Cataloging

Airborne Bacteria, City by City: The good, the bad and the esoteric

Horst Simon Named Associate

Lab Director for Computing Sciences

Cataloging Airborne Bacteria, City by City

The good, the bad and the esoteric

BY DAN KROTZ

|

|

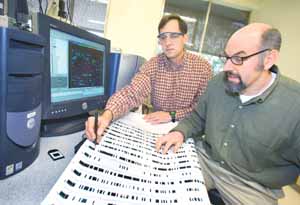

| No microbe goes unnoticed as Gary Andersen (left) and Todd DeSantis pore over reams of data that shed light on the nation's population of airborne bacteria. |

They’re finding botulism-causing bacteria in the air near Davis, Calif. In other cities, they’re finding Escherichia coli and cousins of the bacteria that causes anthrax. But they’re not alarmed. It’s all part of the first nationwide census of naturally occurring airborne bacteria, a $1 million study funded by the Department of Homeland Security and conducted by researchers at Berkeley Lab’s Center for Environmental Biotechnology.

Their goal is to catalog the thousands of types of bacteria drifting and swirling in the nation’s cities, and how each bacterium’s relative concentration changes week by week. When completed, the census will help researchers differentiate between natural and suspicious fluctuations in airborne pathogens, which can help deter false alarms. It will also help scientists refine tests that identify disease-causing bacteria.

”If you’re developing a way to test for harmful amounts of anthrax, you need to know the background levels of anthrax normally found in the air,” says Todd DeSantis of the Earth Sciences Division, who is conducting the research along with project leader Gary Andersen and scientists Jordan Moberg, Sonya Murray and Ingrid Zubieta.

Although deadly bacteria grab headlines because they can be used as a terrorist weapon, they are also our everyday neighbors. Botulism is caused by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, which is commonly found in the soil and the intestinal tracts of animals. And anthrax, which is caused by Bacillus anthracis, is an infectious livestock disease. Inevitably, some of these bacteria become aerosolized, meaning they float away in the slightest breeze, and usually in concentrations so small they remain harmless. Their only threat is to confound the search for potentially dangerous concentrations of bacteria, which is why it’s necessary to record everything that lurks in the air — the good, the bad and the esoteric.

The census relies on air samples culled from about 300 air monitors positioned in 30 U.S. cities and surrounding areas. This far-flung network, which monitors the air breathed by about 90 percent of the U.S. population, is one of the nation’s first defenses against a terrorist attack. Air samples obtained from the monitors are frequently subjected to a quick, polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based DNA test designed to detect a handful of dangerous bacteria, such as those that cause anthrax and botulism.

Samples that don’t contain dangerous pathogens based on the PCR test are then sent to Berkeley Lab, where they’re exposed to a vastly more comprehensive test capable of detecting 10,000 types of organisms. The test employs a glass chip manufactured by a company called Affymetrix using specifications provided by Berkeley Lab scientists. It boasts a carpet of DNA, with each of the 500,000 carpet strands sporting a section of DNA identical to a section of DNA in one of the 10,000 types of bacteria.

|

|

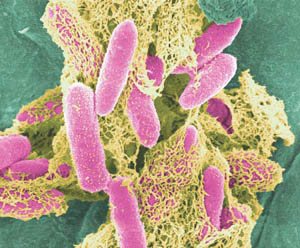

| E. Coli bacteria | |

When an air sample arrives at the lab, its bacterial DNA is separated, fluorescently labeled, and washed over the carpet. If DNA from the air sample finds its counterpart on a carpet strand, it attaches itself to the strand, indicating a match. The more matches of DNA specific to a type of bacterium, the more likely that bacterium is in the sample.

“We rely on the statistical significance of many tests coming up positive,” says DeSantis. “The trick was choosing the 500,000 pieces of DNA that will test for all 10,000 types of bacteria.”

The Berkeley Lab team can churn through 30 air samples in a single week, with each sample representing a week’s worth of collected bacteria. They’ve analyzed hundreds of samples since they started the nationwide background census one year ago, and hope to eventually analyze thousands, enough to cover the entire nation for one year. So far, each sample has yielded hundreds of different organisms from several branches of the taxonomic tree. Many of the bacteria are hardy spores, able to transform from food-gathering organisms in the presence of water to a tight ball of DNA protected by a hard protein coating when water disappears.

“And in many cases we are finding very close relatives of anthrax,” says DeSantis. “It emphasizes the importance of designing anthrax tests sensitive enough to differentiate between harmless and harmful types of Bacillus, to avoid false positives.”

They’re also finding E. Coli and other organisms that usually reside in animal intestines. Interestingly, these bacteria are more prevalent in urban areas than rural areas, perhaps because there’s more sewage and garbage.

The team will soon publish a pilot study that chronicles the ebb and flow of airborne bacteria in San Antonio and Austin over a 20-week span. Feedback from the study will help them determine how to best present the volumes of data they’re producing — an important refinement given that a one-week air sample contains about 100 megabytes of data.

They also hope to give scientists interested in the distribution of airborne bacteria access to their research on the web. For example, a field researcher investigating why birds near a lake are contracting a disease can mine the data to determine which bacteria inhabit upwind regions.

“This is the largest census to date of airborne microbial matter,” says DeSantis. “There are other ways to do this, such as cloning and sequencing, but they are more expensive and time-consuming.”

Horst Simon Named Associate Lab Director for Computing Sciences

BY JON BASHOR

|

|

| Horst Simon |

Horst D. Simon, an internationally recognized expert in high performance computing, has been named associate laboratory director for computing sciences at Berkeley Lab.

“I’m extremely pleased to have Horst assume this responsibility,” said Director Charles Shank in announcing the appointment. “This is a critical time for the Laboratory’s computing sciences programs, and I greatly value Dr. Simon’s leadership. I look forward to working closely with him in these important assignments.”

Simon joined Berkeley Lab in early 1996 as director of the newly formed National Energy Research Scientific Computing (NERSC) Division, and was one of the key architects in establishing NERSC at its new location in Berkeley. The NERSC Center, founded in 1974, is DOE’s flagship facility for unclassified supercomputing. Simon is also the founding director of Berkeley Lab’s Computational Research Division, which conducts applied research and development in computer science, computational science, and applied mathematics.

As associate laboratory director for Computing Sciences, Simon will have overall responsibility for three LBNL divisions: the NERSC Center, Computational Research, and Infor-mation Technologies and Services. He will continue to serve as division director for both NERSC and Computational Research.

At the Feb. 23 all-hands meeting where the appointment was announ-ced, Simon thanked Director Shank for his “vision and leadership” in working to expand the contributions of computational science to Berkeley Lab research projects. He also thanked the former associate Lab director Bill McCurdy for his mentorship in the ways of DOE and the national labs.

|

|

| Horst Simon leads visiting Swiss scientists on a tour of NERSC. | |

Noting that his already-crunched schedule was likely to become even more crowded, Simon encouraged employees to seek him out whenever they had ideas or issues to discuss. “I really look at this position as being one where you don’t work for me, but one in which I work for you,” he said.

In making the announcement, Director Shank noted that Simon “is widely respected for his contributions to science.”

Simon earned his Ph.D. in mathematics at UC Berkeley and continues his research in the development and application of high performance linear algebra algorithms. His recursive spectral bisection algorithm is regarded as a breakthrough in parallel algorithms for unstructured computations. His algorithm research efforts were honored with the 1988 Gordon Bell Prize for parallel processing research.

Simon is also widely known for his work in assessing the performance of supercomputers. He was member of the NASA team that developed the NAS Parallel Bench-marks, a widely used standard for evaluating the performance of massively parallel systems. He is also one of four editors of the twice-yearly “TOP500” list of the world’s most powerful computing systems.

From 1994 to 1996 Simon worked for the advanced systems division of Silicon Graphics, Inc. From 1989 to 1994, he worked for Computer Sciences Corporation as manager of a research department supporting the NAS (Numerical Aerodynamic Simulation) systems division at NASA Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif. Before that Simon was the manager of the computational mathematics group of Boeing Computer Services, where he worked from 1983-1989.

High Schoolers Dazzle in Science Bowl as Lab Volunteers Cheer

Them On

BY RON KOLB

|

|

| Harker School student Lev Pisarsky requests an explanation from the judges as his teammates (from left) Anjali Vaidya, captain Mason Liang, and Yi Sun listen intently. |

As Harker High School was rumbling through the field of 16 other schools toward victory in the Regional Science Bowl competition, held at Berkeley Lab last Saturday, it developed an interesting way of warming up and getting juiced for the next match: the boys played poker.

“We are not talking about nervous kids here,” said their proud coach, Robbie Korin. “They wanted to win, but I’m not sure they had any expectations.”

Guided through the day by Berkeley Lab materials scientist Doug Owen, science education coordinator Rollie Otto, and regional Science Bowl Director Ray Ng of Sandia National Lab, the nearly one hundred competing students, coaches and families bounced from conference room to conference room, taking on randomly selected opponents. From the morning’s round-robin to the afternoon’s double-elimination finale, young men and women matched speed and intelligence in a college-bowl-like battle of wits.

Each match featured two eight-minute halves, during which a moderator fired question after question at the four-student teams in areas like astronomy, biology, chemistry, math, earth and computer sciences. A correct four-point toss-up question could lead to a 10-point bonus question.

|

|

| Berkeley Lab’s Doug Owen (at left) and the Science Bowl judges offer a bonus question to the runner-up Albany High School team. | |

When the answer buzzers were silenced, only two teams were left standing:

Albany High, a multiple winner of regional contests and the 1993 national

champion, and Harker, which has only been a high school for six years

(previously a private pre-secondary school founded in 1893). Harker

had been eliminated in the first round of the regionals last year.

The two clashed earlier in the day during preliminary rounds, and Harker won rather easily. Then, facing elimination in the afternoon, Albany came back to beat Harker, 88-44. Was Harker worried? You couldn’t tell by their poker faces.

“These students are fearless,” coach Korin said. “They’re not afraid to be wrong. And that’s the key — it’s a very bright, confident group who are willing to push the buzzer. Some kids are book-smart, but they hesitate to hit the buzzer.”

|

|

| Volunteer Valarie M. Espinoza-Ross of ASD keeps score during one of the rounds. |

Not so Lev Pisarsky, Jasper Shau, Yi Sun, Anjali Vaidya and Mason Liang. They came out blazing, took an early lead and then coasted to the championship by beating Albany in the deciding match, 136-72. That earned them an all-expenses-paid trip to Washington D.C. for the Department of Energy’s 14th annual national championship, to be held from April 29 to May 3. There, they’ll face 65 other champions.

Korin has coached all 14 years at different schools and he’s never made the trip to the nationals. This group, he said, is special, an extremely bright quintet from a 550-student academic private school in San Jose who worked hard for what they earned. They would practice every Friday for 30 minutes during eighth period, and they regularly appeared on “Quiz Kids,” a Peninsula-based TV game show with rules not unlike the Science Bowl (it’s on KRON-TV Saturdays at noon).

DOE Berkeley Site Office Manager Dick Nolan called Berkeley Lab “a very impressive and inspirational setting for this year’s regional competition,” the program having returned to the Hill after many years of absence. Laboratory volunteers who kept the clocks and the scoreboards made things run smoothly.

And for Harker, it was as easy as a rousing game of five-card stud.

|

|

| Deputy Director Sally Benson bestows a medal upon Harker’s Mason Liang as fellow champions Yi Sun and Anjali Vaidya await their turns. | |

|

|

|

| Robbie Korin, the coach of the winning Harker High team. | ||

Science Bowl questions: How Would You Do?

Below are sample questions from the Science Bowl competition. How

many can you answer correctly? (Answers below)

1. What is a general term for a very fine textured, fissile, sedimentary

rock composed of clay, mud and silt?

(W) Slate

(X) Schist

(Y) Arkose

(Z) Shale

2. The chemical difference between chlorophyll a and b is that a methyl group in chlorophyll b is replaced by what group in chlorophyll a?

3. When does equilibrium, such as liquid-solid or liquid-gaseous, exist between two phases?

(W) The rate of reaction is not affected by raising or lowering either

the temperature or the pressure

(X) The rate of reaction between the two phases becomes zero

(Y) The individual molecules in each phase remain stationary

(Z) An equal number of atoms or molecules is continually interchanged

between the phases

4. The Saros cycle refers to:

(W) The 11-year solar sunspot cycle

(X) An 18.6-year cycle of eclipses

(Y) The 25,800-year cycle of the precession of the Earth’s axis

(Z) The 29.5-day synodic lunar month

5. What kind of speciation is the appearance of a new species within

a single population?

6. What is the length of the body diagonal of a cube with each edge

equal to 1?

(W) Square root of 2

(X) Square root of 3

(Y) 1

(Z) 2

7. What is the name of an add-on board that creates digital music?

8. To decrease the centripetal force on an object traveling in a

circular path, you can:

(W) Increase the speed of the object

(X) Increase the mass of the object

(Y) Increase the radius of the circle

(Z) Decrease the radius of the circle

Berkeley Lab Volunteers in Science Bowl

Jim Morel, Nuclear Science

Jorge Hernandez, Directorate

George Chao, Engineering

Loida Bartolome-Mingao, Human Resources

Valerie Espinoza, Administrative Services

Liz Moxon, Advanced Light Source

Ron Kolb, Directorate

Reid Edwards, Directorate

Sally Lafferty, Information and Technical Services

Margetta Campbell, Information and Technical Services

Elizabeth Bautista, NERSC

John Hutchings, Facilities

Rollie Otto, Directorate

Julia Chamberlain, CSEE

Molly Stoufer, Administrative Services

Susan Aberg, Directorate

Eric Feng, Directorate

Adewunmi Adeyemo, Directorate

Roy Kerth, Physics

David Baca, Accelerator and Fusion Research

Doug Owen, Materials Sciences

Tommy Wilkinson, ALS

Dominic Passanisi, Directorate

Director Distributes Royalty Checks to Inventors

|

|

| Left to right are, in the front row: Ender Erdem, Duo Wang, Paul Luke, Robert Nordmeyer, William Kolbe, Stephen Holland, and Albert Ghiorso; second row: Fred Winkelmann, Nicholas Sauter, Fred Buhl, Dr. Shank, Chin-Fu Tsang, Tony Hansen, Delia Milliron, Robert Cheng, Stephen Selkowitz, Paul Adams, and Nigel Moriarty. Photo by Roy Kaltschmidt, TEID |

In Fiscal Year 2003, technology licensing agreements yielded $1.5 million for 112 scientists whose inventions Berkeley Lab transferred to industry, including $547,000 in cash payments and $954,000 worth of publicly traded stock. Not including the stock, the average distribution was $4,819, with the highest check totaling about $45,000. Cash distributions to inventors have grown every year and have doubled over the last three years. Approximately $1.4 million in additional licensing income from FY 2003 will go to the Lab, to be used primarily for research and development.

Get Involved: Join or Start a New Club

|

|

| Employees stretch out with the Yoga Club. | |

If the existing groups don’t fit your needs, employees are welcome to create a new club. It’s easy to do. First, interest in a particular area should be gauged to make sure enough members will join. Then visit the EAA website, which can be found in the A-Z index on the Lab home page. Located there are the forms and information you need to get a group started.

Each year, the Lab provides about $25,000 for funding Lab clubs, says Angela Dawn, the current coordinator for EAA.

“Support for activities are evaluated based on their proximity to the Lab, their relation to the workday, the level of Lab community spirit created, the cost per employee, and the number of employees served,” she explains.

In addition to funding, all Lab clubs are given access to several Lab resources, including the use of meeting rooms, e-mail, phones, copy machines, paper, and bulletin boards.

“Our only requirements, really, are that a group provide some type of wellness, recreation, cultural, or educational benefit to employees of the Lab,” says Dawn. “And every club must be open to all employees and their families.”

Volunteers are also needed for the EAA panel. Elections to four-year

terms are held annually. Questions about volunteering, signing up

for clubs, and creating new ones should be sent to [email protected].

-- Lyn Hunter

Registered Employee Activities Association Clubs

Contact information for each group is available at the EAA website.

Arts Council

Bike Coalition

Breast Cancer Research Awareness Forum

Chinese and Asian Association

Dance Club

Gay, Lesbian & Bisexual Association

Golf Club

Green Team

Latino and Native American Association

Macintosh Users Group (MUG)

Martial Arts Club

Music Club

Outdoor Archery Club

Postdoctoral Society

Soccer Club

Softball League

Table Tennis

Tennis Club

Ultimate Frisbee Club

Volleyball

Yoga

Berkeley Lab View

Published every two weeks by the Communications Department for the

employees and retirees of Berkeley Lab.

Reid Edwards, Public Affairs Department head

Ron Kolb, Communications Department head

EDITOR

Monica Friedlander, 495-2248,

[email protected]

Asscociate editor

Lyn Hunter, 486-4698,

[email protected]

STAFF WRITERS

Dan Krotz, 486-4019

Paul Preuss, 486-6249

Lynn Yarris, 486-5375

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Jon Bashor, 486-5849

Allan Chen, 486-4210

FLEA MARKET

486-5771, [email protected]

Design & Illustration

Caitlin Youngquist, 486-4020

TEID Creative Services

Berkeley Lab

Communications Department

MS 65, One Cyclotron Road, Berkeley CA 94720

(510) 486-5771

Fax: (510) 486-6641

Berkeley Lab is managed by the University of California for the U.S.

Department of Energy.

Online Version

The full text and photographs of each edition of The View, as well

as the Currents archive going back to 1994, are published online on

the Berkeley Lab website under “Publications” in the A-Z

Index. The site allows users to do searches of past articles.

‘Gersonfest’ Celebrates a Remarkable Life in Physics

BY PAUL PREUSS

|

|

| Gerson Goldhaber with his son Nat. |

On Saturday, Feb. 21, more than 150 fans of Gerson Goldhaber, including numerous renowned physicists and their spouses and children — many of whom are also physicists — gathered at Berkeley Lab for a “Gersonfest” celebrating his 80th birthday and the 50th anniversary of his arrival at the Lab.

Indeed, lots of the physicists and physicist-children present were also named Goldhaber. Several of them gave presentations during the day-long symposium in Perseverance Hall, including Gerson’s older brother Maurice, a former director of Brookhaven National Laboratory, Maurice’s son Fred — who protested “It’s not true we outnumber everybody else” — and Fred’s son David Goldhaber-Gordon. David concluded his talk on nanoscale electronic devices by noting the long legacy: “I’m in the seventh generation of Goldhaber physicists,” he said, but instead of taking up particle physics, “I staged a rebellion by going into condensed matter.”

The symposium’s sessions seemed inspired by what the Lab’s Willi Chinowsky, one of the organizers, called the “phase changes of Gerson’s career.” Goldhaber phases roughly correspond to experimental techniques favored by him at different periods. He devised the first of these, photographic emulsions loaded with heavy water for recording particle interactions, in the 1940s while still a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin.

In the 1950s he used emulsions to study meson-nucleon interactions, first at Columbia University and then at Berkeley Lab. For 20 years Gerson employed emulsions and the Bevatron’s bubble chamber to productive effect in researching antinucleons, “strange” kaons, other mesons and many subatomic phenomena.

Gerson’s next phase change came in the early 1970s, when he and George Trilling led a Berkeley Lab team in collaboration with physicists at the Stanford Positron Electron Asymmetric Ring, SPEAR — a machine so temperamental, said Chinowsky, that it was often referred to as SHAFT. In 1974, in the famous “November Revolution,” the group discovered the psi meson (subsequently called the J/psi).

Later Gerson and his colleagues proved what until then had only been assumed, that the psi consisted of a new quark, the charm, and its antiparticle, combined as “charmonium.” Gerson became so well known for establishing the existence of charm, his brother Maurice noted later that evening, that once when he followed Gerson at a conference Maurice introduced himself as “the Goldhaber without charm.”

In his own presentation at Gersonfest, Trilling wryly described Gerson’s

most dramatic phase change: “In the late 1980s Gerson decided

to join the Supernova Cosmology Project, while I went into the Superconducting

Super Collider. You can draw your own conclusions.” (The ill-fated

SSC was cancelled by Congress in 1993.)

|

|

| Gosta Ekspong from Sweden, Gerson Goldhaber, Don Glaser, and Per Carlson from Sweden engage in lively conversation. | |

Saul Perlmutter recalled that the fledgling Supernova Cosmology Project (SCP) had only a “graduate student and a programmer” until cofounder Carl Pennypacker got Gerson involved. He proved to be the “first of a new wave of particle physicists committed to astrophysics.” Eventually Gerson helped write software for automating the pioneering SCP technique of discovering supernovae among the new bright spots in identical images of thousands of distant galaxies, taken weeks apart.

At first, however, Perlmutter said, “Gerson preferred doing it by eye,” and he was a whiz at it. Most of the bright spots turned out not to be supernovae (“For months Gerson was showing up with great plots of asteroids”) but once he and his teammates became adept at eliminating the background, discovery moved into high gear.

“Gerson brought us the collegiality of the particle physics world, essential to our group effort,” Perlmutter said. This included hosting parties where a bottle of champagne was opened for each new supernova, although “by the time we got up to 42 supernovae, the champagne bottles had to be symbolic.” In 1998 the SCP announced the accelerating expansion of the universe, among the most important scientific discoveries of the century.

A gala dinner Saturday evening celebrated milestones in a life of

adventure that began in Chemnitz, Germany, on Feb 20, 1924, moved

to Cairo, Egypt to escape the Nazis, then on to Jerusalem during World

War II. There, at Hebrew University, Gerson met his first wife, chemist

and physicist Sulamith Löw, who worked with him until her death

in 1965. He married Berkeley Lab science writer Judith Margoshes Golwyn

in 1969; children of both marriages were among the numerous Goldhabers

present at the celebration.

Gersonfest was organized by Willi Chinowsky, Bob Cahn, Tony Spadafora,

and Jeanne Miller. More information, including Gerson’s biography,

historical photos, and lists of symposium topics and participants,

can be found on the web at http://inpa.lbl.gov/scp/Gersonfest/goldhaberSymposium_main.htm.

Testing a Better Car Battery for electric vehicles

BY ALLAN CHEN

|

|

| Electric vehicles such as this two-seater GEM (Global Electric Motorcars) may be very endearing, but cannot reach performance levels similar to those of regular cars. Scientists at Berkeley Lab are testing battery materials in the hope of developing a better performing battery for electric and hybrid-electric vehicles. |

Building a better battery is a key goal for those who would like to see electric and hybrid-electric vehicles become viable options in the car market. Progress has been slow, however, as researchers seek to improve battery materials so they can last longer, suffer less degradation, and operate safely over wider temperature ranges than is currently possible.

A unique cell development program under way at Berkeley Lab is making an important contribution to this effort. Scientists in the Environ-mental Energy Technologies Division (EETD), led by Kathryn Striebel, use standardized cells to assess the performance of promising new materials in a working battery. The project aims to bridge the gap between materials research and commercial battery development. Funded by DOE’s Batteries for Advanced Transportation Technologies program, the project involves Berkeley Lab and other institutions and national laboratories.

“The idea is to take new materials from labs and build them into test cells for new batteries,” says Striebel. “We build new materials from different sources into these test cells and run a set of standard tests to see how they perform under realistic conditions.“

Experimental materials come from labs all over the world, including EETD’s own electrochemistry labs. The testing helps determine why electrode materials fail or degrade. To be successful, a battery for automotive applications must meet DOE criteria for features, such as weight, cost, power density, and operating temperature range.

“The central goal for us,” Striebel says, “is to determine which materials work the best — and when they fail, to answer the question ‘why?’”

Currently, lithium-ion-based cells show promise for meeting these performance goals. A candidate for the chemistry of lithium-ion batteries is lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4). The material has many advantages, but the capacity of LiFePO4 batteries is currently insufficient for use in vehicles.

In fact, no material meets all of DOE’s goals for automotive batteries. A key reason is that the performance of existing materials drops significantly after many charge-discharge cycles. “If we can nail down the mechanisms of degradation, it will be a great help to everyone working in the field,” Striebel says.

The program’s test cells are small, thin pouches (12 square centimeters in area and about 3.5 centimeters on a side) that can store an average of 12 milliampere-hours of charge.

|

|

| A few grams of experimental battery material are mixed with carbon and cast on a foil current collector (left) to make test-cell pouches 3.5 centimeters on a side (center). Up to 64 cells are tested simultaneously (right), under conditions like those in a hybrid-electric vehicle battery. | |

The effort to make a cell starts with 5 to 20 grams of an experimental material which is mixed with carbon and cast in thin layers onto a foil current collector. One anode and one cathode are placed in a specially designed pouch and transferred to a helium-filled glove box for finishing. After being sealed, the pouch is compressed and mounted on a test stand.

The tester can charge and discharge up to 64 test cells simultaneously, according to any specification, including simulating the conditions of a hybrid-electric vehicle battery. It measures current, voltage, and other parameters, and for each test cell provides impedance characteristics, capacity, and power as a function of time or number of cycles.

Once the cell is disassembled, Striebel and her colleagues may subject the experimental material to a range of additional tests to investigate its degradation mechanisms. These tests might use Raman spectroscopy, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, and other spectroscopic methods; X-ray diffraction; and transmission electron microscopy.

"The testing is an ongoing program," says Striebel. "We continue to test new materials as they are developed. The results allow us to compare the performance of different materials with one another." Striebel's group has also been working with that of John Newman of EETD and UC Berkeley, developing computer models of battery performance.

Test results are presented at U.S. and international meetings and published in peer-reviewed journals, so the data are available to the scientific community as well as to battery developers.

Virtual Flames Yield Fiery Insights

|

|

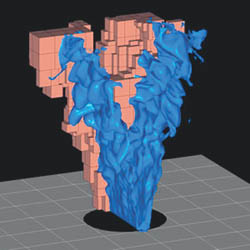

| This simulation was based on 20 chemical species and 84 fundamental reactions. The computed surface exhibits large-scale wrinkling of the instantaneous flame surface, and when averaged over time, shows remarkable agreement with photos in terms of flame brush thickness, spreading and growth rates. |

To learn more about basic combustion processes, Berkeley Lab researchers have created the first detailed computer simulations of laboratory-scale turbulent flames. Their models, which use 3-D software to portray the chemical fidelity and fluid transport of flames at an unprecedented level of detail, have applications for improving power generators, heating systems, water heaters, stove, ovens, and even clothes driers.

Marc Day and John Bell of the Computational Research Division’s Center for Computational Sciences and Engineering (CCSE) are simulating several turbulent premixed flame experiments underway at the Combustion Laboratories in the Environmental Energy Technologies Division (EETD). Working with Robert Cheng and Ian Shepherd of EETD, the CCSE researchers carried out impressive validations of their unique simulation code using software that does not utilize phenomenological models for under-resolved physical phenomena.

While most simulations of this type use such models, CCSE’s capabilities exploit adaptive gridding methods, mathematical filtering, and very large scale parallel computing hardware in order to conduct laboratory-scale simulations at a level much closer to a direct numerical simulation. Beyond the initial validation work, the computations offer a glimpse into the inner workings of the combustion process previously hidden from experimental measurement.

The investigations are focused on two areas: how turbulence in the fuel stream affects the local combustion chemistry, and how emissions are formed and released in the product stream. Simulation at such a level of detail was impossible a few years ago. However, over the past five years, algorithmic improvements by applied mathematics groups such as CCSE have slashed computational costs for these types of studies by a factor of 10,000. These savings enable improvements in the fidelity of the chemical and fluid descriptions of the flows, to the point that experiments may now be simulated without ad hoc engineering models for under-resolved physical processes. Nevertheless, simulation of practical-scale combustion devices remains an immense undertaking.

By implementing its advanced simulation algorithms on state-of-the-art parallel computing hardware, CCSE has increased the number of variables available for describing the system from hundreds of thousands five years ago to more than a billion today.

The solutions computed by CCSE are being validated with experimental data provided by EETD’s Combustion Lab. The researchers are also probing massive amounts of data generated by the computations in order to learn more about flame details, such as the effects of eddies on the structure of the combustion reaction zone. CCSE is also working with EETD researchers to develop additional statistical measures of both the simulation and experimental data, so that they can obtain more detailed quantitative comparisons. Beyond experimental validation, the solutions will be used to track the fate of fuel particles as they wash through the flame and undergo a range of chemical reactions that contribute to pollutants or unburned hydrocarbon emissions.

Flea Market

- AUTOS & SUPPLIES

‘99 FORD WINDSTAR LX MINIVAN, V6 3.8L, 73K mi, runs great, clean cabin, no smoking & pets, fully equipped, cruise, ABS, dual air bags, alloy wheels, Karr sec syst, rear ac, privacy glass $7,900, Keiji, X5850, 525-3790

‘95 TOYOTA,CAMRY, LE sedan, 4 dr, auto, 64K mi, JBC CD player w/ 12 CD changer, sliding sunrf, $7,300, 205-4883

‘95 OLDS CUTLASS CIERRA, white w/ blue inter, V6 3.1 L, 154K mi, ac, auto, pwr steer, ABS, $2,000/bo, Laura, X5351, (650) 728-3878

‘89 FORD PROBE GL, 116K mi, 2 dr hatchback, 5 sp stick, pwr steer, runs well, Owen, X5462

‘88 DODGE RAM CHARGER, blue two tone w/ blue inter, V8 360 138K mi, ac, pwr steer/breaks $2,000/bo, Laura, X5351, (650) 728-3878

‘86 HONDA CRX, new tires, needs a valve job, regist as non-operational, $900/bo, Steve, X2525, (209) 832-5042

HOUSING

ALBANY, 2 bdrm/1 bth house, freshly painted, fp, fenced yard w/ fruit trees, lge storage shed, gardener, lge kitchen w/ dw, refrig, gas stove, w&d, nr Solano Ave & El Cerrito Pl, avail now, no smokers/pets, $1,750 mo, 1st mo + $1,000 sec dep, 526-4007, Ilan

BERKELEY HILLS, furn suite by the wk/mo for visitors to UCB/LBNL, modern, priv home, elegant, spacious & comfortable, beautiful bay views, can walk down to UCB, [email protected], 848-1830

BERKELEY, studio inlaw apt, sep entr, quiet, nr shops/rest/BART/trans, nr campus, incl w&d, water, garbage, 12-mo lease, no pets/smoking, $525/mo + util, avail 3/1, Vlad or Linda, 849-1579, [email protected]

CENTRAL BERKELEY, nice furn rms, kitchen, laundry, PC, DSL, hardwd flrs, brkfst, walk to campus/shops, $800/mo, incl everything, 845-5959, [email protected], Paul, X7363

DOWNTOWN BERKELEY fully furn sunny lge studio, sep kitchen w/ lge table/desk, perfect for visiting postdoc, avail 3/1, (800) 455-3863

NORTH BERKELEY HILLS, beautiful, warm & spacious 3 bdrm/2.5 bth unfurn home, 1yr lease, liv rm w/ fp, din rm, bi-level deck, creek, lovely garden, lge eat-in kitchen, hardwd flrs, leaded glass windows, 1938 charm, refrig, gas stove, w&d, DSL, 2-car garage, storage, $2,500/mo + $3,500 sec dep, incl gardener, garbage, home warr, no pets/smokers, avail 3/13, Terry, 910-0086, [email protected]

NORTH BERKELEY HILLS, furn 2 bdrm/2bth house sublet, avail immed for 2.5 to 4 mos, nr LBNL, serene leafy setting, fenced yard, hardwd flrs, pets welcome, $1,780/mo, Susan, 841-4889

NORTH BERKELEY HILLS, short-term accomm in beautiful home nr Kensington/ Tilden Park, nr #7 bus, Asia suite has queen bed, persian rug, desk, priv bth & phone line, $95/night, 3 night min, or $600/ wk incl kitchen & laundry, no pets/smokers, Terry, 528-9970, [email protected], www.geocities. com/hillshomestay/photos.

NORTH BERKELEY lge & sunny fully furn 1/1 Victorian flat, laundry, gated carport, walk to Lab shuttle/UCB, by wk/mo/ semester, avail 4/15, gfchew@mindspring. com, 848-1830

NORTH BERKELEY, B&B close to Lab shuttle, lge furn rm w/TV & phone, linens & sheets provided, brkfst, Dominique, avail immed, $850/mo, 527-3252

OAKLAND/Upper Rockridge house, 3 bdrm/ 1 bth, stove & refrig, hardwd flrs + carpets, very clean, fenced-in yard/patio, storage in bsmt, sep gar + parking, great location, nr Lake Temescal, lease, $1,700/mo +dep, Al, 925-377-1096

ROCKRIDGE, rm in spacious 6 bdrm house, approx 12’x13’ w/ 3’x12’ walk-in closet, 2-story house, 2 bths, lge liv area & kitchen, gas stove, dw, w&d, storage, good light, quiet, easy parking, share w/ 5 professionals & grad students, $555/mo + 1/6th shared util, approx $50/mo, dep $800, move-in flex (April 3-15), nr UC/BART/shops, no smoking/pets, X4744, Judy, [email protected]

MISC ITEMS FOR SALE

CONTEMPORARY LEATHER SOFA, 7 mo old, $300/bo; stereo syst w/ state-of-the-art speakers, no remotes, $200/bo; coffee table, charcoal color, not great coffee table but makes great tv/stereo table $25, Paijoun, [email protected]

MOVING SALE, all items in exc cond: Bose 301 speakers, $75 for pair, coffee table, $50, stereo cabinet, $20, lamps, $10/ea; end table, $10, John, X7457, 635-0652

NIKON CAMERA, 35mm, 35-70mm zoom w/ red eye reduc & self timer, good cond, $65/bo; twin size bed w/ matt, box frame, bed skirt, good cond, $95/bo; full size futon w/ blk metal frame, good cond, $120/bo; med size microwave, good cond, $35/bo; porcelain dinnerware (4 sm/4 med/1 lge plate), $10; misc dinner plates, mugs, container, chopsticks, Minmin, 847-5130

PANASONIC TV 25” color CTG-2530, video & audio jacks, quartz tuning, modern wood cabinet, exc pict, exc cond, $65; TV swivel base 24”x15” $10, Ron, X4410, 276-8079

SOLID OAK KITCHEN CABINETS, used, exc cond, incl double oven & trash comp, $1,250/bo, Steve, X2525, (209)832-5042

LOST AND FOUND

FOUND: bracelet in the 50A-2124A women's bathroom, silver link bracelet w/ amber, Melissa, X6776

FREE

CAT, shorthair female, spayed, mostly white, indoors only, had front claws removed by previous owner, shots up to date, X4039

FIREWOOD, John, X7457, 635-0652.

WANTED

DOG BOARDING in your home, going on vacation for 2 wks, beg 3/21, need to leave my very-well-behaved springer spaniel in good hands, fee neg, 601-5757

USED CAR, Toyota or Honda, less than 10 years old, Joe, X7284

VACATION

LAKE TAHOE house, 3 bdrm/2.5 bth, fenced yard, quiet sunny location, skiing nearby, great views of water & mountains, $195/night, 2 night min, Bob, (925) 945-9345

PARIS, France nr Eiffel Tower, fully furn sunny & comfortable 2/1 flat in modern bldg, close to everything, perfect for vacation/sabbatical, by wk/mo, [email protected], 848-1830

Flea Market Policy

Ads are accepted only from Berkeley Lab employees, retirees, and onsite DOE personnel. Only items of your own personal property may be offered for sale.

Submissions must include name, affiliation, extension, and home phone. Ads must be submitted in writing (e-mail: fleamarket@ lbl.gov, fax: X6641,) or mailed/delivered to Bldg. 65.

Ads run one issue only unless resubmitted, and are repeated only as space permits. The submission deadline for the Mar. 19 issue is Friday, Mar. 12.

LDRD Call for Proposals for FY05

Director Charles Shank has issued the FY 2005 Call for Proposals for the Laboratory Directed Research and Development (LDRD) program, which provides support for projects in forefront areas of science that can enrich Berkeley Lab’s R&D capabilities and achievements.

Multi-investigator and multidivisional initiatives that address problems of scale are especially encouraged. All projects should have a clearly stated problem (e.g., DOE mission or addressing a national need), coherent objectives, and a well-considered plan for leadership, organization and budget.

The Call for Proposals has been distributed to division directors and business managers. Principal investigators must submit proposals to division directors by April 16.

After an internal divisional review and evaluation, division directors will forward the proposals to the director’s office. They will then present the proposals from their respective divisions to review committees comprised of the director, deputy directors, associate laboratory director, and other division directors. The director will make the final decisions.

The complete call, schedule, guidance, and forms are available for downloading on the Lab home page under the heading “Publications” and then “LDRD,” or directly at http://www.lbl.gov/Publications/LDRD/.