Pier Oddone Wins 2005 Panofsky Prize

Shares Campaign is Back

Pier Oddone Wins 2005 Panofsky Prize

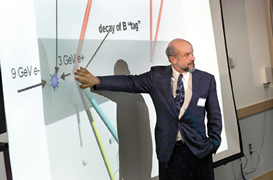

It was the idea of Berkeley Lab Deputy Director Pier Oddone that colliding beams of electrons (e-) and positrons (e+) at unequal energies would give scientists a way to measure the asymmetric decay of B particles. For this idea, Oddone won the 2005 Panofsky prize in experimental physics.

Pier Oddone, deputy director of Berkeley Lab, has won the 2005 W. K. H. Panofsky Prize in experimental particle physics for his conception of the asymmetric B factory. Awarded by the American Physical Society (APS), the Panofsky Prize is considered one of the highest honors a physicist can receive. Oddone was one of five Berkeley Lab scientists to win or share a 2005 APS award or prize.

The Panofsky Prize could not have gone to a more deserving individual, according to Berkeley Lab director Steve Chu.

“I am delighted that Pier’s contributions to high energy physics, in particular his initial proposal and leadership in the conceptual design of an asymmetric B factory, have been recognized by the Panofsky Prize,” Chu said. “As I have gotten to know Pier, I’ve learned that he’s not only an original as a particle physicist, but a deep scientist with broad interests and knowledge. In addition to his talents as a scientist, he is an extraordinary science manager and a wonderfully warm person.”

Established in 1985 to honor the former director of the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC), the W. K. H. Panofsky Prize comes with a $5,000 cash prize and a citation-bearing certificate. The citation on Oddone’s award reads: “For his insightful proposal to use an asymmetric B factory to carry out precision measurements of CP violation in B-meson decays, and for his energetic leadership of the first conceptual design studies that demonstrated the feasibility of this approach.”

Oddone’s idea for the B factory is being used to address one of the greatest mysteries in physics today: the very presence of our universe. If the Big Bang theory of creation and the Standard Model of physics are true, then, in the aftermath of the vast explosion that started it all, the released energy should have congealed into equal or symmetric amounts of matter and antimatter. These mirror-image particles should have quickly annihilated one another, creating a universe void of stars, planets and us.

The B factory at SLAC, Pier Oddone's brainchild, is being used to address some of the most puzzling mysteries in physics today.

Not only was this not the case, but the universe today is essentially absent of any antimatter, save for the tiny bits created in particle accelerators. From out of the Big Bang there must have emerged a preference for matter, but was this preference a lucky accident or the product of a natural asymmetry that tipped the scales in favor of matter? Physicists believe the answer lies in an asymmetry that arises from fundamental differences in the way unstable particles of matter and antimatter “decay” or break down into other, more stable particles. Thanks to Oddone’s vision, they now have an accelerator to test these differences.

At a workshop on the UCLA campus in 1987, while he was director of Berkeley Lab’s Physics Division, the Peruvian-born, MIT- and Princeton-educated Oddone suggested that the best way to look for asymmetry between matter and antimatter would be to collide beams of electrons and their antimatter counterparts, positrons, that were not of equal energies. This represented a radical break with tradition, in that electron-positron colliders had always been designed to smash together beams of equal energies.

Oddone argued that asymmetric collisions of electron and positron beams would make it possible to study a breakdown in matter/antimatter symmetry known as “CP violation.” The study could be done through measuring the decay of a rare particle that is itself a mix of matter and antimatter. This particle is called the B meson.

“We developed the concept of the asymmetric B factory by a combination of inspiration and perspiration,” Oddone once said. “The initial idea was more like a flash … gee, if we could collide asymmetrically then … But colliding asymmetrically with a high rate of events is tough.”

From out of that workshop came the “Asymmetric B factory” at SLAC, a $177-million joint collaboration between SLAC, Berkeley Lab, and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. The term “factory” comes from the machine being designed to produce millions upon millions of B mesons, and their antimatter counterparts, which are called B-bar mesons.

At SLAC’s B factory, a beam of electrons at an energy of 9 GeV (billion electron volts) and a beam of positrons at 3.1 GeV collide,

creating an “upsilon 4S” particle which immediately decays into B and B-bar mesons. Within two trillionths of a second, these matter/ antimatter B particles themselves decay into a menagerie of other charged and neutral products. Because of the imbalance in the energies of the colliding beams, the B particles are carried downstream in the direction of the higher energy beam, a forward motion that separates B and B-bar mesons, allowing scientists to observe possible inequities in their decay that favor matter over antimatter.

“The fact that the B and B-bar mesons are themselves decay products of the upsilon 4S in a well-defined quantum state allows us to use neat tricks to identify the B and B-bar mesons individually,” Oddone said when the B factory, and its massive detector system, BaBar, first began yielding data. “We can study a wide array of B and B-bar decay channels independently and measure any differences in their respective rates.”

In its six years of operation, the B factory has exceeded all expectations. In August of this year, B factory scientists released new measurements that revealed a difference in the decay rates of B and B-bar mesons as large as 13 percent. This direct observation of CP violation was hailed by Office of Science Director Ray Orbach as “a great scientific achievement,” and was called a “significant step toward solving the puzzle of matter versus antimatter” by SLAC director Jonathon Dorfan.

Oddone is the third Berkeley Lab physicist to win the Panofsky Prize. David Nygren won in 1998 for his conception of the time projection chamber (TPC) particle detection system, and Gerson Goldhaber shared the 1991 prize for his discovery of charmed mesons.

Lab Scientists Win Five APS 2005 Prizes

The American Physical Society was founded in 1899 “to advance and diffuse the knowledge of physics.” Today, the organization has more than 40,000 members, publishes some of the word’s most prestigious and widely read research journals, conducts a bevy of national and regional meetings, and recognizes professional accomplishment with prizes and awards. This year, in addition to the Panofsky prize won by Deputy Lab Director Pier Oddone (see main story), Berkeley Lab scientists won or shared four other of the 2005 APS awards, which are judged by a select panel of other physicists.

Here are the four other winners, their prizes, and citations:

David Chandler of the Chemical Sciences Division won the Irving Langmuir Prize in Chemical Physics “for the creation of widely used analytical methods and simulation techniques in statistical mechanics, with applications to theories of liquids, chemical kinetics, quantum processes, and reaction paths in complex systems.”

Roger Falcone of the Advanced Light Source shared the Leo Szilard Lectureship Award for his participation in an APS study group on Boost-Phase Intercept Systems for National Missile Defense, which “produced a report that adds physics insight to the public debate.”

Ramamoorthy Ramesh of the Materials Sciences Division won the David Adler Lectureship Award “for his contributions to materials physics that have enabled a deeper understanding of ferroelectric materials, the discovery of colossal magnetoresistance, and leadership in communicating the excitement of materials physics to a broad audience.”

Yuri Suzuki of the Materials Sciences Division won the Maria Goeppert-Mayer Award “for her research in epitaxial oxide thin films, nanostructures and devices with tailored magnetic, electronic and optical properties.”

SHARES CAMPAIGN IS BACK

Helping People One Donation at a Time

Sometimes a little help goes a long way, especially for an elderly Berkeley woman confined to a wheelchair. The homemade ramp she used to access her house was old, rickety, and too steep to be easily climbed. She and her frail husband needed something better if they were to continue to live independently, but they couldn’t afford to make their own improvements.

Then along came Rebuilding Together, which provides free home repair for low-income seniors and people with disabilities. With donated supplies and help from a local building contractor, the charity installed a strong new ramp with handrails. Now, the woman can come and go with ease, and the couple can live without assistance or fear of an accident.

“They can continue to live on their own. This is just one of the many projects we’ve undertaken in the past few months,” says Jill Davis, executive director for the local Rebuilding Together affiliate that serves Albany, Berkeley and Emeryville. Since 1991, her organization has worked on 376 homes and 106 facilities. Some jobs are small, like cleaning moldy apartments. Others are big, like rebuilding an Albany woman’s home that nearly burned to the ground. But they all improve people’s lives, and they all depend on donations.

Beginning Monday and through Nov. 24, Berkeley Lab employees will have the opportunity to donate to Rebuilding Together or any agency designated as a tax-exempt IRS 501(c)(3) through a program called SHARES, for Science for Health, Assistance, Resources, Education and Services. The campaign, now entering its seventh year, supports Berkeley Lab’s commitment to reach out to surrounding communities and help organizations that depend largely on donations.

“Thank you to those who have given generously in past years’ drives,” says Lab Director Steve Chu. “Lab employees contributed more than $100,000 during our best campaign, a significant sum when I know that you are often urged to give to many other worthy causes. Please consider helping Berkeley Lab fulfill its responsibility as a good corporate citizen while helping to make our communities better places to live, learn and grow.”

Over the next few days, Berkeley Lab employees will receive a packet in the mail that outlines the donation process and lists 13 local charities dedicated to science and education outreach. These include agencies that give struggling students a boost, such as Project SEED, which helps elementary and middle school children improve their math skills. Other charities expose children to the wonders of science and its job opportunities, such as Berkeley Biotechnology Education, Inc., which creates partnerships between industry and schools to teach students about careers in biotechnology.

Berkeley Lab will host a charity fair on Tuesday, Nov. 16 from 11:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. at the cafeteria to give employees a chance to learn more about these charities.

Donors can also commit contributions through a web-based format created by Community Health Charities, which will act as the disbursement agent for donations. This fully secure and user-friendly website (https://healthcharitiescal.org/) will allow employees to select charities, choose a method of payment — payroll deduction, check or credit card — and disburse funds among the charities.

Employees who have a favorite charity that is not included in the list can still donate through the donor choice write-in option on the donor form. All donations are tax deduct-ible. One-time gifts by check will be applied to year 2004 tax returns, while the payroll deduction option will take effect on Jan. 1 and will apply to tax year 2005.

‘What’s Next’ Expo Reaches out to Future Scientists

Genomics Division researcher Elaine Gong (above, left) helped young people from the Chicago area learn the art of DNA extraction during the first “What’s Next” Expo held on Oct. 14 at Chicago’s Navy Pier. Berkeley Lab and the JGI were among dozens of DOE-funded programs participating in the event, which attracted more than 500 seventh- and eighth-grade students and their teachers. The Expo was designed to showcase the latest cutting-edge scientific and technological advances as a means to encourage students to pursue future careers in math and science

Popular Lab People Mover is a Good Sport

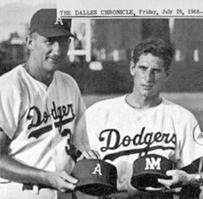

Lab bus driver Ralph Sallee now (above left), and in 1968 (above right), when he joined the Albuquerque Dodgers, with Dodger manager Roger Craig.

To say Ralph Sallee (pronounced sal-LEE), a lead driver for the Lab’s shuttle service, has dabbled in a number of arenas during the course of his life is an understatement.

He started out as a farm boy, growing up on a wheat and cattle ranch in Oregon, joined the Air Force and learned how to operate heavy equipment, was signed by the Dodgers as a pitcher, then later coached women’s high school basketball in the wilds of Alaska for 24 years.

He has spent the last 10 years moving employees and guests up, down and around the Hill. And during off hours, Sallee can most likely be found on a local golf course.

“I’ve had many different experiences over the years,” he says, “but sports has always been a big part of my life.“

Throughout childhood, Sallee played baseball and basketball. As a young man, while stationed at an Air Force base in Roswell, NM, he played baseball for a city league. He was spotted by a recruiter for the University of New Mexico and was offered a full scholarship. After graduating, he was signed as a free agent by the Los Angeles Dodgers.

“I never did make it to the big show, though,” Sallee recalls. “I was playing for the Albuquerque Dodgers, in the Texas League, but severe bursitis in my shoulder and elbow ended my career.”

Determined to keep sports a part of his life, he used his teaching degree and athletic know-how to garner a job as an industrial arts teacher and coach of the women’s basketball team at a high school in Palmer, Alaska.

After 24 chilly years up north, Sallee and his wife Nancy decided to retire in the Bay Area.

“Nancy, who was also an educator, had previously attended some teacher-training courses at the Lab’s Center for Science and Engineering Education, and really liked it here,” Sallee says. “And I figured I could spend my golden years as a golf bum.”

But the life of leisure didn’t suit Sallee that well. Nancy procured a job at the Lab (she now works for the Advanced Light Source) and suggested her husband apply for a position as a shuttle bus driver. The rest, as they say, is history.

Sallee’s laid-back manner, attention to detail, and concern for the safety of his riders has made him a favorite among the Lab’s passengers, and prompted his promotion to lead driver about four years ago.

“I just try to make it as easy as possible for the passengers to get where they’re going in a timely manner,” he explains. “Roadwork, traffic, and safety issues can sometimes cause inconveniences, but virtually all of the passengers I pick up are nice and appreciative of the work we do.”

SAMOA’S GIFT TO THE WORLD

Ancient indigenous medicine may lead to anti-AIDS drug

By Lynn Yarris

Jay Keasling, a chemical engineer at the forefront of the emerging field of synthetic biology, wants to use E. coli bacteria to synthesize genes from mamala trees like this, which produce a promising anti-AIDS drug.

In 1987, on the Samoan island of Savaii, what is now known as the Falealupo Rain Forest Preserve was about to be clear-cut out of existence by a logging company, and along with it, a small tree, known to the natives as the mamala tree and to botanists as Homalanthus nutans. An ethnobotanist named Paul Alan Cox saved the mamala trees and their forest. And now, if all goes according to plan, the research of Jay Keasling, who heads the Synthetic Biology Department for Berkeley Lab’s Physical Biosciences Division, will give AIDS victims all over the world cause for celebration.

Working through Keasling, a UC Berkeley professor of chemical engineering, UC Berkeley recently signed a landmark agreement with the Samoan government to isolate the gene for prostratin, a chemical compound contained in the bark and stemwood of the mamala tree that holds enormous therapeutic potential as an anti-AIDS drug, and to share any royalties from the sale of a gene-derived drug with the people of Samoa. Under this agreement, Keasling and his research group will seek to genetically engineer a strain of E. coli bacteria that can cheaply synthesize and mass-produce prostratin.

“A microbial source for prostratin will ensure a plentiful, high-quality supply if it is approved as an anti-AIDS drug,” Keasling says. “I think this agreement with the Samoan government could set a precedent both for biodiversity conservation and for genetic research by including indigenous peoples as full partners in royalties for new gene discoveries that result from their ancient medicines.”

This story begins with Cox, now the director of the Institute for Ethnobotany at the National Tropical Botanical Garden in Hawaii. Ethno-botanists study the ways in which indigenous cultures use plants for medicine, which is why in 1987 Cox was sitting in a thatched hut with an elderly Samoan woman named Epenesa Mauigoa. A tribal healer, she was describing for him the 121 herbal remedies she knew. Cox became particularly interested in remedy number 37, which called for boiling the bark from the mamala tree and giving the liquid to those suffering from what Samoans called fiva sama sama, and we know as viral hepatitis.

Cox sent samples of remedy number 37 to the National Cancer Institute and in 1992 NCI researchers identified prostratin as the active ingredient in the mamala bark. They found that it was indeed an effective treatment for hepatitis and also had powerful and unique therapeutic effects against AIDS. Not only did prostratin prevent the AIDS-causing human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) from infecting human cells, it also forced dormant HIV virus particles out from hibernation within human immune cells, where they are protected from virus-killing medicines.

Today’s best anti-AIDS drugs can reduce a patient’s HIV populations to safe levels, but as soon as the patient stops taking the drugs, dormant viruses emerge from their immune cell sanctuaries and quickly restore HIV populations to dangerous levels. Prostratin flushes out these “viral reservoirs” so that anti-AIDS drugs can eradicate the HIV population entirely. What’s more, unlike other compounds from the same chemical family, which have been known to promote the growth of cancerous tumors, prostratin was shown to be a tumor suppressor.

Members of a Samoan villege council listen to a PowerPoint presentation given in their language describing how genetic material from their mamala tree and synthetic biology techniques could bring them revenue without endangering their rain forest. The presentation was projected onto a white sheet hung in an open air village hall.

The Samoan people and UC Berkeley will get equal shares of any commercial proceeds from the prostratin gene sequence. Samoan revenues will go to the government and to the villages and families of healers who discovered prostratin.

Preserving the mamala tree population in Samoa was a critical first step, but there is still a crucial need to mass-produce prostratin in quantities far beyond what the bark and stemwood of the trees could supply. Enter Keasling and his synthetic biology research group, who opened the door to adding new genes to E. coli bacteria by creating an E. coli strain with a new and specially designed metabolic pathway.

Prostratin is a member of the huge isoprenoid family of chemical compounds, which are used in a wide variety of applications including anti-cancer and antimalarial drugs. Genetic control mechanisms within the E. coli’s natural metabolic pathway would interfere with the bacteria’s ability to synthesize isoprenoid compounds, but Keasling and his colleagues get around this barrier by giving their E. coli strain a second metabolic pathway derived from yeast. This alternate pathway can be used to transform the E. coli into living factories designed to mass-produce a desired isoprenoid.

Keasling and his research group first used their engineered strain of E. coli to produce a precursor to arte-misinin, one of the most promising of all the anti-malarial drugs (see the View, March 19, 2004.) The success of this work led Keasling to Cox and his work with prostratin. Artemisinin and prostratin both belong to the terpene class of isoprenoids.

“The basic superstructure of the bug we engineered to produce the antimalarial drug will work for producing prostratin,” says Keasling. “Of course, we will need to add a few additional genes, but having the basic structure in place will save us both time and money.”

Keasling and Cox traveled to Samoa this past August and met with the leaders of three Samoan villages where the mamala tree grows.

“We gave a PowerPoint presentation in the Samoan language to the councils of the three villages, and then to the Samoan federal government,” Keasling says. “UCB was very generous in sharing 50 percent of any royalties received on the genes from the mamala tree. Since in this particular case the Samoan healers are actually the inventors, it is only right that they receive a large fraction of the royalties for their invention.”

The agreement was announced on Sept. 30 in Apia, the capital of Samoa. It recognizes Samoa’s assertion of national sovereignty over the gene sequence of prostratin and the intellectual contribution of the healers of Samoa. Any proposed licensing agreement between the university and a pharmaceutical company using the results of Keasling’s research will require the company to make the drug available in the developing world at “very nominal profit.”

In addition to the enormous potential medical benefits to be realized from the use of E. coli to mass-produce prostratin, Keasling sees enormous potential ecological benefits as well.

“If prostratin makes it through clinical trials and is used to treat HIV-AIDS, the ensuing demand could lead to a clear-cutting of the rain forests that contain the trees,” he says. “By producing the drug in bacteria, we save the rain forests from clear cutting, and the Samoans will get money from the engineered bug without having to do anything detrimental to their environment.”

Ion Beams Wield a Sharper Scalpel Carving New Niches for Focused Ion Beams

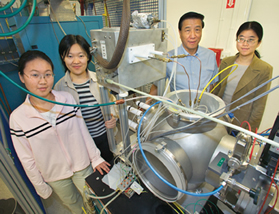

Ye Chen, Lili Ji, Ka-Ngo Leung, and Qing Ji with test apparatus for the combined electron/positive-ion beam device.

From Ka-Ngo Leung’s Plasma and Ion Source Technology Group in the Accelerator and Fusion Research Division comes a new way to create focused ion beams, promising to greatly extend the reach of this important technology.

Focused ion beams are widespread in the semiconductor industry where, among other applications, they are used to carve nanometer-scale structures, repair defects in photolithography masks, analyze integrated circuits, and dope semiconductors. Focused ion beams are handy in many other fields as well, including chemical analysis, structural biology, surface imaging, patterning thin films for magnetic storage, and micromachining miniature medical implants.

Complicating these applications, however, is the fact that ion beams — charged particles by definition, usually positively charged atoms — encounter serious problems when they are aimed at a nonconducting target.

When a positive ion beam is aimed at an insulating sample, trouble arises because “the target material is charged by the positive ions,” explains Qing Ji, a guest in Leung’s lab who is a postdoctoral fellow in the Center for Imaging and Mesoscale Structures at Harvard University. “As the positive charge builds up on the sample it repels the ions and defocuses the beam.”

Ji and her Berkeley Lab colleagues Leung, Lily Ji, and Ye Chen overcame this problem by devising a system that simultaneously combines focused beams of ions and electrons, enabling the negatively charged electrons to balance the positively charged ions.

Traditionally, two methods have been used to keep a nonmetallic sample from acquiring charge from a positive-ion beam, Qing Ji says. “One method is to pass the beam through a gas cell, where it is partially neutralized before it reaches the sample by acquiring electrons from the gas. The other is to train a separate beam of electrons on the sample.”

Top: A combined beam of electrons and positive ions is formed in a double-chamber plasma source.

Bottom: Ions generated by a plasma source can be extracted through astencil mask that contains apertures with different shapes, such as round holes, lines, or arcs (top), and in 3-D configurations as well (bottom).

Both have significant disadvantages. A gas cell may require too much distance between the beam accelerator and the sample, which can interfere with beam focusing. And a separate electron beam requires a separate accelerator, which must be precisely aligned with the ion beam at all times. When the ion beam is scanning over the sample this can be difficult; if multiple ion beamlets are being directed at the sample simultaneously, it’s virtually impossible.

“In fact our new beam system was inspired by one of our group’s previous inventions, a multiple-ion-beam system that can steer hundreds of beamlets simultaneously,” says Ji. “The device had no room for a neutralizing gas cell, and there was no way to use a separate electron beam to neutralize the sample.”

The group’s novel solution: instead of a conventional liquid-metal ion source, their system uses two chambers in which plasma is generated by radio-frequency electromagnetic fields, which separate gas molecules into their component electrons and ions. The two chambers are divided by an arrangement of electrodes that allows only high-energy electrons to exit the first chamber, keeping positive ions out.

The second chamber forms and accelerates an ion beam at a lower voltage, which does not impede the high-energy electron beam. Both beams combine in a single mixed beam and are extracted by the accelerator column. The mixed beam stays tight on its way to the target, because with electrons present the positive ions do not push one another apart, nor does it charge the sample upon striking it.

The combined-beam system can accelerate numerous species of ions, including noble gases like argon, metals like manganese, and even molecular ions like carbon-60 “buckyballs,” useful in biological studies because of their stability.

To demonstrate the versatility of their new imprinter, the researchers used stencil masks perforated with shapes like circles, lines and arcs as the forward electrode of the accelerator. The dimensions of the shapes could be altered dramatically by establishing an electrostatic field between the mask and the sample. The imprinter works with three-dimensional masks too — for example, cylindrical masks that accelerate surrounding electron and ion plasma to carve out features in a cardiac stent.

“Unlike the way cardiac stents are manufactured now — one at a time, machined by a laser — ion-beam imprinting would allow hundreds or thousands of stents to be produced with just one shot,” says Ka-Ngo Leung. Other current industrial uses that could benefit from imprinting with electron/positive-ion beams include “sound suppressors for jet engines that require millions of holes, which could be produced in one shot. Or cutting the many trenches needed to increase surface area in fuel-cell electrodes, which could also be done in one shot.”

Currently these and other industrial applications employ laser systems; the new combined electron/ positive-ion beam device offers an economical way to greatly increase efficiency and throughput.

“A combined electron and ion beam imprinter and its applications,” by Qing Ji and Lili Ji, Ye Chen, and Ka-Ngo Leung of AFRD and the Department of Nuclear Engineering at UC Berkeley, will appear in Applied Physics Letters in mid-November.

Another Reason to Hate Traffic

Lab scientists assist in study linking busy roads with children’s respiratory problems

Berkeley Lab contributed to a landmark study that links exposure to traffic pollutants with asthma and bronchitis symptoms in children

Berkeley Lab contributed to a landmark study that links exposure to traffic pollutants with asthma and bronchitis symptoms in children

Four years ago, Berkeley Lab’s Alfred Hodgson, Toshifumi Hotchi and Brett Singer gathered together some old metal cabinets and filled them with air pollution monitoring equipment. They trucked them to 10 East Bay elementary schools, placed them near basketball courts or just outside doorways, and left them running for weeks at a time.

The data they collected made headlines last week in the San Francisco Chronicle as part of a landmark study that links traffic-related pollution with respiratory problems in school children. The study, which was led by scientists from California EPA’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, found that children suffered moderately higher rates of asthma and bronchitis symptoms if they attended schools and lived in neighborhoods with higher levels of traffic pollution. Although several European studies have made this connection, it’s the first time such a link has been made in the U.S.

“There is a need to evaluate the impact of traffic pollution on children’s respiratory health in the U.S,” says Brett Singer, a scientist in the Environmental Energy Technologies Division along with Hodgson and Hotchi. “Our study provides valuable information that will help assess the health consequences of living so close to a freeway.”

It all started in 2000, when California EPA asked Berkeley Lab to partner with them and head up the air-monitoring phase of the epidemiological study. The East Bay is an especially good place to conduct the study because it has relatively good regional air quality, and winds consistently blow from west to east throughout much of the year. Hodgson, Hotchi and Singer filled 10 office cabinets with enough monitoring equipment to measure the airborne concentrations of several pollutants emitted by cars and diesel trucks, such as particulate matter, black carbon, and nitrogen oxides.

They installed these monitors at 10 elementary schools in Oakland, San Leandro and Hayward. Some of the schools are upwind of busy roads, some are within 300 meters downwind, and some are far downwind. Because most of the students live in neighborhoods near their schools, school locations were assumed to be representative of the children’s overall exposure to traffic pollutants. The Berkeley Lab researchers then measured the pollution concentrations at each school over an 11-week period in the spring and an eight-week period in the fall.

“We examined two different seasons with different weather patterns. It enabled us to determine with a great deal of certainty the variations in pollution concentrations at the 10 schools,” says Singer. “Not surprisingly, schools close to and downwind from the freeway had higher levels.”

Meanwhile, California EPA scientists sent questionnaires to the parents of more than 1,100 students who attend the schools, asking about the children’s health and demographic information.

When the California EPA scientists paired the air pollution data with the health data, they found the prevalence of asthma and bronchitis symptoms were about seven percent higher in children from neighborhoods with higher levels of traffic pollutants compared with children who live far from busy roads. The study was published in a recent issue of the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

One Outstanding Performance Among Many

Outstanding Performance Awards honor exceptional contributions in science, administration, safety, even public outreach. But OPA winners have one thing in common: they go beyond job expectations to achieve exceptional results.

Daniel Kim Girlington says he’s the “troll who lives under the cyclotron.”

Daniel Kim Girlington of the Facilities Division personifies the awarness, forward thinking, and persistent effort that win OPAs. In four years at the 88-Inch Cyclotron he’s collected two of them, most recently for performing major electrical corrections while keeping the cyclotron running, resulting in substantial savings.

Girlington, who calls himself “the troll who lives under the cyclotron,” says the venerable facility is in good shape, “but 40-year-old equipment has a tendency to wear out.” Repairs can be a challenge. After dozens of fixes that helped Building 88 pass OSHA inspections with excellent scores, Girlington determined to get to the bottom of a stubborn oil leak in the power transformers just west of the building.

“We knew we had a leak, but we didn’t know where it was going.” The answer turned out to be into the wireways beneath the concrete floor, where electrical cables sat in lost oil, their rubber insulation bubbling and shedding. Because the oil was contaminated with PCBs, the cleanup took special care.

The leak was in 40-year-old current feed-through plugs resembling spark plugs — right down to their Autolite labels. But Autolite hadn’t made them for 20 years and didn’t know who did. By luck and persistence, Girlington tracked down Douglas Electrical Components, Inc. in New Jersey and bought 20 of the rare devices.

Elsewhere in the facility, leaking PCB-contaminated oil from the hydraulic ram that opens the shielding’s vault doors had caused “a spiderweb of eroded wiring” under the floor of the adjacent helium-compressor room. At the first hint of the problem, management decided to reroute all the wires.

Girlington worked continually to identify each wire as it was dug up, simultaneously reconnecting the corresponding new wires overhead. A project estimated to have put the cyclotron out of commission for two extra weeks was completed during the normal maintenance shutdown, saving time and tens of thousands of dollars.

November through June were months with a constant stream of matters urgently needing Girling-ton’s attention, but “there are times when you’re in the flow, working hard at top performance,” he says. For Girlington’s peak performance, Building 88 Manager Dennis Collins suggested him for this year’s OPA — the kind of performance in any field of endeavor that calls for recognition.

New Class of OPA Recipients Honored

Fifty-eight exceptional Lab employees were recently recognized with Outstanding Performance Awards, or OPAs, as they are commonly known. The most recent class of OPA recipients was honored at a reception hosted by Lab Deputy Director Pier Oddone on Oct. 7.

The awards are granted both to individuals and to members of teams three times a year for “significant one-time achievements in pursuit of the accomplishment of labwide objectives above and beyond regular job expectations.” Managers and supervisors are invited to nominate employees, based on what is described as “exceptional, outstanding” effort that surpasses performance goals.

| Full Name | Home / Matrix Division |

|---|---|

| Susan Aberg | BSD/OPS |

| Christopher G. Campbell | ESD |

| Robert K. Cheng | EETD |

| Bernadette B. Dixon | BSD/ALS |

| Angela A. Gill | BSD/CSD |

| Daniel Kim Girlington | FAC |

| Charles A. Goldman | EETD |

| John Joseph | ENG |

| David Malone | BSD/ALS |

| Kimberly A. Martens | OPS |

| Benjamin Ortega | HR |

| Peidong Yang | MSD |

| Alex K. Zettl | MSD |

| William S. Tiffany | ENG |

| Robert D. Shannon | ENG |

| Don B. Lester | ENG |

| Jeffrey K. Trigg | ENG |

| Thomas Perry | ENG |

| Center for X-Ray Optics’ Engineering Team | |

| Kevin M. Bradley | ENG |

| Paul E. Denham | ENG |

| Brian Hoef | ENG |

| Michael S. Jones | ENG |

| Charles D. Kemp | ENG |

| Ronald M. Oort | ENG |

| Farhad Salmassi | ENG |

| Rene Delano | ENG |

| Albert W. Rawlins | ENG |

| Kenneth D. Woolfe | ENG |

| Hanjing Huang | ENG |

| Robert F. Gunion | ENG |

| Senajith B. Rekawa | ENG |

| Core Email Server Reduction Team | |

| James E. Lee | ITSD |

| Martin Gelbaum | ITSD |

| Jack E. Krouse III | ITSD |

| EPB Hall Demo team | |

| Margaret R. Goglia | FAC |

| John Patterson | FAC |

| Richard C. Stanton | FAC |

| ITSD Challenge Team | |

| Mark T. Dedlow | ITSD |

| Charles E. Verboom | ITSD |

| Ted G. Sopher | ITSD |

| Jeffrey R. Willer | ITSD |

| NFACS Proposal Team | |

| David H. Bailey | CRD |

| John A. Hules | ITSD |

| Leonid Oliker | CRD |

| William C. Saphir | NERSC |

| John M. Shalf | CRD |

| Transition Metal Electrochromics Team | |

| Thomas J. Richardson | EETD |

| Johnathan L. Slack | EETD |

| Balanced Scorecard team | |

| Rosemary Lowden | ITSD |

| Carla H. Garbis | BSD |

| Cynthia C. Coolahan | BSD |

| Sherri L. Harding | BSD |

| Gary H. Zeman | EHS |

| Michele A. Mock | BSD |

| TRU Waste Shipment Team | |

| Nancy E. Rothermich | EHS |

| James M. Gambrell | EHS |

| Ilham Al Mahamid | EHS |

| Barry M. Freifeld | EHS |

Flea Market

- AUTOS & SUPPLIES

- ‘99 Toyota Camry LE, 4 dr, V6, all pwr, ABS, cruise, ac, 64K mi, am/fm/cd, 6 speakers, exc mech cond, maint rec’s, one owner, bronze, immaculate, like new $9,700, Susan, X6507, (707) 647-1409

- ‘93 Mercury Villager LS Minivan, 140K mi, all pwr, abs, am/fm/cass, ac, roof rack, cruise, privacy glass, clean, runs great, 7 seats, Hans, X4895, 486 1914

- HOUSING

- BERKELEY HILLS, bay view, furn room 17’x15’, priv ent, own bthrm, quiet neighborhood near UC/pub trans/shops, cooking facil in adj rm, pool table, workout mach, w&d, $850/mo incl linens, dishes, util, phone, DSL, no smok/pets, short stays $300/wk, Carol, 524-6692

- EL CERRITO HILLS, spacious studio, $850, fully furn studio, kitchenette w/ new appl, all util incl, free cable TV & laundry, 15 min to UCB, parking, walk to El Cerrito Pl, 7613 Errol Dr, Voya, 525-8211

- FAIRFIELD, 3-yr-old home, 3 bdrm/2.5 bths, 1,600 sq ft, hardwd flrs, tile floors, granite countertops, w/d hookup, avail now, $1,595/mo, dep $1,595, Jeff, (916) 723-5111

- KENSINGTON, furn rm avail for visiting staff, own 1/2 bth, view, kitchen & laundry avail, $550/mo, Ruth, 526-2007, 526-6730

- OAKLAND duplex, 1640 & 1642 12th St, 4 bdrm/1 bth, 1,500 sq ft, new appl, tile flrs & countertops, w/d hookup, avail 10/15, $1,850/mo downstairs, $1,950/mo upstairs, dep $1,850 or $1,950, Rina, 232-1104

- OAKLAND, Glenview, 2 bdrm/1 bth apt, downstairs inlaw unit, sep ent, priv & peaceful garden setting, liv rm w/ built-in shelves, French dr to sunny patio, 2nd smaller bdrm/office, gallery kitchen, new carpet, great neighborhood, nr shop/bus/carpool no/smok/pets, some furn avail, $1,150/mo + some util, [email protected]

- OAKLAND/Lake Merritt, sublet avail Feb-July ‘05, 2 bdrm/1 bth, fully furn, 2nd bdrm used for storage, incl parking, laundry rm, pool, water & garbage, nr BART, shops, $1,100/mo, Michelle, 325-8604 cell, [email protected]

- ROCKRIDGE, 3 bdrm/2 bths furn house, avail 1/01/05, 7/4/05, free DSL, newly-remodeled kitchen, hardwd flrs, formal din room, w/d, fp, yard, priv patio, pictures: http://raw.cs.berkeley.edu/house, nr UCB, Lab, $2,300/mo, Simona, 653-1623

- VALLEJO, 1 yr old Townhouse, 4bdrm, 1.5 bth, 1,700 sq ft, yr old appliances, w/d hookup, avail 11/15, $1,795/mo, dep $1,795, Cori, 205-6533

- WEST OAKLAND, 3645 West St, fourplex, 3 bdrm/1 bth, 1,200 sq ft, new tile flrs & countertops, new bthtub/shower, w/d hookup, nr MacArthur BART/pub trans, avail now, $1,600/mo, dep $1,600, Rina, 232-1104

- HOUSING WANTED

- VISITING POSTDOC, male, nonsmoker needs accommodation 11/6 to 12/30, [email protected], X6512

- MISC ITEMS FOR SALE

- BICYCLE, cruiser, 2003 Raleigh Retro AL7, blue, rode once, $225, Carol, X6227

- CAMERA, Nikon N60, AF zoom, 35-80 mm, f/4-5.6D, perf cond, used once, $150, Tennessee, X5013

- DESK, mission-style oak w/ 2 drawers, $350; color printer, never used $25; black 2-drawer filing cabinet $25; oak desk chair, $50; leather/chrome swivel chair $75; metal flr lamp, $50; CD holder for ~60 CDs, $45; assorted rugs $25-50; pots & pans, kitchen utensils, pottery, $2-10, Susan, X5437 or 845-1697

- ELECTRIC LIFT CHAIR/RECLINER, pride model TMR-58, green, w/ heavy duty lift actuator, exc cond, $330, Ron, X4410, 276-8079

- MATTRESS, queen sz + box set w/ metal movable frame under bed $60; kid car seat, good cond, $12; baby cribs + mattress, very good cond $60; old-style lady bike, $15; boy’s bike, $10; games table, small pool, ping pong, chess, etc, $30, (925) 296-5760, 841-2140

- PING 380 ladies graphite driver, 12°, light performance, used only 3 times, $200/bo, Nancy, X5467, 215-1009

- PRINT CARTRIDGES, HP 29 & 49, new, fresh, $10 ea, Bill, X5632, 925-935-5004

- REFRIGERATOR, Hotpoint 15 cu ft, white, immaculate, 2 months old, $195/bo, Ian, 644-1272

- RICE COOKER, Sanyo 5 cups, $10, Heelo, X6174

- ROOF AUTO CARGO CARRIER, lockable x-cargo model, x-large, 50”Lx38”Wx22”H, weatherproof, $35, Karl, X6129

- SF OPERA TICKETS, balc pr, 2nd row ctr, Sat eves, Flying Dutchman, 11/20, Eugene Onegin 11/27, $124/pair, Paul, X5508, 526-3519

- STEREO SYSTEM, Aiwa, 200 watts, twin duct 3 way bass reflex speaker syst w/ surround sound, dual cass decks, 3-disc player, sensor needs to be replaced, remote control, exc cond $80; futon, blk iron frame, dark blue futon cover, exc cond, $60, Mary, 638-1451

- TREADMILL, Proform 1hp. 0-12mph, power tilt, speed, dist, calories readout, folds, like new, $400/bo, Jim, X6058, (925) 284-2353

- FREE

- SOFABED, floral fabric/neutral colors, free if you pick up; note: sofa is not in pristine condition, comes with matching pillows, bed works beautifully, Susan, X5437 or 845-1697

- VACATION

- ENGLAND, 3 bdrm house on edge of small historic village in scenic valley, S.E. England, avail 12/04 to 6/05, flex, modest but comfortable, nice view, furn, DSL line, small garden, 20 min to Canterbury, easy access to Europe via Chunnel or ferry $1,500/mo, Jeanne, 843-3171

- PARIS, FRANCE, nr Eiffel Tower, furn eleg & sunny 2 bdrm/1 bth apt, avail yr-round by wk/mo, close to stores/rest/pub trans, 848-1830

People, AWARDS & HONORS

Charles Shank Wins DOE Gold Award

Former Lab Director Charles Shank is one of eight current and former directors of DOE national laboratories who were presented with the Secretary’s Gold Award. This is the Energy Department’s highest honorary award and includes a plaque with citation, a medallion and a rosette. Energy Secretary Spencer Abraham handed out the awards on Oct. 25 at a luncheon at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C.

Former Lab Director Charles Shank is one of eight current and former directors of DOE national laboratories who were presented with the Secretary’s Gold Award. This is the Energy Department’s highest honorary award and includes a plaque with citation, a medallion and a rosette. Energy Secretary Spencer Abraham handed out the awards on Oct. 25 at a luncheon at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C.

“I’m proud to recognize the people whose hard work and dedication contribute so much to the Department of Energy’s vital missions,” Abraham said. “Our world-class laboratories are a marvelous resource and have made far-reaching contributions . . . The incredible work done in the laboratories is made possible by the strong, steady, and responsible leadership of these directors.”

The other recipients are Hermann Grunder, director of Argonne National Laboratory; William Madia, former director of Pacific Northwest and Oak Ridge National Laboratories; John Marburger, former director of Brookhaven National Laboratory; Lura Powell, former director of Pacific Northwest National Labor-atory; Bruce Tarter, director emeritus of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory; Richard Truly, director of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory; and Michael Witherell, director of Fermi National Accel-erator Laboratory.

“Dr. Tarter and Dr. Shank have demonstrated exceptional leadership in guiding their respective laboratories,” said UC President Robert C. Dynes. UC manages LLNL and LBNL for the DOE. “Both were strong and imaginative managers, and it is through their vision and guidance that their laboratories remain among the crown jewels of science and technology.”

Lab Scientists Accept ‘R&D 100’ Awards

Two prestigious R&D 100 Awards, announced earlier this year, have been officially awarded this month to Lab scientists Alex Zettl of the Materials Sciences Division and the team of Tom Richardson and Jonathan Slack

of the Environmental Energy Technologies Division. Pictured above is Slack (right), who also accepted the award on behalf of his colleague Tom Richardson, along with graduate students Adam Fennimore (left) and Tom Yuzvinsky, who accepted the award on behalf of Alex Zettl.

The R&D 100 Awards recognize the “100 most technologically significant new products and advancements over the past year.”

Zettl won his award for creating the “synthetic rotational nanomotor” — the smallest synthetic motor ever reported. Richardson and Slack were honored for developing a unique new type of energy-saving eletrochromic window with possible applications to glass windows in buildings, sunroofs, and even space missions. (For more on these technologies see the July 9, 2004 issue of the View.)

Thirty-four Berkeley Lab researchers have won R&D 100 Awards to date.