl linen, dishes, hi-fi, VCR/DVD, microwave, pref 1 responsible,

mature, nonsmok vis scholar, 1st week of Sept until 9/05, dates

flex, $1,050/mo incl garage, Agee, agblako@ att.net, indicate phone

# and time to call

BERKELEY, lge furn 1bdrm/1bth, SF/GG views, hardwd flr/carpet, 4 closets, balcony, incl water, garbage, cable, pool, tennis, jacuzzi, sauna, gym, 24-hr sec, reserved undergr parking, storage, nr UCB/pub trans/shop/BART, $1,350/mo, $2,100 dep, 1-yr lease, $15 app fee, Jonathan, 524-4914 - BERKELEY, Grizzly Peak, 1 bdrm inlaw apt w/ sep ent, kitchen,

liv rm & bth, view, furn $950 or unfurn neg, DSL, pref tenant

for 9 mo/1 yr, Judy, (415) 713-6745

BERKELEY, 1 bdrm, lge sunny studio, freshly painted upper level in 6-unit apt in gourmet ghetto, nr UC/Lab shuttle/ downtown, partly furn, efficiency kitchen w/ range, refrig, microwave, full bthrm, free laundry, offstr park, pd water & garbage, single occup, no smok/pets, must be quiet professionals or UCB grad students, avail now, $1,025/mo+$2,000 sec dep, [email protected] - BERKELEY HILLS, fully furn rm w/ sep entry, full kitchen priv,

w/d, quiet neighborhood, lovely backyard, next to bus stop, avail

now, [email protected], Arun, 524-3851

BERKELEY HILLS, 1 bdrm/1 bth, fully furn inlaw apt, spacious liv rm/din area, cable TV, w-w carpet, marble bth, modern kitchen, patio, $1,090/mo+$50 util, nr UCB, non-smok only, Helga, 524-8308, [email protected]. - BERKELEY HILLS, by wk/mo, quiet furn, 2 bdrm/1 bth, quiet, eleg

& spacious, bay views, DSL, cable, nr UCB, Denyse, 848-1830,

[email protected]

BERKELEY HILLS, 2 bdrms in charming 4 bdrm home, share w/ 1 woman, 1 lge rm w/ lge storage closet, 1 med size rm, priv bthrm, share kitchen, liv/din rm, hardwd flrs, $950/mo, sec dep $350, Carmella, 981-6341 day, 526-7052 eve - BERKELEY HILLS, 4 bdrm/2 bth house, 3 priv bdrms in shared 2-story

house, quiet area, 1 bthrm on ea flr, lge liv rm, hardwd flrs, fp,

balcony, beamed ceiling, lightly furn, dw, w/d, gas furnace &

water heater, bdrm furn avail, ethernet to ea rm, DSL, shared util,

no smok/drugs/pets, 1-yr lease, avail now, BerkeleyRental2004@ Yahoo.com

EL CERRITO, furn 2 bdrms/1 bth in very safe neighborhd, nr elem & high schools, pub trans/BART/shop/rest, remodeled kitchen, hardwd flrs, fp, w/d, driveway for 2 cars, apple & cherry trees, gardening pd by owner, no pets, $1,500/mo+$3,000 dep, Ron or Erin, (415) 931-6295, X115 - EL CERRITO HILLS, 1 unfurn rm w/ bay view, $530, in shared furn

house w/ 4 bdrms/2 bthrms, din rm, lge gourmet kitchen, backyard,

storage space, w/d, 1 cat, pets ok, 1st +last mo + dep, avail 9/1,

Cinthia, X2889, 932-9186

EL CERRITO HILLS, spacious fully furn studio, $900, kitchenette w/ new appliances, util incl, free cable TV & laundry, 15 min to UCB, parking, walk to El Cerri-to Plaza, 7613 Errol Dr, Voya, 525-8211 - KENSINGTON, furn rm for vis scholar, own toilet, kitchen &

laundry facil, quiet, view, $550/mo, Ruth, 526-6730, 526-2007

KENSINGTON, fully furn 3 bdrm home, view, quiet setting, 1 cat, avail for vis scientist for fall term, Aug - Jan, flex, $1,600/ mo+sec dep, Ruth, 526-6730, 526-2007 - LAFAYETTE, furn studio, $875+dep, 600 sq ft, priv ent/park, rustic,

quiet, safe, incl util, nr LBL, no smok/pets, george.craig@ comcast.net,

(925) 943-2179

NORTH BERKELEY, b&b home, breakfast daily, lovely furn rms, $650/mo, Helen, 527-3252 - NORTH BERKELEY, fully furn 1 bdrm, garden cottage, ~ 500 sq ft,

skylights, tile flrs, light, sunny, clean, sm upstairs bdrm w/ view

of hills, gated priv ent, close to bus/BART, bike path, walk to

Solano/ Monterey Mkt, avail mid-Sept, 1-yr lease pref, $1,350+util,

$2,050 dep, no smok, pets possible, Janet, 527-0210, [email protected]

NORTH BERKELEY HILLS studio, sunny, quiet, priv, garden setting, hardwd flrs, kitchen w/ gas stove, bthrm w/tub, dressing room, laundry fac, $825/mo+last mo+cleaning dep, mo-to-mo, 1 pers only, no pets/smok, Mrs Wurth, 527-5505, after 1:30 pm, [email protected] - NORTH BERKELEY HILLS, lge rm, 400 sq ft in priv home, fully furn

incl towels, linens, TV/VCR, priv deck & ent, share kitchen

& bth, quiet, nr campus/Lab, view, garden, $700/mo incl util,

avail 9/15 or possibly sooner, no smok, Carolyn, 549-0648, [email protected].

OAKLAND HILLS, quiet, sunny, 2 bdrm house, safe neighborhood, recently remodeled w/ new carpet, paint, heater, jacuzzi, lge kitchen, indoor laundry closet, sm wooden deck w/ patio area, dbl car garage, storage space, nr Lab, $1,450/mo+1st+last mo+dep, Kasia, (925) 639-5299, (925) 673-5029 - PIEDMONT, 1 lge 11’x17 furn bdrm with a priv bthrm, quiet,

scenic neighborhood, full access to kitchen, laundry rm, 1 space

in garage, $575/mo incl util, 1-yr lease, avail now, Peggy, 547-4351,

Weilun, X4079

SOUTH BERKELEY, AAA furn studio apt w/ full indep kitchen & bthrm in nice house, lge backyard, sep ent, shared w/d, free wireless access to DSL, util pd, $790 neg, nr UC/BART/shop, Lori or Tim, 883-0853 - TARA HILLS, 2 bdrms in 4 bdrm/2 bth house, share w/ a female, $650/mo, avail 10/01, Liz, X2724, cell, 685-0005, [email protected]

- HOUSING WANTED

- FEMALE looking for house to share in Orinda/Lafayette/Moraga area

or similar peaceful, rural setting, no smok, quiet & responsible,

Christina, 865-0863, [email protected]

VISITING PROFESSOR & family from Switzerland looking for 2+bdrm apt or house in or around Berkeley, 11/04 until 2/29/05, no pets, allergic to cats, stefanie. [email protected], tel ++41-1-633 43 37, fax ++41-1-632 11 89 - FREE

- DINING ROOM TABLE & CHAIRS, coffee table in bright solid colors, can deliver, Peter, 601-8052, X5931

- MISC ITEMS FOR SALE

- CHEST BED, 3 drawers, unfin, from Gorman’s, fits twin mattress, $50, Peter, 601-8052 or X5931

- CHROME BAR STOOLS, 2, w/ blk removable vinyl cushions, foot rings

on stools, exc, cond, $45, Lorri, X7493

DRESSER, Lane, beige lacquer w/ gold accents, $150; Stanley wood dining rm set, 6 chairs, 2 leaf ext’s, $300, Sue, 595-7123 - ELECTRIC LIFT CHAIR/RECLINER, Pride TMR-58, green, w/ heavy duty

lift actuator, exc cond, $380, Ron, X4410, 276-8079.

ROOF RACKS, Yakima, 48” bars 2, rain-gutter-type towers w/ locks 4, outfitted w/ kayak holder, $75, Susan, X4202; Bill, (916) 803-1616 - SF OPERA TICKETS, balc pair, 2nd row center, La Traviata, Sat eve, 9/18, $124/pair, Paul, X5508, 526-3519

Flea Market Policy

Submissions must include name, affiliation, extension, and home phone. Ads must be submitted in writing (e-mail: [email protected], fax: X6641,) or mailed/ delivered to Bldg. 65. Email address are included only in housing ads.

Ads run one issue only unless resubmitted, and are repeated only as space permits. The submission deadline for the September 17 issue is Thursday, September 9.

People, AWARDS & HONORS

EETD’s Levine Named to Clean Energy Board

Mark Levine

Mark Levine, director of the Lab’s Environmental Energy Technologies Division, has been named to the board of the recently formed California Clean Energy Fund (CCEF). The group will make equity investments totaling at least $30 million in emerging clean energy technology companies.

Six Lab Researchers Receive ACS Awards

Six Berkeley Lab scientists have received American Chemical Society (ACS) national awards for 2005: Paul Alivisatos (ACS Award in Colloid and Surface Chemistry), Jeff Long (National Fresenius Award), Peidong Yang (ACS Award in Pure Chemistry), Stephen Leone (Peter Debye Award in Physical Chemistry), Enrique Iglesia (George Olah Award in Hydrocarbon or Petroleum Chemistry), and Luciano Moretto (Seaborg Award for Nuclear Chemistry).

Lab Postdoc Receives Rett Syndrome Grant

Mizue Hisano, a post-doctoral researcher with life scientist Terumi Kohwi-Shigematsu, has been awarded a $100,000 grant from the Rett Syndrome Research Foundation. Hers is one of 15 projects funded for research to accelerate treatment and find a cure for the neurological disorder Rett Syndrome.

Hellman Family Faculty Fund 2004

Five Berkeley Lab scientists who serve as junior faculty members at UC Berkeley were among the 14 recipients of awards from the Hellman Family Faculty Fund. Established in 1995, the fund provides research support up to $50,000 to assistant professors who show promise for great distinction in their fields.

The Berkeley Lab recipients are: Matthew Francis of Materials Sciences for “Modified viral capsids as targeted delivery vectors for anticancer agents”; Jay T. Groves of Physical Biosciences for “Surface chemistry on cell membranes”; Alessandra Lanzara of Materials Sciences for “Unlocking the mystery of materials at the nanoscale by enhancing the investigation of electronic structure”; Song Li of Life Sciences for “Engineering of functional muscle in vitro using mesenchymal stem cells and micropatterned polymers of engineered tissues and biomaterials”; and Isha Ray of Environmental Energy Technologies Division for “From wells to well-being? Water for women in the developing world.”