Berkeley Lab Collects Three R&D 100 Awards

The Elements of a Lifetime

Berkeley Lab Collects Three R&D 100 Awards

For the first time since 1992 Berkeley Lab has captured three R&D Magazine R&D 100 awards in a single year. The new awards — for the Neural Matrix CCD, the Optical Sound Restoration System, and Ion Mobility Analysis — bring the Lab’s total haul of these “Oscars of Invention,” first awarded in 1963, to 37.

“Two of this year’s winning technologies have already been licensed by the Technology Transfer Department to companies that are working to bring them to market and benefit the public,” says Tech Transfer’s Pam Seidenman, “and the third may be deployed by the Library of Congress.”

A virtual co-winner of the year’s awards, Tech Transfer led teams of writers who helped the scientists craft the complex and demanding nominations and explain their work in terms that brought home its value to nonspecialist judges.

The Neural Matrix CCD, a novel technology for patterning and monitoring networks of growing neurons, was created by Ellie Blakely, Kathy Bjornstad, and Chris Rosen of the Life Sciences Division, Ian Brown and Othon Monteiro of the Accelerator and Fusion Research Division, and Jim Galvin of Engineering, with Blakely and Brown leading the team and Jim Miller of the Creative Services Office (CSO) writing the nomination. Cellular Bioengineering, Inc., Honolulu, Hawaii, participated in the research and shares the R&D 100 Award.

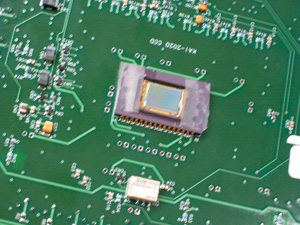

The Neural Matrix CCD monitors living neurons on an electric chip.

The Neural Matrix CCD is the first technique for crafting large arrays of networked neurons on a charge-coupled device. Diamond-like carbon deposited on the optical surface of the CCD is patterned in fine detail, then coated by a continuous layer of cell-culture collagen, which is seeded with living neurons. The CCDs record changes in electrical potential from each of these millions of individual nerve-cell sensors in real time, precisely mapping each neuron’s activity within the neural network.

Initially designed to help scientists learn how neurons in the human nervous system communicate with each other, the Neural Matrix CCD is the first step toward bio-electronic chips that can restore the use of limbs and eyesight and improve mental function in patients, or provide neural networks of living cells for testing drugs and sensing neurotoxins.

The Optical Sound Restoration System, the first “touchless” technology for restoring audio recordings on metal foil, wax, plastic, and other media regardless of scratches, warping, or mold, was created by Carl Haber and Vitaliy Fadeyev of the Physics Division. Julie McCullough, formerly of CSO, and Pam Seidenman wrote the nomination, and Loretta Hintz, also formerly of CSO, produced a video that brought the technology to life.

The Optical Sound Restoration System reconstructs the original sound from a wide range of media, from cylinder and wax recordings to plastic LPs, bringing back to life voices of the past.

The Optical Sound Restoration System reconstructs the original sound from a wide range of media, from cylinder and wax recordings to plastic LPs, bringing back to life voices of the past.

Since 1877, when Thomas Edison recorded “Mary had a Little Lamb” on a tinfoil cylinder, recordings on such diverse media as shellac discs, acetate sheets, and plastic dictation belts have captured an incredible range of material: the arias of Enrico Caruso; the poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay; the lost language of Ishi, the last Yahi Indian; the words of historical figures like Alfred Lord Tennyson and Amelia Earhart. Many can no longer be played and are too delicate for traditional restoration.

By adapting methods for analyzing particle tracks in high-energy experiments, Carl Haber and Victor Fadeyev developed a method for restoring these damaged and fragile recordings. Without ever touching the cylinder, disk, or belt, they create two- or three-dimensional digital images of the surface that can be computer-analyzed to reconstruct the recorded sound in high fidelity.

Archivists estimate that 40 percent of the millions of recordings in the world’s major sound archives could benefit from restoration with the Berkeley Lab technology.

Ion Mobility Analysis, the first technology for fast, inexpensive, accurate measurement and counting of individual lipoprotein particles, was developed by Ron Krauss of the Life Sciences Division, now of Genomics, with Henry Benner, formerly of Engineering, and Patricia Blanche, presently a guest in the Genomics Division. Bruce Balfour of CSO wrote the nomination.

Ion Mobility Analysis makes use of a differential mobility analyzer and particle counter (left), an electrospray unit (center), and a computer to sort and count the numerous classes and subclasses of lipoprotein particles.

Ion Mobility Analysis makes use of a differential mobility analyzer and particle counter (left), an electrospray unit (center), and a computer to sort and count the numerous classes and subclasses of lipoprotein particles.

For over fifty years, standard tests that measure levels of total cholesterol, “bad” low-density lipoproteins, “good” high-density lipoproteins, and triglycerides have been used to evaluate the risk of heart disease. But half the heart attacks in the U.S. each year strike people with normal cholesterol levels. The distribution of size, quantity, and type of lipoprotein particles — which are much more various than standard tests can account for — provides a far better indicator of whether or not someone is at risk.

Benner, Krauss and Blanche developed ion mobility analysis to measure the size distribution and count the individual particles in all classes of lipoproteins in a single analytical step. The technology measures the drift of charged, aero-solized lipoproteins as they are drag-ged through air by the force of an electric field. Charge and drift velo-city separate the particles by weight and size, and the sorted particles travel to a detector for counting.

The winners of this year’s R&D awards will receive plaques at R&D Magazine’s formal awards banquet, to be held at Chicago’s Navy Pier on October 20.

The Elements of a Lifetime

A Scientific Celebration of Al Ghiorso�s 90th Birthday

AFRD's Rick Gough presents Al Ghiorso with a sign announceing the designation "Ghiorso Plaza," an area adjacent to Seaborg Glen behind Building 71.

AFRD's Rick Gough presents Al Ghiorso with a sign announceing the designation "Ghiorso Plaza," an area adjacent to Seaborg Glen behind Building 71.

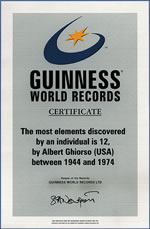

Ghiorso was already a legend when Steve Chu was a student and postdoc at UC Berkeley in the 1970s, Berkeley Lab’s director said in his opening remarks. “He was the man who discovered more elements than anybody except maybe Adam and Eve.” Indeed, Ghiorso’s place in the Guinness World Records as discoverer of the most elements — a round dozen — is unlikely ever to be bested.

Ghiorso chalked up his first pair, elements 95 and 96 (later named americium and curium) in 1944, as a member of Glenn Seaborg’s team at the wartime Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago. Ten more elements followed after his return to Berkeley. His last official discovery, in 1974, was element 106. Twenty years later, after Ghiorso had led a worldwide campaign to recognize his friend and mentor, 106 was named seaborgium.

Bernard Harvey, NSD’s first director, told of Ghiorso’s 1955 invention of the recoil method for capturing individual atoms of new elements. To get irradiated foils from the 60-inch cyclotron on campus to the lab in Building 70, Ghiorso would rush up the hill in his supercharged VW Beetle, past armed guards at the gate who on one occasion, having failed to get a warning phone call, gave chase with weapons drawn.

“Pure luck” was how Norway’s Torbjørn Sikkeland described the discovery of elements 102 and 103, nobelium and lawrencium. Because foils were contaminated by lead, the experiment’s watchword became “get the lead out.” Bob Silva, named the “fastest chemist in the West” for his work with these short-half-life elements, convinced the audience that 102 and 103 were not, after all, the products of luck.

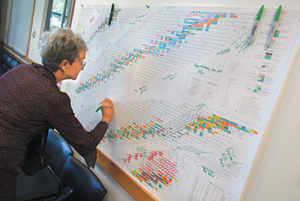

Friends and colleagues signed Al Ghiorsio's wall-sized birthday card -- a chart of the nucleides with all the elements and isotopes he discovered circled.

Friends and colleagues signed Al Ghiorsio's wall-sized birthday card -- a chart of the nucleides with all the elements and isotopes he discovered circled.

Bill Barletta, director of the Accelerator and Fusion Research Division (AFRD), introduced speakers who stressed Ghiorso’s accelerator and detector inventions. The discovery of element 106 with the SuperHILAC was one result.

Jose Alonso, recently of AFRD, said that in 1974 Ghiorso was eager to use a new kind of detector to search for superheavy elements like 114, but Seaborg goaded him to looking for “just one more element the old-fashioned way,” mentioning that Ghiorso’s Soviet arch-rival, G.N. Flerov, was going for 106. The SuperHILAC was soon making 106 atoms, aided by experimental apparatus including ritual candles and Go-Kart inner tubes. Carol Alonso, a recent retiree from Lawrence Livermore Lab, told of the Oak Ridge meeting where Flerov’s data-free claim to have discovered 106 launched a 20-year controversy.

Joining Ghiorsio for a group photo were 11 of his close collaborators and symposium speakers. Left to right are Carol Alonso, Peter Armbruster, Torbjørn Sikkeland, Darleane Hoffman, Art Poskanzer, Al Ghiorsio, Jose Alonso, Bernard Harvey, Walter Loveland, Bob Silva, Kari Eskola, Pirkko Eskola.

Joining Ghiorsio for a group photo were 11 of his close collaborators and symposium speakers. Left to right are Carol Alonso, Peter Armbruster, Torbjørn Sikkeland, Darleane Hoffman, Art Poskanzer, Al Ghiorsio, Jose Alonso, Bernard Harvey, Walter Loveland, Bob Silva, Kari Eskola, Pirkko Eskola.

The symposium’s last speaker was Peter Armbruster of Germany’s Gesellschaft für Schwerionenforschung (GSI), leader in the search for new elements since the 1970s, whose discoveries he described. Armbruster’s appreciation of Ghiorso reflected the respect of both a colleague and a competitor.

GHIORSO’s 90TH: THE PARTY

Among the gifts Ghiorso received was a Burmese jade peacock art piece from longtime collaborator James Wu, formerly of Burma.

Among the gifts Ghiorso received was a Burmese jade peacock art piece from longtime collaborator James Wu, formerly of Burma.

Many speakers recounted Ghiorso’s distinctive way of doing science. Bob Schmieder, who shared the SuperHILAC, noted that “whether the shift was 8, 16 or 24 hours long, all the data was collected in the last 30 minutes.” Bill Myers recalled a student who needed to calibrate a detector with an alpha-particle emitter; Ghiorso asked “Will californium do?” and when the student said yes, Ghiorso stuck his (highly contaminated) thumb on the detector.

Presents included a 57-million-year-old fossil bird from GSI’s Peter Armbruster, commemorating Ghiorso’s dedicated bird-watching, and a hand-carved Norwegian troll from Torbjørn Sikkeland, “because it reminds me of you: a troll is a magician who never dies.”

Ghiorso devoted a moving reminiscence to Wilma Belt, the woman he married shortly after Pearl Harbor, who changed his life in many ways, and who died earlier this year.

At the luncheon’s close, Rick Gough of AFRD presented flowers to the General Sciences staff who made Ghiorso’s 90th a success: Martha Condon, Olivia Wong, Cathy Thompson, Sam Vanacek, and the “mind-boggling” and indefatigable Dianna Jacobs.

Director Chu: My View

Ray Orbach Gives Us a Safety Wake-up

When the Department of Energy’s Office of Science Director, Ray Orbach, made his annual site visit to Berkeley Lab on June 24, he made it a point to schedule a meeting with the Berkeley Lab Safety Review Committee and other safety subcommittees. With 20 of us crowded around my conference table, Ray delivered a message that can best be described as sobering.

He expressed his disappointment with the Lab over the past few months in terms of our accident statistics and his earnest desire to see us return to our former stature as a “star” in the safety world. In 2004, we had the best record. Now we have one of the highest accident rates. “The nature of these (incidents), as I see them, is frightening,” Ray told us.

As of June 1, the rates of our total recordable cases (TRC) and Days Away and Restricted Time (DART) for accidents were both higher than the fiscal year targets established in our report to the University of California. Our 35 total reportable cases placed us seventh out of nine comparison science labs in the DOE, and our DART rate put us eighth out of nine.

When the Department of Energy’s Office of Science Director, Ray Orbach, made his annual site visit to Berkeley Lab on June 24, he made it a point to schedule a meeting with the Berkeley Lab Safety Review Committee and other safety subcommittees. With 20 of us crowded around my conference table, Ray delivered a message that can best be described as sobering.

He expressed his disappointment with the Lab over the past few months in terms of our accident statistics and his earnest desire to see us return to our former stature as a “star” in the safety world. In 2004, we had the best record. Now we have one of the highest accident rates. “The nature of these (incidents), as I see them, is frightening,” Ray told us.

As of June 1, the rates of our total recordable cases (TRC) and Days Away and Restricted Time (DART) for accidents were both higher than the fiscal year targets established in our report to the University of California. Our 35 total reportable cases placed us seventh out of nine comparison science labs in the DOE, and our DART rate put us eighth out of nine.

“It puts your whole future at risk,” Director Orbach told us. “What the devil is going on?”

A one-day work stoppage at the Molecular Foundry was a sobering reminder to always put safety first.

A one-day work stoppage at the Molecular Foundry was a sobering reminder to always put safety first.

Some of the accidents had to do with subcontractors working on the Molecular Foundry, who are none-theless this site’s responsibility. I called for a work stoppage one day a few weeks ago to remind those workers of the need to work safely.

But beyond the concern about statistics, this is the bottom line: I want my employees healthy when they go home.

I know we all are aware of safety and safe practices. I’ve been preaching this since I arrived last year, and so have all of the division directors. However, something’s not working and our message has not reached down to all of segments of Berkeley Lab. While many employees are working in a safe manner, some people aren’t taking the time to stop and think about their work and their colleagues’ work habits. A strong safety culture does that. You look out for yourself and your coworkers. You fix things that you see are wrong. You encourage the discovery and reporting of organizational weaknesses in safety. We’re not there yet.

There’s a very successful program in Facilities with the acronym WOW — workers observing workers. In it, workers are rated for safety by their fellow workers, not by supervisors or outsiders. After intensive training, a volunteer becomes a safety coach. He or she then approaches other workers on a one-to-one basis and asks permission to observe their work practice. Together they go over a checklist, derived from at-risk behaviors identified in studies of real accidents. Corrections are made if necessary.

The Engineering Division is planning to implement the WOW process soon, and we are looking to see if it makes sense to extend it to other divisions and programs. Other ideas proposed by the Safety Review Committee included intensive EH&S training for all supervisors, especially new ones; division-based instruction for supervisors and managers; and frequent walk-throughs of work areas by supervisors.

You can’t legislate a culture change. It has to happen at all levels of our Lab. And if people need more incentive than their own health and safety, then perhaps they should be concerned for the Lab’s future and whether we remain as University of California employees. Ray reminded us that our new management contract is performance-based. It includes eight categories that will be graded for possible contract extension. Safety is one of them.

“A minimum B-plus score is expected,” he told us. Our current accident rate would earn less than a B-plus. At the end of each year, excellent safety performance can extend our affiliation with the DOE through the University for an additional year. In addition, award fees (i.e., LDRD funds) assessed by the DOE can also be impacted, positively or negatively. We hold our future in our hands.

“I’ve always held Berkeley up as a model,” Ray concluded. “You were the best in the complex. This is a very special place. It’s just awful when somebody gets hurt. I want you to know that we care, and that we appreciate what you do, and how hurt we are that all this has happened.”

To my colleagues in the Berkeley Lab community: let’s consider this a wake-up call. Let’s all adopt a safety culture — not just because Ray Orbach demands it, or because the contract requires it, or because I consider it important. Let’s do it for ourselves.

![]()

Car Show a Classic

For the fourth year in a row, Berkeley Lab greeted “the first day of summer” with a car show that included everything from space-age vehicles and racing cars to truly historic models.

Lab Employee Tests Endurance in 585-Mile AIDS Ride

To celebrate his 50th birthday, Doug Lockhart could have taken his wife up on her offer to rent a boat for the weekend or take friends up to Yosemite. But Lockhart, a special projects manager in the Facilities Department, had something else in mind. Instead of relaxing under the sun, he chose to huff and puff his way up and down steep hills, hot inland valleys, and windy coastlines for seven long and grueling days to be part of AIDS/LifeCycle’s annual 585-mile bicycle ride from San Francisco to Los Angeles.

Doug Lockheart celebrates reaching a landmark along the ride to the finish line.

Doug Lockheart celebrates reaching a landmark along the ride to the finish line.

Good cause aside, Lockhart approached this as a personal challenge. “I wanted to prove something to myself. Can I, at 50, ride so many miles in so many days?”

Alongside 1,600 other riders and 400 volunteer “roadies,” he took off on June 5 on a seven-day journey. The physical challenge was anything but trivial even for the healthy, well-trained Lockhart. For so many of his fellow riders, including many who are HIV-positive (the Positive Pedalers), it was a herculean task.

“Some of the riders are highly likely to need the services that this fundraiser is for, and very soon — yet they toughed it out,” Lockhart says. “Some people struggled with every tenth of a mile, but never gave up. Some rode on bikes barely able to make it around the block, but the roadies kept them mobile and they finished the ride. People carried pictures of loved ones they lost. With enough will power, you can get anything done.”

Lockhart remembers the appropriately-named Quad Buster Hill, the first of many that truly tested the riders — their strength as well as their spirit. “Some of the better riders went up and down the hill three or four times helping people who struggled, sometimes pushing them while riding. There was a true sense of camaraderie among all participants.”

Another highlight, Lockhart say, was the sheer joy of riding through some of the state’s most dramatic scenery. “We went through parts of California I’ve never seen before.”

But this was no sightseeing ride, and the challenge took its toll. By Days 4 and 5, Lockart says, “you start hurting in places you never hurt before.” The closer they got to the end, the more inspiring the ride would become. People lined the streets along the route cheering them on; children gave them candy; and on the last night in Ventura, everyone came together for a colossal candlelight vigil.

On Day 7, with 62 miles to go, Lockhart had a sore throat so bad he couldn’t talk. So did many others, by now suffering the effects of high winds, exposure, exhaustion, and nights spent in leaky tents. Fortunately that’s also when the inspiration to keep pushing kicked in. “No way do you want to get to the closing ceremony on a truck,” Lockhart says.

The riders, he added, were slowing down on purpose the last day. “We didn’t want this to end,” he said, and quipped, “It’s not often that you have thousands of people cheering for you. It will be a while before that happens again for me.”

The event raised a record $6.8 million—$3,200 of it from Lockhart, thanks largely to the generosity of fellow Berkeley Lab employees. You can still help Lockhart raise his contribution to the cause by donating at http://www.aidslifecycle.org/6037.

AIDS/LifeCycle benefits the San Francisco AIDS Foundation and the L.A. Gay & Lesbian Center.

A First Peek Inside the Foundry

"Look at the joints: all perfect." Don Beaton, Berkeley Lab’s construction manager for the Molecular Foundry, points to the neat rows of electrical conduit and piping that run along the ceiling on the fourth level of the Molecular Foundry. On all sides, workers are installing wall framing, utility piping, and ductwork for the wet labs that will make up the Foundry's Inorganic Nanostructures Facility. One floor up, the cold rooms, tissue culture rooms, and dark rooms of Biological Nanostructures are taking shape, and on the top floor more wet labs for Organic Nanostructures are under construction. Throughout the building, utility installation is going well.

The construction of the building is designed to promote a sense of community and collaboration through open "interaction areas,� many of them with spectacular views.

The construction of the building is designed to promote a sense of community and collaboration through open "interaction areas,� many of them with spectacular views.

The Molecular Foundry is one of five Department of Energy Nanoscale Science Research Centers. The building design was very much a team effort, the product of many months of close cooperation between scientists, architects, engineers, and constructors. The result is a facility in which each of six levels is specifically designed to accommodate one of the six nanoscience facilities.

The first-level Imaging and Manipulation Facility is built on a heavy concrete pad to minimize vibration effects on the Foundry's electron microscopes and atomic force microscope. Built partially into the hillside, the second level will also provide a low-vibration pad as well as a clean room with temperature and electro-magnetic field protection for the Nanofabrication Facility's $4-million e-beam writer. Vibration levels on these floors are being monitored during construction to ensure that they meet design tolerance of 125 microinches per second. Electromagnetic interference is being minimized through panel board placement and power routing, and the use of fiberglass- or epoxy-coated rebar.

Tthe Molecular Foundry rises on a hillside overlooking the bay.

Tthe Molecular Foundry rises on a hillside overlooking the bay.

“The intent is for staff scientists to spend half their time on their own research and half collaborating on users' projects,” said Jim Bustillo, the associate director for the Molecular Foundry.

The nanoscale research program is all about collaboration, and the building’s architectural design emphasizes opportunities for interdisciplinary contact, providing "interaction areas" throughout the building. Most notable are the open areas at the western end of each of the top three floors (the inorganic, biological, and organic and polymer labs, respectively) which look out over the bay to the San Francisco skyline, providing "interaction spaces with awesome, living-room-like views," according to Bustillo. Such opportunities for interdiscipinary collaboration, he notes, “are the whole reason for the nanoscale research centers.”

As of now, Foundry construction is on budget and on track to meet its December 2005 completion date, with commissioning in March 2006. This is particularly good news for Bustillo, who is responsible for procuring the foundry’s scientific equipment: “Their running a tight ship means that we’ll be able to increase the technical equipment contingency funds with unused construction contingency to enhance the research capabilities of the Lab.”

An Eventful Month in Berkeley Lab Science

Berkeley Lab researchers have kept up a fast pace of scientific advance over the past month. Here are a few highlights.

Discovering breast cancer molecular pathways

Life Sciences Division researchers and collaborators, led by Mina Bissell and Derek Radisky, discovered a molecular pathway by which an enzyme that normally helps remodel tissues initiates the pathway to breast cancer, by stimulating the production of highly reactive oxygen molecules that disorganize tissues and damage genomic DNA. The July 7 Nature tells the full story.

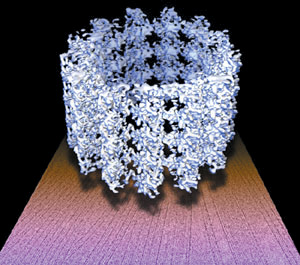

Eva Nogales and Hong-Wei Wang of the Life Sciences Division have discovered the forms taken by transitional structures of tubulin, the protein from which a cell's microtubules are formed, during microtubule assembly and disassembly. In an article in the June 16 issue of Nature, they show how this essential activity is controlled by a single small molecule, guanosine triphosphate.

A sharper focus for x-rays

Soft x-rays from the Advanced Light Source can produce images of structures and their chemical, electromagnetic and other properties. The Materials Sciences Division's Center for X-Ray Optics used a technique devised by Weilun Chao to create zone plates for focusing x-rays having extraordinary resolution — better than 15 nanometers. Details appear in a June 30 letter to Nature.

A study of twins — one a long-distance runner, the other a comparative couch potato — showed a strong similarity in the way the level of "bad" cholesterol in each pair of twins responded to diets that were high or low in fat.

The study, which proves the importance of genes in cholesterol response, was designed by Paul Williams of the Life Sciences Division and appeared in the July 8, 2005, issue of the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

For more information on these and other science stories visit the Lab's News Releases web page.

Life After the Fruit Fly

An Interview with Gerry Rubin

Gerry Rubin, a geneticist in Berkeley Lab’s Life Sciences Division, led a collaborative effort to sequence the genome of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, which was completed in 2000. Next summer, Rubin is moving to Virginia to head a new Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI)-funded research center dedicated to exploring biology’s unanswered questions, such as how the brain works. He’ll leave behind the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project, a 40-strong group of scientists who are analyzing the vast amount of information derived from the sequencing of the fruit fly genome. Rubin is also a professor in UC Berkeley’s Department of Molecular and Cell

Why sequence the fruit fly?

How can the fruit fly help scientists better understand human diseases?

More than two-thirds of human disease genes have a corresponding gene in the fruit fly. This is good news, because after scientists isolate a human disease gene, the next challenge is to determine the biochemical mechanism it’s involved in. Fortunately, we can much more easily discover a gene’s function in fruit flies than in humans, which will inform our understanding of the human disease. There are dozens of examples of how this has already advanced our understanding of cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.

What strengths do big multidisciplinary labs like Berkeley Lab bring to genome research?

There are several reasons why the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project couldn’t have been done in Berkeley if the Lab didn’t exist. Berkeley Lab is used to providing large amounts of space to projects that have a short duration. At our peak, we had nearly 60 people at Berkeley Lab working on the project, and there is no way you can get that kind of space on campus. Secondly, in the early days, we had to build our own automation methods, and the engineering and robotics expertise at Berkeley Lab was extremely useful. Most of our high-throughput work was done here.

Genomics is also an information-based science. Our team must interpret how the information encoded in that string of A G, C, and Ts makes a fruit fly. We also have tens of thousands of images in our database showing different gene expression patterns, and we have a very active software group dedicated to displaying and analyzing these data, often in collaboration with other groups at the Lab and on campus.

What’s next in the fruit fly project?

I’m heading in a new direction, but the project is alive and well. There is a very active program at Berkeley Lab that continues to explore how the fruit fly genome works. Garry Karpen is leading a group that is studying the heterochromatin, the portion of the genome that is very complicated and located near the centromere. Another big challenge is determining the structures and functions of genes and how they’re expressed. In this vein, Susan Celniker is leading a group that is developing a functional interpretation of the genome. And Mark Biggin has a grant to study gene networks during embryogenesis.

What’s next for you?

My research has been supported by HHMI since 1987, and in 2000 I became a vice president at HHMI and have been splitting my time be-tween here and Chevy Chase, MD. Next summer, I will leave Berkeley to head HHMI’s first intramural research center, the Janelia Farm Research Campus, which is located in Virginia. The lab will delve into very long-range basic research in an environment where scientists are encouraged to take risks — kind of like a Bell Labs for biology. We’ll take on projects that we don’t know will work in ten years. Specifically, we are interested in learning how the nervous system works, and developing new optical imaging methods to facilitate this research. We will bring together 400 scientists, including biologists, neuroscientists, geneticists, physicists, computer scientists and computational biologists.

What about the next 100 years?

To do this, we have to be able to see what the neurons are doing in real time at a single-cell resolution while the fruit fly brain is working. And just as we have tools to study genetic pathways in the fly, we are developing tools to study nervous system function. Such techniques include using genetically engineered neurons that fluoresce when they activate. The small size of the fly brain also means the entire brain is optically transparent and easy to image. This work should yield some basic rules that will be applicable to humans over the next 20 to 30 years.

Orbach Visits Berkeley Lab Facilities

Office of Science Director Ray Orbach and Berkeley Lab Director Steve Chu launch a new network with a symbolic connecting of wires.

Office of Science Director Ray Orbach and Berkeley Lab Director Steve Chu launch a new network with a symbolic connecting of wires.

Photo by Roy Kaltschmidt, CSO

In a ceremony reminiscent of the 1869 event in which a final golden spike completed the trans-continental railway, Orbach and Lab Director Steve Chu launched the network by connecting two wires — one linked to the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), the other to the network, which is part of DOE’s Energy Sciences Network (ESnet).

The network links the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, Berkeley Lab, the Joint Genome Institute, NERSC, and Lawrence Livermore and Sandia National Laboratories at substantially reduced cost. By increasing bandwidth to these sites, the new metropolitan area network (MAN) will help advance research in areas such as climate change, genetics, renewable energy, nano-technology, national security, and physics and chemistry.

“Scientists at our national laboratories need the best available technologies to conduct their world-class research,” said Orbach. “This new network provides a necessary, cutting-edge resource for researchers as they seek to understand important subjects, such as the development of sustainable energy sources as well as the creation and evolution of the universe.”

Orbach also toured the Potter Street Biosciences Facility, the Lab’s new address for multidisciplinary research in synthetic biology, cell and molecular biology, cancer research, and quantitative biology. Then it was up the Hill to the venerable Advanced Light Source (ALS), where Orbach lunched with ALS users. His tour ended with a discussion of the future of plasma-wave accelerators and applications with Wim Leemans of the Center for Beam Physics in the Accelerator and Fusion Research Division.

People, Awards, and Honors

Kramer Earns NASA Award

The AATT Project was completed in 2004 after nine years of highly successful research, development and technology transfer to the FAA and the airline industry. The major focus of the AATT Project was to improve the capacity of transport aircraft operations at and between major airports in the National Airspace System (NAS) by developing decision support tools and concepts to help air traffic controllers, airline dispatchers, and pilots improve the air traffic management.

Stacy Receives Teaching Award

Angelica Stacy, a scientist in the Materials Sciences Division and a UC Berkeley professor, was honored by the National Science Foundation (NSF) as a Distinguished Teaching Scholar on June 22. Stacy is one of seven leaders in research and education who received the award for both groundbreaking scientific results and major educational contributions “evidenced by their strong teaching and mentoring skills," according to the NSF. The awards, worth up to $300,000 over four years, were presented in a ceremony at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C.

Tsang Wins Rock Mechanic Award

In Memoriam: Fred Vogelsberg (1924-2005)

A long-time engineer at Berkeley Lab who retired in 1989, Fred Vogelsberg died peacefully in his sleep on May 8. He was 81.

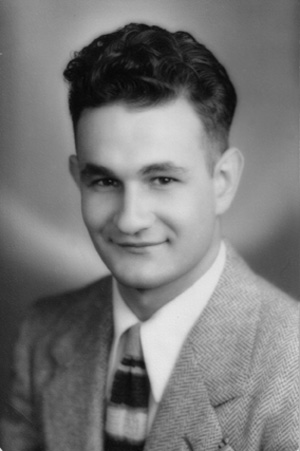

From his Navy days, Berkeley Lab engineer Fred Vogelsberg gained a love of the sea that led him to become a Commodore at the Richmond Yacht Club.

From his Navy days, Berkeley Lab engineer Fred Vogelsberg gained a love of the sea that led him to become a Commodore at the Richmond Yacht Club.

Born in Michigan in 1924, Vogelsberg came to California with his parents at the age of three and grew up in San Gabriel. He attended Pasadena Junior College until 1943, when he enlisted in the Navy. Upon his discharge after World War II, he returned to Pasadena, completed his studies, and then entered UC Berkeley. He received his BA in electrical engineering in 1950. After brief stints at McClellan Air Force Base in Sacramento and Rogers Engineering Company in San Francisco, he joined the staff at Berkeley Lab in 1952, where he worked until his retirement.

Vogelsberg will be remembered by veterans of the Nuclear Science Division for his work on the Pulse- Height-Analyzers, and by MSD researchers for his work on radio-frequency induction heaters and large ellipsometer magnets. Probably his most notable accomplishment, however, was his contribution to the Nobel Prize-winning crossed molecular beam research of Y.T. Lee.

Said Katz, “The instruments that Fred was responsible for enabled Lee and his group to perform experiments that no one else in the world could do at that time.”

Fred Vogelsberg is survived by his wife of 52 years, Louise, daughter Linda Vogelsberg Beroza and her husband Paul, and one grandchild.

Berkeley Lab View

Published twice a month by the Communications Department for the employees and retirees of Berkeley Lab.

Reid Edwards, Public Affairs Department head

Ron Kolb, Communications Department head

EDITOR

Monica Friedlander, 495-2248,

[email protected]

STAFF WRITERS

Lyn Hunter, 486-4698

Dan Krotz, 486-4019

Paul Preuss, 486-6249

Lynn Yarris, 486-5375

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Jon Bashor, 486-5849

Allan Chen, 486-4210

David Gilbert, (925) 296-5643

FLEA MARKET

486-5771, [email protected]

Design

Caitlin Youngquist, 486-4020

Creative Services Office

Berkeley Lab

Communications Department

MS 65, One Cyclotron Road, Berkeley CA 94720

(510) 486-5771

Fax: (510) 486-6641

Berkeley Lab is managed by the University of California for the

U.S. Department of Energy.

Online Version

The full text and photographs of each edition of The View, as well as the Currents archive going back to 1994, are published online on the Berkeley Lab website under “Publications” in the A-Z Index. The site allows users to do searches of past articles.

Flea Market

- AUTOS & SUPPLIES

- ‘86 TOYOTA CAMRY, low mileage, orig owner, 5 sp man, $1,300, Harvey, X7777

‘76 CHEVROLET MALIBU CLASSIC, white, 4 dr, cloth seats, good cond, runs great, 2nd owner, $3,500, Norma, 530-9537

‘68 MERCURY MONTEGO, 135K mi, 302 V8, auto, blue w/ blk vinyl roof, runs well, body/paint/upholstery/tires in good cond, $2,500, Brian, X4677, 524-8259 - MOTORCYCLES

‘95 HONDA SHADOW 600, purple & blk, 4 stroke, 9500K mi, 2nd owner, tags & reg good till 6/06, $1,500, Mario, X5353, 2209

- HOUSING

- ALAMEDA, 2 bdrm/1 bth apt in Victorian bldg, hardwd flrs, built-in china cabinet, remod kitchen, on third floor w/ bay view, laundry rm, avail 7/9, no pets/smok, nr shop ctr/beaches/pub trans, $1,295/mo, 895-3584, [email protected]

ALAMEDA, 1 bdrm/1bth apt, high ceilings, updated kitchen, new carpets, Victorian bldg, nr shopping ctr, beaches/trans, corner unit w/ lots of light, no pets/smokers, $985/mo, 895-3584, [email protected]

BERKELEY, resid community of scientists/ staff/grad students, 1146-1160 Hearst, nr UC/trans, parking, internet, studio townhouses w/ decks, hardwd flrs, skylights, dw, intercom, sec, from $850, Andrew, 848-5371, Lizy, 435-4958, view units at http://www.live-work.us/

BERKELEY HILLS, fully furn rm w/ sep entry, full kitchen privil, w/d, quiet neighbd, backyard, next to bus stop, avail now, [email protected], 524-3851

BERKELEY HILLS, Campus Dr/top of La Loma, rm w/ priv ent, 10’x 13’, lge deck, surrounded by trees, hill view, priv bthrm, furn, shared DSL & cable, kitchenette, no smok/pets, refs/credit check at appt, move-in discount by 7/15, $760/mo+25% of util, sec dep, 1-yr lease, Rozalina, 845-4624

CENTRAL BERKELEY, sm 1 bdrm house, new kitchen, yard, some util incl, $1,150/ mo, [email protected], 845- 5959

EL CERRITO HILLS, priv rm in shared house, lge bedrm w/ bay view, walk-in closet, internet, share lge liv rm, backyrd, 2 bthrms & laundry w/ 3 housemates (30-40), 2 fem/1 male, 2 cats, str parking, avail from 8/1, $520/mo+utils, Cinthia, X2889, 932-9186

KENSINGTON, fully furn 3 bdrm home, view, quiet setting, 1 cat, avail for visiting scientist during July/Aug, $1,400-1,600/mo +sec dep, Ruth, 526-2007, 526-6730

KENSINGTON, furn rm for fall semester, own 1/2 bth, kitchen & laundry, $550/mo, Ruth, 526-2007, 526-6730

MARINA BAY, unfurn condomium, 2 bdrm/2 bth, balcony, fireplace, bay view, w/d, covered sec parking, cats only, no smok, $1,200/mo, Sally, X5875, 235-6354

NORTH BERKELEY B&B, breakfast daily, 3 furn rms, $550/mo, avail immediately, short or long term, Helen, 527-3252

NORTH BERKELEY, quiet, furn rm in historic brown shingle, all amenities, wireless internet, walk to BART, Lab shuttle, downtown & shops, limited kitchen privil, avail 9/1, short or longer term, $500/mo, Rob, 843-5987

OAKLAND, 3 bdrm/1.5 bth, nice location, lge priv yard, full basement w/ laundry rm, fp, newly renov, nr fwy, $1,300/mo, 1st/last+clean dep $1,000, Ignacio, X6026

PLEASANT HILL, spacious 3 bdrm/2 bth townhouse, 2-car garage, community pool & facilities, short drive to shops/BART, $1,600/mo, Derun, [email protected], X 5053

WALNUT CREEK townhouse, Cannon Dr, 2 bdrm/2.5 bth, garage, w/d hookup, central ac, 2 patios, pool, tennis, $1,400/mo, Bob, (925) 376-2211, [email protected] - HOUSING WANTED

- EAST BAY, 1 bdrm furn apt needed Aug & Sept for adult couple, visiting prof from Tel Aviv, Isreal, Joe, 845-5580, jekatz@ ieee.org, or [email protected]

BERKELEY HILLS, house or apt wanted 10/1 – 11/30/05, dates flexible, 2 bdrms, clean, full kitchen, nice views, for in-laws visiting from Germany, Alexis, 207-9890

Visiting Swiss grad students, two males, Aug-Oct 2005, can share if appropriate, C. Haber, X7050

Austrian researcher arriving 9/1, seeks Berkeley or nearby rm/small studio, $800/mo max, pref priv bth, full/partly furn, nr BART, Chris, X7028, 848-2389 - MISC ITEMS FOR SALE

- ALTO SAXOPHONE, Selmer Bundy II, w/ case, good cond, $150, Olivia, X4182, 233-1088

BEDROOM FURN, solid pine, exc cond, translucent white finish, queen futon bed w/ twin bunk bed over 2 chests of drawers, corner unit & small desk, matching heights, bookcase & oval mirror, will sell sep, $30 – $250, pref to sell as set, price neg, Rosemary, (925) 229-4275

BEDS, 2 twin size, good cond, $25 each, small desk $10, Bob, X6162, 357-2778

BOOKCASE, teak, drop-lid, 30"wx16"dx 75"h, $35; beige lacquer dresser, 62"l x 29"h x 17"d, $50, Sue, 595-7123

China Dinnerware for 8, Cordon Bleu Bia, micro & dw safe, blue pattern, incl various size bowls, serving platters, salt/pepper shakers, 2-coffee cups, $175 for set; dish network, 2 PVR, receivers & antenna w/ non-perf mount $125; 2-quart corningware baking dish w/ pyrex lid & storage lid, $2 ; lge steamer w/ 2 stacking trays & lid $5; NESCO food dehydrator, used, $25, Daniel or Tarise, 845-5462

PINE SHELVES, 160 CDs, $10; 200 CDs $15; 2 dining tables, 36x48 extends to 78, $30; butcher blk, tbl, 26x48x12, $20; workstation, 23x36 on casters, $25, Joe, X7284

SKIS AND FISHING ROD, 2 prs of skis,

SPORT RIDER, HealthRider, good cond, $70, photo avail, X5573 - FREE

- QUEEN-SIZE BOX SPRING, twin-size mattress & box spring in good cond, you pick up, Tamas, X5808

- WANTED

- HOME STEREO type CD player w/ carousel style load tray, Bill, X4466, 292-5253

USED BRICKS for landscaping project, I'll pick up, Dianne, 528-9402