BP Makes Berkeley World Center for Biofuels

The BP Back Story: A Mission Possible

BP Makes Berkeley World Center for Biofuels

Governors of California and Illinois Help Make the Announcement

Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger addresses the crowd gathered for the announcement of the BP grant. Seated from left to right are UC Berkeley Chancellor Robert Birgeneau, UC President Robert Dynes, Illinois Vice Chancellor Charles Zukoski, Berkeley Lab Director Steve Chu, and BP’s Steven Koonin. Photo by Roy Kaltschmidt, CSO

Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger addresses the crowd gathered for the announcement of the BP grant. Seated from left to right are UC Berkeley Chancellor Robert Birgeneau, UC President Robert Dynes, Illinois Vice Chancellor Charles Zukoski, Berkeley Lab Director Steve Chu, and BP’s Steven Koonin. Photo by Roy Kaltschmidt, CSO

Unless you’ve been hunkered down in the SNO cave, huddled above the IceCube, flung out on the cosmic edge of dark energy, or in some other fashion far-removed from the local scene, you’ve heard the news: Berkeley Lab is a member of a partnership with UC Berkeley and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign that won a stiff competition for a $500 million grant from global energy giant BP. The purpose of this grant, over the next 10 years, is to establish a mission-specific research center called the “Energy Biosciences Institute (EBI). The specific mission of EBI is to develop new and cleaner sources of energy from biomass (plant and other organic material), principally biofuels for transportation.

California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and Illinois Governor Rod Blagojevich came to UC Berkeley’s Clark Kerr campus on Thursday, Feb. 1, to join Robert Malone, chairman and president of BP America for the announcement. Accepting the award were Berkeley Lab director Steve Chu, UC Berkeley Chancellor Robert Birgeneau, and Charles Zukoski, Vice Chancellor for Research at the University of Illinois’ Urbana-Champaign campus. Also making remarks at the announcement ceremonies were UC President Robert Dynes, BP Chief Scientist Steve Koonin, and California State Senate President Pro Tem Don Perata and State Senator Dick Ackerman.

Said Governor Schwarzenegger at the ceremonies, “California is not waiting for a clean-energy revolution. No — we are actually the leaders in the revolution.”

Lab Director Chu has been one of the most outspoken public advocates for biofuels research. In response to the announcement of the BP grant he said, “This partnership with BP will develop new sustainable energy technologies that can transform the landscape. We believe EBI will create a culture where vibrant interpersonal interactions will generate extraordinarily innovative energy research. The team science approach introduced by Ernest O. Lawrence 75 years ago and the invention of the transistor at Bell Labs are striking examples of how large-scale, multidisciplinary problems were solved by establishing the proper scientific culture where the most brilliant minds can work together.”

The BP press conference: from left, Robert Birgeneau, Robert Dynes, Charles Zukoski, Steve Chu, Steven Koonin, and Bob Malone

The BP press conference: from left, Robert Birgeneau, Robert Dynes, Charles Zukoski, Steve Chu, Steven Koonin, and Bob Malone

Chancellor Birgeneau called the quest for new energy sources that are sustainable, commercially viable and environmentally clean, “our generation’s moonshot.” He added, “We are tremendously excited at the possibility this EBI partnership holds for solving one of the most fundamental problems that currently faces our nations and the world.”

The “BP” brand long stood for “British Petroleum,” but in 2005, the company announced it would stand for Beyond Petroleum, to signify the need to develop new fuels that can supplement traditional hydrocarbon sources. In keeping with this vision, the company announced last June that it planned to invest $500 million over a 10-year period in the EBI, and in October, it invited five universities, including UC Berkeley in partnership with Berkeley Lab, to submit plans for hosting this institute. Other competitors included MIT, Cambridge University, the Imperial College of London and UC San Diego.

Chu in a media interview

Chu in a media interview

UC Berkeley boasts nationally recognized programs in molecular and cell biology, chemistry and both chemical and genetic engineering. It also has social scientists who understand the societal, business, legal and ethical implications of switching from gasoline to biofuels. For its part, Berkeley Lab brings state-of-the-art facilities such as the Molecular Foundry, the Advanced Light Source and the Joint Genome Institute, plus decades of experience in energy research. Together, Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley are at the forefront of synthetic biology and nanoscience, and have also fostered leading studies on global warming and its impact. The University of Illinois was added to the partnership because of its expertise in genetics and agronomy, and its experience at testing sustainable agricultural practices.

Birgeneau and Dynes field questions

Birgeneau and Dynes field questions

“The Berkeley proposal was selected in large part because these institutions have excellent track records of delivering Big Science — large and complex developments predicated on both scientific breakthroughs and engineering applications that can be deployed in the real world,” said BP Group Chief Executive Lord John Browne. “This program will further both basic and applied biological research relevant to energy. In short, it will create the discipline of energy biosciences. The EBI will be unique in both its scale and its partnership between BP, academia and others in the private sector.”

EBI research will initially focus on three critical areas for the conversion of biomass into biofuels. First will be the development of plant feedstocks that are better-suited for biofuel production than the conversion of corn into ethanol that is being practiced today. Next will be the development of new techniques for breaking down plant material into its sugar building blocks. And finally, there will be a search for new ways to ferment sugars into ethanol or other forms of biofuel such as butanol, which has the potential to be used in today’s cars without any change to the engine.

Chu speaks to those gathered for the press conference

Chu speaks to those gathered for the press conference

Berkeley Lab Deputy Director Graham Fleming, one of the principals behind the winning BP proposal, said of the EBI research, “We’re not going to have any vested interest in a particular outcome. We’re going to draw on the best science and information to come up with an unbiased analysis of where the opportunities are, what the problems are, and then what the solutions to those problems are. I see this institute as integrating all the disciplines, including social sciences and economics, to really make sure that we have seen the whole picture and understand and can balance the various approaches on a rational basis.”

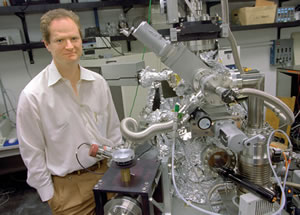

Jay Keasling educates a reporter

Jay Keasling educates a reporter

EBI research is scheduled to get underway in July. Participating researchers will initially be housed on the UC Berkeley campus, primarily in the Calvin Laboratory. Last December, Governor Schwarzenegger and California State Assembly Speaker Fabian Nunez pledged that if BP awarded the EBI to UC, the state would add $40 million more for a building. These funds will be combined with another $30 million from the state towards a new research building at the Lab, near the campus border. The new building will be the home to both EBI and Helios, Berkeley Lab’s own initiative to develop solar-based, carbon-neutral energy technologies.

Energy Biosciences Institute (EBI) commemorative pins

Energy Biosciences Institute (EBI) commemorative pins

Said Lab Director Chu, “It takes more than scientific innovation to create environmentally friendly solutions to the energy problem. Governor Schwarzenegger, President Pro Tem Perata, Speaker Nunez, and the State Legislature have made California the leader in energy policy and energy conservation in the U.S., and now, with their support, California will lead in energy research on clean sustainable alternative energy sources.”

The BP Back Story: A Mission Possible

An event this big, this dramatic, generally has an interesting back story. And this one was a doozy.

The tale of the Energy Biosciences Institute unraveled like a “Mission Impossible” script: Your assignment, should you choose to accept it, is to develop a comprehensive, competitive proposal for a half-billion-dollar research center — which would traditionally take about a year and a half — in six weeks.

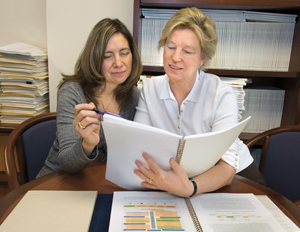

Diane Leite, left, deputy director of the Berkeley campus QB3 program, and Ann Jeffrey, Assistant Vice Chancellor for Research, the two campus staff leads for the BP proposal effort.

Diane Leite, left, deputy director of the Berkeley campus QB3 program, and Ann Jeffrey, Assistant Vice Chancellor for Research, the two campus staff leads for the BP proposal effort.

Uh, sure, said Diane Leite, deputy director of the Berkeley campus’ QB3 program. Right, said Assistant Vice Chancellor for Research Ann Jeffrey. Thus the two field generals for this full-scale assault on academic bureaucratic deliberation set out to make believers of us all, with a little help from their friends.

“We never thought it couldn’t be done,” said Leite, whose navigation of weekly Thursday planning meetings was military-efficient and prize-focused. “We always get things done. But we felt like the underdog coming in. It was a big commitment, but would it be for nothing?”

The competition came in with strengths in facilities and partnerships, and reputations to match — MIT, UC San Diego, Imperial College, and Cambridge. Berkeley was land-limited, its buildings filled to capacity.

But in the end, it had what BP needed — Nobelist Steve Chu of Berkeley Lab, whom Berkeley Chancellor Bob Birgeneau calls “our messiah” and whose vision is generally credited with paving the way for EBI’s success; bioscientist Jay Keasling, whose synthetic biology innovations set the standard for transformational science; a Who’s Who of great minds in multiple fields from both campus and lab; and research facilities unlike any other, featuring cutting-edge technologies that developing an entirely new fuel source will require.

And that team. In any given week, the ground forces numbered 20 to 30. From Oct. 16, when energy giant BP issued its request for proposals, to Nov. 27, when Leite dropped the Fed-Ex package of hard-cover packets into a box bound for BP’s Houston headquarters, lives were unhinged and sleep went on a holiday. Example: Jeffrey says “the biggest single challenge was finding a mutually acceptable sandwich shop that we could order out from on Sundays.” Leite barely had enough time to eat Thanksgiving dinner with her family at the Pinole Creek café.

There are many sung and unsung heroes in this story. At the top were the relentless drives of Chu and Birgeneau and their deputies, Vice Chancellor Beth Burnside and Lab No. 2 Graham Fleming. Jay Keasling, Leite says simply, was “exceptional,” from the late-night-sandwich Potter Street rewrites, to the all-night presentation prep in London, to his five-star performance the next morning before the BP panel.

From the Lab, strategic planning director Mike Chartock led the effort to make sure the facilities pitch — including a new Helios building at the Lab — was persuasive. Don Medley, who with campus colleague Michelle Moskowitz formed a relentless government relations tag team, ensured that industry and state support were strong and that the Governor’s commitment of funding arrived on time to anchor the proposal.

Creative Services editor Bruce Balfour became Keasling’s go-to guy for content in the science portion of the proposal. Nancy Padgett and Kristin Balder-Froid kept their respective bosses, Chu and Fleming, up to speed on developments and needs. Designer Cait Youngquist’s poplar-leaf image concept became the visual centerpiece of the EBI.

“We marveled at how everyone pulled together,” Jeffrey said, “every level of the team, from deans and vice chancellors to all the support staff. It wasn’t just a few — everyone chipped in. There was incredible energy to this project that you almost never see in your life.”

Leite and Jeffrey are just now getting back to their lives’ normal rhythms and to husbands who they both say were “forgiving.” Leite’s 13-year-old son will now have his mom back to help with homework, at least for the time being.

In the wash of emotions following BP’s announcement on Feb. 1, Chancellor Birgeneau told members of the proposal team that BP had made a definitive statement — “that UC Berkeley is simply the best public institution in the world. Period.” And to that, Fleming added, “Together (campus and Lab), nothing can stop us.

Second-Generation Lab Employee Continues Legacy by Leading UC Staff Organization

Bill Johansen has been coming to the Lab for nearly 37 years … and he’s only 36 years old. Johansen’s mother, Patricia, while pregnant with her son, came often to the Hill to visit his father, Walter, who began his 41 years of Lab service as a tool-and-die maker. The younger Johansen’s birth would later be announced in the “Magnet,” the employee newspaper at that time.

Bill Johansen.

“I can remember running up and down the stairwells of the Building 50 complex as a kid,” recalls Johansen, senior business manager for the Life Sciences Division. “I was also here for the first-ever Runaround in 1978.”

Johansen started working at the Lab himself as a high school student in 1987, and continued while in college at Cal. A political science major, he spent a couple years in Washington D.C. after graduation, but came back to the Lab in 1996 and has been here ever since.

With such strong connections to the Lab, it’s not surprising that Johansen has found a way to help improve the work experience for others. In 2003, at the urging of a colleague, he signed up to be a member of the Council of University of California Staff Assemblies, or CUCSA, as one of Berkeley Lab’s delegates. In 2005, he was voted chair-elect, and is now serving as chair.

Bill Johansen, center, with his mother Patricia, father Walter, and sister Pam in 1978 at the Lab’s first Runaround.

Bill Johansen, center, with his mother Patricia, father Walter, and sister Pam in 1978 at the Lab’s first Runaround.

CUCSA is comprised of delegates from every UC-managed institution. They discuss issues that affect staff with top UC administrators and Regents. CUCSA members are also asked for their feedback on programs and initiatives that UC is developing.

“I joined CUCSA because I felt it was important for decision makers to get input from staff on issues that will affect them,” explains Johansen. “It has taken time, but we have established ourselves as an integral part of UC’s administrative process.”

One major program CUCSA worked on for the past decade was getting a staff member seated with the Regents at their meetings. Success was finally achieved when the Staff Advisor program was officially adopted in January, after a two-year pilot program.

Current issues CUCSA is working on include preparing for the mass exodus of thousands of UC employees over the next several years due to retirement and how their knowledge will be transferred to new generations of workers. Another project involves increasing and sustaining diversity in the workforce.

“This group has had a real impact and become part of UC’s fabric,” says Johansen. “But we need new recruits to come in and build upon the successes we’ve achieved.”

Nominations are currently being accepted for the Lab’s 2007-2008 junior CUCSA delegate, to serve alongside a senior delegate. The Lab’s current delegates are Liz Moxon (senior) and Jeff Troutman (junior), both with the Advanced Light Source.

Upcoming CUCSA Programs

Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley are co-hosting CUCSA’s spring meeting March 7-9. Members will meet on campus on Thursday, March 8 and at the Lab on Friday, March 9 from 9 a. m. to 4 p.m. in Perseverance Hall. Staff are invited to attend either day.

Those interested in becoming a CUCSA delegate can submit their nomination at www.lbl.gov/Workplace/Ops/cucsa.html. Full-time, non-represented career staff with at least five years of satisfactory performance with UC are eligible. The deadline is March 31.

For more information on CUCSA, contact Liz Moxon (x5760) or Jeff Troutman (x2001).

Staff interested in serving as the next Staff Advisor to the Regents can visit www.universityofcalifornia.edu/staffadvisors to learn more and apply. Application deadline is Feb. 28.

From Buckyballs to Manta Rays: The Diving Adventures of an ALS Beamline Scientist

There sat Fred Schlachter on the dark ocean floor, 36 feet below the surface. Just an arm’s length away swam a manta ray. Though elated at the sight of this magnificent creature, visions of Steve Irwin — the Australian TV show host who died last fall from a stingray’s stab — flashed before him.

Schlachter heads out to the Similan Islands near Thailand for a dive.

But this was not Schlachter’s most frightening underwater experience. One time, the avid scuba diver’s goggles completely fogged at a depth of 110 feet, which prevented him from checking his depth, submersion time and air pressure.

“It’s important to be able to see the ascent rate to come safely to the surface,” he explains. “It was scary not being able to read my instruments, so I had the divemaster escort me back up to the surface.”

And that’s the closest Schlachter, a beamline physicist for the Advanced Light Source, has ever come to a problem in his 10 years of scuba diving.

Schlachter has dived in the Great Barrier Reef, the Caribbean, and the Indian Ocean, as well as the waters off Brazil, Vietnam, Bali and Hawaii. And he hopes to reach Palau (South Pacific) and the Red Sea at some point in the future. However, his most frequent destination is the Andaman Sea off the coast of Thailand. Schlachter is on the faculty at Chiang Mai University, where he lectures in the physics department and mentors a Ph.D student.

Schlachter is careful to leave plenty of distance between himself and a leopard shark in the Andaman Sea.

When he’s not diving, the 31-year Lab veteran is assisting ALS users. He researches “how electrons give atoms and molecules their properties, and how big an atom has to be to begin to behave classically, as opposed to quantum mechanically.” He was also involved with the search for quantum chaos and collective oscillation of electrons in buckyballs.

But every now and then, Schlachter must leave the chaos and oscillation of work behind and head for the quiet calm of the world’s oceans in search of fascinating fish. Like the six-foot-long leopard shark he was photographed with last fall in the Andaman Sea.

“They are generally docile and easily approached as long as they’re not startled,” he said. “Though the photographer was urging me to get closer, Steve Irwin’s death reminded me to keep my distance.”

Despite the stories of divers caught in fishing lines or kelp, running out of air, or getting left behind in the open seas, Schlachter says diving is very safe.

“Proper training, certification and equipment, following procedures and diving with a professional divemaster keeps mishaps to a minimum,” says Schlachter. “Funny, this kind of sounds like how we work safely at the Lab.”

Berkeley Lab View

Published once a month by the Communications Department for the employees and retirees of Berkeley Lab.

Reid Edwards, Public Affairs Department head

Ron Kolb, Communications Department head

EDITOR

Pamela Patterson, 486-4045, [email protected]

Associate editor

Lyn Hunter, 486-4698, [email protected]

STAFF WRITERS

Dan Krotz, 486-4019

Paul Preuss, 486-6249

Lynn Yarris, 486-5375

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Ucilia Wang, 495-2402

Allan Chen, 486-4210

David Gilbert, (925) 296-5643

DESIGN

Caitlin Youngquist, 486-4020

Creative Services Office

Berkeley Lab

Communications Department

MS 65, One Cyclotron Road, Berkeley CA 94720

(510) 486-5771

Fax: (510) 486-6641

Berkeley Lab is managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy.

Online Version

The full text and photographs of each edition of The View, as well as the Currents archive going back to 1994, are published online on the Berkeley Lab website under “Publications” in the A-Z Index. The site allows users to do searches of past articles.

Flea Market is now online at www.lbl.gov/fleamarket

A Gene Expression Spectacular: the Developing Drosophila Embryo

Two hours after the egg is fertilized, the embryo of Drosophila melanogaster reaches the blastoderm stage, during which the future fruit fly’s development is a hotbed of activity. Some 6,000 distinct nuclei in the egg’s single cell migrate to the surface, where they are enveloped by membranes and, within about half an hour, become individual new cells.

The blastoderm’s shape remains like that of the egg, a smooth if somewhat irregular ellipsoid, but this simplicity will soon be lost: at the next stage of development, called gastrulation, the embryo begins to crease, eventually folding into the fly’s intricately articulated body plan. Meanwhile, uncomplicated geometry and the fact that the nuclei and resulting cells all lie close to the surface make the blastoderm a natural target of investigators who want to understand how genes coordinate their expression on the way to forming a whole animal.

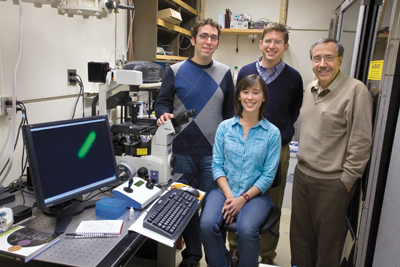

Members of the Berkeley Drosophila Transcription Network Project include (from left) Hanchuan Peng, Angela DePace, Oliver Rübel, Jitendra Malik, Charless Fawlkes, Mark Biggin, Mike Eisen, Soile Keränen, Bernd Hamman, Cris Luengo, Damir Sudar, Gunther Weber, and David Knowles. (Background shows visualization from BDTNP’s PointCloudXplore program.)

Members of the Berkeley Drosophila Transcription Network Project (BDTNP) at Berkeley Lab, UC Berkeley, and UC Davis have recently developed methods for looking at the Drosophila blastoderm in three dimensions, at the resolution of individual cells, while precisely measuring the expression of multiple genes as they interact to shape the fly.

“Visualizing gene expression and analyzing the morphology of an entire organism at cellular resolution has never been done before,” says David Knowles of the Berkeley Lab Life Sciences Division’s BioImaging Group. With the new methods the team detected surprising morphological and gene-expression features, overturning some long-held assumptions in the process.

3-D revelations at cellular resolution

A striking aspect of development during the blastoderm stage is the formation of “expression stripes” that encircle the embryo and move over its surface. The genes giving rise to these stripes control the later segmentation of the embryo.

Prior to the work of the BDTNP, biologists were limited to two-dimensional images taken at different stages from fixed embryos, no two of which were identical. Gene expression could not be assigned to specific nuclei from one image of a fixed embryo to the next, and the assumption arose that the movement of the blastoderm’s stripe patterns was due solely to gene expression. Nuclei didn’t need to move to produce moving stripes, because many of the genes’ expression products are transcription factors that regulate the expression of other genes.

The BDTNP collaborators also began with fixed embryos, but imaged them whole in three dimensions. “We set up a pipeline to make and compare thousands of high-resolution microscope images of different embryos at different stages of blastoderm development,” Knowles says. “For each image we stained the total DNA, which gives the location of each nucleus, plus we stained the expression patterns of two specific genes.”

By computer analysis these raw images, each some 500 megabytes in size, were converted into easy-to-manipulate text files called PointClouds. Each PointCloud records the center of mass of all blastoderm nuclei and the expression of two genes in and around each nucleus. By combining data from PointClouds, the researchers could estimate concentrations of many different gene products in each developing cell.

“We were able to populate our model with points that we could use to predict any possible nuclear movement,” says biologist Mark Biggin of the Genomics Division. “And we could separately measure the expression flow by tracking the collection of expressed genes. With the new model we could see the previously reported shift in gene expression stripes, but we also saw that the nuclei do in fact move — there is an intricate interplay between which genes are expressed and how the nuclei move.”

Methods to examine living embryos provide only partial, less precise measurements. Nevertheless, by following the development of living embryos during the blastoderm stage, the BDTNP team confirmed the model’s predictions.

The model produced other surprises. For one thing, says Knowles, “Expression of genes previously thought only to regulate development along the anterior-posterior axis“ — the head to tail axis — “also changes along the dorsal-ventral axis“ — the back to front axis. “As we go around the embryo in 3D, we see changes in expression along both axes.”

Future Directions

“When you have precision right down to the level of the cell, as we now do, all you have to do is ask a question and you’ll discover something,” Biggin says. “Our current study involves a limited number of genes acting in a small window of time. You just know you want this kind of information for the whole course of fly development, and for thousands of genes.”

Current PointCloud data can be downloaded from the Berkeley Drosophila Transcription Network Project website and used for research by any interested researcher. Grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, the National Human Genome Research Institute, and the Department of Energy‘s Office of Science funded the work.

For more information on gene expression in Drosophila, see the next edition of online Science@ Berkeley Lab.

Ergonomics Safety — Lab Adopts a More Proactive Approach

A woman in the Accelerator and Fusion Research Division recently received a new computer with a monitor that was five inches higher than her previous screen. Almost immediately, she began to experience discomfort in her neck.

Her initial reaction, which was to immediately seek ergonomics help, was correct. If employees believe they have an ergonomics problem, they should immediately contact their supervisor. If their supervisor is away, they should contact their Division’s Safety Coordinator, which is listed on the Lab’s EH&S homepage under the “who to call” navigation bar. The Division Safety Coordinator can help the supervisor and the employee address their unique problem with the correct resource.

Visit the Ergonomics Display Center in building 75B, room 110B, to try out furniture and accessories, or to review educational materials.

In this case, the woman was bending her head back to view the higher screen. Fortunately, she used a fully-adjustable table. Mike White, who recently joined the Lab’s Ergonomics Program with more than 20 years of ergonomics experience, lowered the rear display platform five inches and elevated the front input platform a few inches.

“She was sitting pretty with optimal head and neck viewing posture,” says White.

His work underscores a new way of creating an environment in which people work efficiently, safely, and comfortably. Today’s ergonomics is a systematic view of a person, their unique work style, and their work space. That’s the quick definition. The way it works in the real world is a bit more complex.

“A definition of ergonomics is looking at the fit between people, their jobs, and their workplaces,” says Ira Janowitz, who recently became the Lab’s Ergonomics Program Manager after 15 years with the UCSF/ Berkeley Ergonomics Program. “What we do next should be based on a problem-solving approach, not just following rules.”

As Janowitz explains, the computer has become much more interactive. It is no longer just data entry. “Today, people often lean back while they read their e-mail,” he says. “We need to tailor solutions to how people work, which is different from person to person.”

Based on this new approach, the Lab’s Ergonomics Program is unveiling a suite of tools designed to reach everyone. The Ergonomics Display Center in Building 75B, room 110B, is staffed full-time during business hours. Lab staff can drop by to try out furniture and accessories, and review educational materials such as videos, brochures, and posters. Employees with ergonomics questions are also encouraged to contact the Ergo Desk at x5818 or e-mail [email protected].

Ira Janowitz and Mike White

Janowitz and his team are also developing an ergonomics advocate program, which will train people in each Division on how to provide ergonomics support. “We are developing a collaborative network of people embedded in the Divisions,” explains Janowitz. The pilot training for this new program will be conducted in March. More than 20 people have expressed interest so far.

In addition, by the end of March, a pilot project featuring Remedy Interactive software, which allows employees to assess their own ergonomics risk factors using online tools, will be implemented in three divisions. This is part of an overall effort to give everyone at the Lab the skills they need to ensure a productive and safe work space.

“We want to help build employee self-reliance, and get their supervisor more involved,” says White. In fact, management accountability and employee self-reliance can help address the two biggest problems observed by Janowitz and White so far: improperly managing workload changes and not reporting ergonomics discomfort promptly.

Supervisors should help their staff evaluate and control risks when their workload increases, which is when routine work breaks become more important. Employees should realize the importance of breaks, and supervisors should include them in their employees’ work schedules. Supervisors should also be aware of how messages (verbal and non-verbal) are received by employees. Reminding an employee of a deadline six times a day, and never inquiring whether the employee is taking breaks or experiencing discomfort, sends the wrong message.

There is also well-documented evidence that seeking help when discomfort is first experienced increases a person’s chance of controlling the situation and averting a problem. The lesson is simple: people who experience discomfort should immediately request an ergonomics evaluation.

The Ergonomics Program also partners with the UCSF/UC Berkeley Ergonomics Program for advice and technical support. Debra Rosett assists the Joint Genome Institute with numerous ergonomics initiatives, and Kristin Amlie assists White and Janowitz with onsite discomfort evaluations at Berkeley Lab. These evaluations play a critical role in addressing ergonomics problems before they become injuries.

All of these tools are designed to give employees ergonomics solutions that take into account the human element, or how people really work.

“Ergonomics problems lead to more than discomfort, they also take their toll in wasted time and effort trying to react to situations that could have been prevented,” says Janowitz. “Berkeley Lab recognizes this and people are working hard to reduce risk and avoid injury.”

Berkeley Lab Science Roundup

Bright quantum rods

Carolyn Larabell, Paul Alivisatos, and Carolyn Bertozzi

Carolyn Larabell, Paul Alivisatos, and Carolyn Bertozzi

A team led by Paul Alivisatos and including Carolyn Bertozzi, Carolyn Larabell, Mark Le Gros, Weiwei Gu, Benjamin Boussert, and Daniele Gerion, from Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences, Physical Biosciences, Life Sciences, and Advanced Light Source divisions, and from UC Berkeley and UC San Francisco, have brought nanotechnology and biotechnology together to create fluorescing rod-shaped nanoscale semiconductors that are even better biological labels than their quantum-dot predecessors. In the Jan. 10 Nano Letters the researchers detail the performance of bright, linearly polarized, on-and-off switchable cadmium-compound nanorods, initially formed in organic solvents but adapted for biocompatibility. From five to 100 nanometers long, the nanorods are able to track single molecules and light up in different colors determined by their dimensions.

In search of twisted Martians

Richard Mathies of the Physical Biosciences Division and UC Berkeley joins scientists from NASA Ames, JPL, the Leiden Institute of Chemistry in the Netherlands, and other institutions who are attempting to determine whether Mars supports life now or ever did. The team, headed by Jeffrey Bada of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, is building the palm-sized Urey Mars and Organic Oxygen Detector. To be launched aboard the European Space Agency’s ExoMars spacecraft in 2013, the gadget will measure whether Martian amino acids twist left (as they do on Earth) or maybe right. Either way, if they all twist the same direction, they were likely formed in living things.

Catalyzing the catalysis in fuel cells

Vojislav Stamenkovic

Vojislav Stamenkovic

Keeping electricity markets honest

Charles Goldman

Charles Goldman

In case future electricity wholesalers should be tempted to imitate Enron and manipulate power markets in the western U.S. and Canada, they will first have to figure how to evade the watchful eye of the Western Interstate Energy Board (WIEB). Courtesy of DOE and the Environmental Energy Technologies Division’s Charles Goldman, WIEB has a new tool to monitor the price fluctuations of electricity in regional markets on a day-by-day basis and quickly identify outliers — that is, any seller whose price is, ahem, “anticompetitive.” Announced Jan. 29, the method is an application of econometric analysis and is described in a report titled A Regional Approach to Market Monitoring in the West, by Goldman and his colleagues from WIEB’s Analysis Group.

Metagenomics sucks in its gut

Derek Greenfield (left), Jessica Walter, Jan Liphardt, and Carlos Bustamante discovered how bacteria use the light-sensitive protein proteorhodopsin.

Derek Greenfield (left), Jessica Walter, Jan Liphardt, and Carlos Bustamante discovered how bacteria use the light-sensitive protein proteorhodopsin.

The Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute announced Jan.22 that it has updated the experimental metagenomics data management and analysis system known as Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG), initially developed by DOE JGI and Berkeley Lab’s Biological Data Management and Technology Center. Now called IMG/M, the system includes data from a battery of new microbial communities, including those found in the human distal gut, the guts of both lean and obese mice, a marine worm that has no gut at all, and, for good measure, biological sludge that removes phosphorus from wastewater, plus model reference genomes. The expanded IMG/M includes thousands of bacterial, archaeal, eukaryotic, and viral genomes.

Solar powered bugs

A decade ago a protein named proteorhodopsin was discovered in marine bacteria, which ought to have helped the bugs exist by photosynthesis. Yet when researchers shined a light on them, nothing happened. In the Feb. 2 edition of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Jan Liphardt, Jessica Walter, Derek Greenfield, and Carlos Bustamante of the Physical Biosciences Division report that proteorhodopsin isn’t useless after all; it does harvest sunlight, but only when the primary mechanisms of oxygen respiration are crippled. The researchers equipped E. coli with genes for the protein, impaired their ability to respire, and then reenergizing them by turning on the lights. Engineered bacteria able to harvest energy from more than one source could be efficient biofuel producers.

Catching Up With SNAP

A full-scale model of the SuperNova/Acceleration Probe’s Optical Bay was set up in the lobby of the Bldg 50 Auditorium during the annual meeting of the SNAP Collaboration held at Berkeley Lab Jan. 18-20. From left, Robin Lafever of the Engineering Division, who led the model construction; Samantha Edgington of Lockheed-Martin Space Systems, who gave an introductory talk to the assembled collaborators on how to turn science requirements into a set of practical mission requirements; Michael Levi and Saul Perlmutter, SNAP’s principal investigators, and George Smoot, present as a special SNAP “booster.” Nearly 140 members of the collaboration signed up for the three-day working session, which went forward in a mood of optimism despite budget uncertainties accompanying the start of the 110th Congress. Perlmutter’s opening-day news was that despite competing priorities at NASA, a National Academy of Sciences “Beyond Einstein Program Assessment Committee” will decide by September which of the Beyond Einstein cosmology programs sponsored by NSF, NASA, and DOE will be the first to launch. Should the Joint Dark Energy Mission (JDEM), of which SNAP is the leading contender, somehow be passed over, Congress has asked DOE and NASA to report progress on JDEM, with DOE ready to move ahead on its own if NASA has to drop out. In fact DOE has offered a $5 million grant to aid design optimization of Dark Energy experiments, for which the SNAP collaboration is competing; if they win, the grant would be used to build a prototype focal plane for SNAP’s revolutionary imager. Meanwhile SNAP’s design advances, closing in on final details.

Paul Alivisatos Becomes Lab’s 27th Lawrence Award Winner

Paul Alivisatos, director of the Materials Sciences Division for Berkeley Lab and Bock Professor of Nanotechnology at UC Berkeley, has been named one of eight new winners of the Ernest Orlando Lawrence Award by U.S. Department of Energy Secretary Samuel Bodman.

The Lawrence award, which is named for Berkeley Lab’s founder, the Nobel Prize-winning inventor of the cyclotron, is the highest scientific prize given by DOE. Alivisatos becomes Berkeley Lab’s 27th recipient of a Lawrence Award.

“I am very honored to receive this award since I have spent my whole career as a scientist supported in every way by the Lab Lawrence created,” Alivisatos said. “Through-out my career, I have been inspired by the spirit he imbued in this lab.”

Alivisatos, who also serves as Berkeley Lab’s Associate Laboratory Director for Physical Sciences, is widely recognized as the man who altered the budding nanoscience/ nanotechnology landscape with the creation of rod-shaped semiconductor nanocrystals that could be stacked to create nano-sized electronic devices. In addition to creating semiconductor nanocrystals of different shapes and sizes, and a new generation of hybrid solar cells that combine nanotechnology with plastic electronics, he has also helped launch several successful nanotech startup companies and mentored a growing body of highly successful young nanoresearchers.

Also winning a Lawrence Award in life sciences was Arup Chakraborty, a chemical engineer now at MIT. He did much of his award-winning research on T cells during the 17 years he was at Berkeley, where he held a joint appointment with Berkeley Lab’s Physical Biosciences and Materials Sciences Divisions, and both the Chemistry and Chemical Engineering Departments of UC Berkeley.

KQED QUEST Premiers on TV, Radio, Internet, and in Education

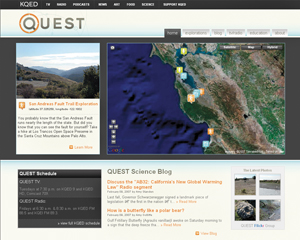

Earlier this month a unique initiative in science education began when KQED premiered its multiplatform series QUEST.

KQED's Quest homepage

KQED's Quest homepage

A weekly half-hour TV show, shot in high-definition TV, features two stories and runs at 7:30 p.m. on Tuesday, ahead of Nova, with repeats later in the week. The first episode included a CSI-like scientific mystery about brain lesions in sea otters which have caused a rising death rate and halted the recovery of the California otter population. While examining one corpse, wildlife pathologist Melissa Miller informed us that “autopsies” are performed only on ourselves, that is, humans; “necropsy” is the term for other species. Miller found that one cause of the otters’ lesions may be parasites in cat litter, improperly dumped into waters that drain into the ocean. The second segment of the premier dealt with a NASA mission to find water on the moon, during which team member Peter Schultz took great glee in blasting model craters in a NASA-sponsored sand box.

Berkeley Lab will be featured in “Nanoscience Takes Off,” the lead story on March 27. “From Lawrence Berkeley National Labs to Silicon Valley, researchers are manipulating particles at the atomic level,“ reads the blurb, “ushering in potential cures for cancer, clothes that don’t stain, and solar panels as thick as a sheet of paper.“ Among those interviewed from the Lab are Paul Alivisatos, Alex Zettl, Frantisek Svec, and their nanoscientific colleagues.

The Lab also features in the first group of radio stories, which air on Fridays at 6:30 and 8:30 a.m. (with later repeats), with a story on Heat Islands and cool roofs featuring Lab scientist Hashem Akbari. The radio stories are ambitious and well-told (the first was on the current availability of biodiesel in California), and constitute unusually thorough reporting for radio news.

Berkeley Lab also contributes to QUEST’s interactive website, with Jim Gunshinan, a guest in EETD, and Kyle Dawson, a postdoc in Physics, signed up for weekly postings on the site’s science blog. Other web features include the ability to replay the TV and radio shows in excellent fidelity, links to educational activities for grades K through 12, maps and guides for local explorations, a gallery of related photos, links to QUEST’s “partners” (Berkeley Lab has been a partner since the show was in development), and other ways to magnify the learning experience.

All in all, KQED QUEST has made an auspicious start in its ambitious approach to science education.

People, Awards, and Honors

Life Scientist to Lead Mutagen Society Berkeley Lab life scientist Priscilla Cooper was selected as President-elect of the Environmental Mutagen Society. Cooper, an expert on molecular mechanisms of DNA repair in humans and head of the Genome Stability Department in Life Sciences, will assume this role in October. The society provides a forum for more than 750 active members from around the world who are interested in the effect of chemicals and agents that affect the genome of humans and animals and the application of this knowledge in genetic toxicology.

Earth Scientists Win $4.5 Million in Awards

Six investigators in the Environmental Remediation Program of Berkeley Lab’s Earth Sciences Division were recently successful in securing over $4.5 million in funding from DOE’s Environmental Remediation Sciences Program for projects that will be carried out over the next three to five years. Successful project-based proposals include those of Jiamin Wan, Mark Conrad and Terry Hazen; successful field research center proposals were approved for Don DePaolo, Ken Williams and Susan Hubbard. They all focus on the use of advanced geophysical, geochemical, microbiological, and hydrological approaches for understanding complex subsurface phenomena.

Appointments, Fellowship For Computing Scientists

Three employees with the Lab’s Computational Research Division (CRD) have recently received recognition by scientific organizations. Vern Paxson (left), with the Distributed Systems Department, was named a fellow of the Association of Computing Machinery. Horst Simon (center), CRD director, was named to the DOE’s Advanced Scientific Computing Advisory Committee. Juan Meza, head of CRD’s High Performance Computing Research Department, will serve on the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics’s committee on science policy, and was also elected to a three-year term on the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s “Electorate Nominating Committee of the Section of Mathematics.”

Computational Scientist Elected Chair of SIAM Group

John Bell, head of the Center for Computational Sciences and Engineering, has been elected chair of the SIAM Activity Group on Computational Science and Engineering (CS&E). SIAM is the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. The activity group “fosters collaboration and interaction among applied mathematicians, computer scientists, domain scientists and engineers in those areas of research related to the theory, development, and use of computational technologies for the solution of important problems in science and engineering.” Bell’s two-year term ends in December 2008. With more than 1,200 members, the CS&E group is the largest of SIAM’s 15 activity groups.

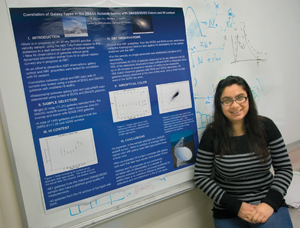

Physics Undergrads Win Chambliss Awards at AAS

At the American Astronomical Association’s meeting in January, Ferah Munshi (left) won the Chambliss Student Achievement Award medal for her poster presentation reporting work correlating the hydrogen content and color of galaxies with their types. Munshi is a UC Berkeley undergraduate in the Physics Division, as are Chambliss honorable mention awardees Mark Wagner (below left) and Tyler Pritchard, whose poster reported a calculation of the actual brightness of three supernovae magnified by gravitational lensing.